Executive Summary

Nei rā ka tau mai rā te ao hurihuri nei; he hau mai tawhiti, he tohu raukura nā ngā tīpuna. Inā Te Tiriti o Waitangi tonu! He tauira, kōkiritia te kaupapa nei! Rau rangatira mā. Nāu! Nāku! Kia ora ai tātou. Tēnā koutou. Tēnā tātou! Kia ora tātou katoa!

As the changing world swirls about us, we muster wisdoms from our pasts to help, helping us to forge ahead in a new world. Bearing the raukura plume of our forebears, and the dignity of Te Tiriti o Waitangi, we can address, grapple with, and overcome this challenge!

Greetings all! We invite you to contribute and to participate - knowing that from everyone's efforts, new paths are found. Our greetings, and our acknowledgments to all.

Kia ora tatou katoa!

The tax system matters to everybody

Few areas of public policy contribute as much to the welfare of New Zealanders as taxation. Taxes allow the Government to fund the vital public services - such as healthcare, education, justice, expenditure on healthy ecosystems, and defence - that underpin our living standards.

The calculation and payment of tax also imposes obligations on New Zealanders and the tax system affects different groups of people in different ways. As a consequence, tax is not just for ‘experts' - all New Zealanders have a stake in the design of our tax system.

About the Tax Working Group

The Government has established the Tax Working Group (the Group) to examine further improvements to the structure, fairness, and balance of the tax system. The Group has also been directed to apply a particular focus on the future to its work, with a view to exploring the major challenges, risks, and opportunities facing the tax system over the next decade and beyond.

We want to hear your views

This paper calls for public submissions on a range of issues that the Group considers important to its work. Public submissions will inform the Group's consideration of proposals for improving the tax system.

The Group will provide an interim report on these proposals to the Ministers of Finance and Revenue in September 2018. There will be further opportunities for public comment following the publication of that interim report.

In the spirit of openness and inclusion, the Group would now like to encourage all New Zealanders to share their own views about what is working - and what is not - in the current tax system.

Challenges, risks, and opportunities

Tax systems have always had to evolve alongside changing practices in business, technology, and society. However, technology today - particularly in the area of digital communications - is having a radical impact on the way businesses operate, both within and across national borders.

Within this context, the Group has identified eight broad challenges, risks, and opportunities that will affect the tax system over the coming decade and beyond:

- changing demographics, particularly the aging population and the fiscal pressures that will bring;

- te ao Māori and the role of the Māori economy in lifting New Zealand's overall living standards;

- the changing nature of work;

- technological change and the different business models that will bring;

- falling company tax rates around the world;

- environmental challenges, including climate change and loss of ecosystem services and species;

- growing concern about inequality; and

- the impacts of globalisation and changes in its patterns.

Our tax system will need to be sufficiently robust to deal with these challenges, and sufficiently nimble to take advantage of the opportunities. There will also be other shocks and surprises that we have not considered and cannot foresee.

The Group would therefore like to hear your views on how these challenges and opportunities might affect the tax system, and, equally importantly, whether you consider there are any other key issues that policymakers will need to prepare for.

The purposes and principles of a good tax system

Even as the tax system evolves in response to these risks and opportunities, it will still need to fulfil the central purpose of tax policy: to provide sufficient revenue to the Government to fund the provision of public goods, services and transfers.

But the design of the tax system will also have broader impacts on the wellbeing of New Zealanders across the social, economic, and environmental dimensions. The Group intends to be mindful of these impacts as it develops recommendations for reform.

In recognition of the broad basis of wellbeing, the Treasury uses the Living Standards Framework to incorporate a more comprehensive range of factors into its analysis. The Living Standards Framework identifies four ‘capital stocks' that are crucial to intergenerational wellbeing:

- Financial and physical capital, such as roads, factories, and financial assets.

- Human capital, such as skills and knowledge.

- Social capital, such as trust, cultural achievements and community connections.

- Natural capital, such as soil and water.

The Living Standards Framework encourages us to consider how policy change is likely to impact each of the four capitals, and broadens our assessment beyond strictly economic considerations.

The established criteria that have been used in past tax reviews (both domestically and overseas) are also useful when considering the costs and benefits of various reforms:

- Efficiency: minimise impediments to economic growth and avoid distortions (biases) to the use of resources.

- Equity and fairness: achieve fairness including through ‘horizontal equity' (the same treatment for people in the same circumstances) and ‘vertical equity' (higher tax obligations on those with greater economic capacity to pay). Procedural fairness is also important for a tax system.

- Revenue integrity: minimise opportunities for tax avoidance and arbitrage.

- Fiscal adequacy: raise sufficient revenue for the Government's requirements.

- Compliance and administration costs: minimise the costs of compliance and administration, and give taxpayers as much certainty as possible.

- Coherence: ensure that individual reform options make sense in the context of the entire tax system.

As you read this paper, the Group would encourage you to consider which principles and frameworks are most important to you in evaluating the tax system, and to test your own ideas and proposals against them.

The design of the current tax system

New Zealand currently has a ‘broad-based, low-rate' tax system. The Government raises about 90% of its tax revenue from three tax bases:[1]

- Individual income tax

- Goods and services tax (GST)

- Company income tax.

There are very few exemptions to these three taxes (which is why our tax system is described as ‘broad-based'). The benefit of having a broad base is that it allows the Government to raise substantial revenue with relatively low rates of taxation. Overall, the current level of tax revenue, including local government rates, is equivalent to 32% of gross domestic product (GDP), which is slightly below the OECD average of 34% of GDP.

New Zealand's tax system is distinct in other ways. Unlike many other countries, New Zealand does not generally use the tax system to deliberately modify behaviour - with the notable exceptions of alcohol and tobacco excise taxes, which are intended to discourage drinking and smoking.

New Zealand's approach to the taxation of retirement savings is also distinct. The tax system does not offer large concessions for retirement savings; retirement savings contributions are taxed when they are made and as investment income is earned, rather than when the savings are drawn down in retirement.

The Group's work provides an opportunity to examine whether a broad-based, low rate system remains fit-for-purpose, and whether there is a case to depart from the internationally distinctive approaches to behavioural taxes and retirement savings. It is also an opportunity to explore whether there is a case to broaden the base further, for example with new taxes such as a comprehensive capital gains tax (excluding the family home).

The results of the current tax system

Revenue outcomes

New Zealand's broad-based, low-rate system succeeds at raising relatively high amounts of revenue with relatively low rates. Compared with other OECD countries:

- New Zealand has one of the lowest top personal tax rates, but the proportion of income tax to GDP is high.

- New Zealand's company tax rate is relatively high, and the proportion of company tax revenue to GDP is high.

- New Zealand's GST rate is relatively low, but the proportion of GST revenue to GDP is high.

New Zealand's GST is one of the simplest and most comprehensive in the world. There are two main exemptions - for financial services, and for low-value imported goods.[2] These exemptions reflect past judgements that it would be too administratively complex to include financial services and low-value imported goods in the tax.

Distributional outcomes

Higher-income households play an important role in funding the Government. According to established income measures, the share of all income tax paid increases as household income increases. Households in the top income decile (that is, the 10% of households with the highest incomes) pay around 35% of all income tax, whereas households in the lowest five income deciles (that is, 50% of households) collectively pay less than 20% of all income tax.

The tax and transfer system (transfers are payments like Jobseeker Support and New Zealand Superannuation) reduces income inequality, although by less than most of our comparator countries. New Zealand's tax and transfer system provides a similar reduction in measured income inequality to the Canadian system, but a smaller reduction than Australia or the OECD average.

Income inequality in New Zealand rose rapidly in the late 1980s to mid 1990s, but has been broadly stable in New Zealand since then. Information about wealth is less comprehensive than for income, but the information we do have indicates that wealth is distributed much less equally than income.

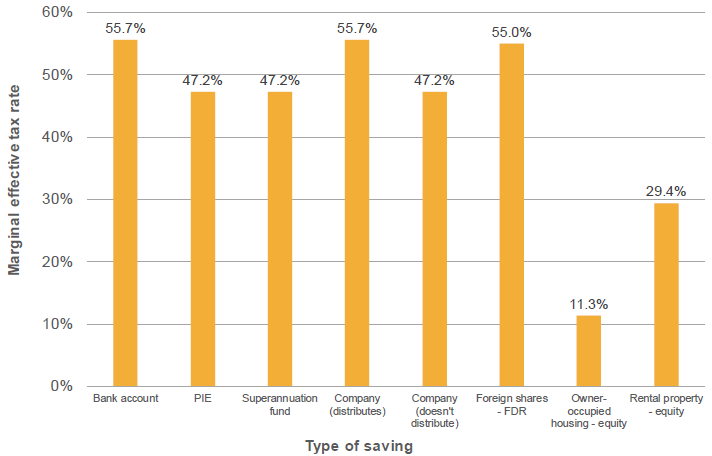

Savings

There is some debate about the influence of our tax settings on the rate and composition of saving in New Zealand. In a broad-based, low-rate tax system, there should ideally be no difference in marginal effective tax rates between different types of investments. Relative to other countries, New Zealand's marginal effective tax rates are quite uniform, but it may be possible to achieve more consistency in the treatment of different types of investments.

Overall outcomes

The Group is keen to hear public views on the overall performance of the tax system, and has a particular interest in assessments of the fairness and balance of our tax settings.

Thinking outside the current system

New Zealand has reduced its use of other tax bases under the broad-based, low-rate tax system. Previous reforms have eliminated the sales tax, excess retention tax, land tax, estate duty, stamp duty, gift duty and cheque duty. New Zealand also does not levy financial transaction taxes, wealth taxes, or a general capital gains tax. The Group will examine whether there is a case to introduce any additional taxes, particularly in light of growing international debate about income and wealth inequality.

The Group also acknowledges public concerns about the tax practices of some multinational corporations, which exploit inconsistencies and mismatches in domestic tax rules in order pay little or no tax anywhere in the world. In this regard, New Zealand is currently implementing a suite of measures - developed in cooperation with other OECD countries - that will further strengthen the rules for taxing income from investment in New Zealand.

But we also need to consider the taxation of income from the digital economy. Internet-based firms can trade with customers over the internet without having a physical presence in the customer's country that is necessary for income tax to be charged under present rules. This issue is becoming increasingly important as the digital economy accounts for a greater proportion of business activity.

The Group invites comment on what the public sees as the most significant inconsistencies in the current tax system, and which of these should be addressed most urgently.

Specific challenges

In addition to the issues discussed above, the Government has directed the Group to advise on a number of specific challenges:

- How would a capital gains tax (excluding the family home) or a land tax (excluding the land under the family home) affect housing affordability, and would these taxes improve the current system for capital income taxation? Relevant considerations will include: the impacts of these taxes on property-owners and renters; the ease of administering these taxes; the interaction of these taxes with the rest of the tax system; the extent to which the tax will incentivise productive investment as opposed to speculation; and the possibility of allowing for reductions in other taxes as a result of introducing them.

- Is there a case to introduce a progressive company tax (i.e. lower company tax rates for smaller businesses) in order to support small business?

- Is there a case to make greater use of environmental taxation to improve environmental outcomes and diversify the tax base?

- Could the Government assist low-income people by introducing GST exemptions for certain goods and services?

The Group seeks public views on all of these matters. It also invites submissions on the question of which taxes should be lowered if new sources of tax revenue can be found (keeping in mind the guidance in the Terms of Reference for tax revenue to remain at approximately 30% of GDP).

Concluding thoughts

New Zealand's tax system has many strengths, but it cannot stand still. We are living in an era of rapid technological change, rising economic uncertainty, and mounting environmental challenges. Our tax system must be robust to these challenges, even as it takes advantage of the administrative and other opportunities afforded by innovation.

However, it is important that we maintain the trust and confidence of all New Zealanders in the integrity of the tax system. In a democracy such as ours, the ability of the Government to raise revenue rests ultimately on the consent and acceptance of all New Zealanders.

In order to maintain this acceptance, and fulfil the trust of New Zealanders, we must ensure that the tax system is fair, balanced, and administered well. This is the goal the Group is working towards. Your submissions will help us achieve it.

1 Introduction

The Tax Working Group (the Group) has been established by the Government in order to examine improvements in the structure, fairness, and balance of the tax system.

This paper is a call for public submissions on a range of issues that the Group thinks are important for the purpose of carrying out its work. Specific questions that we are particularly interested in your views on are contained throughout the paper at the beginning of each chapter. Submitters may submit on other issues, but should be aware of the exclusions in the Terms of Reference. The Terms of Reference are attached as an appendix to this paper.

To help submitters, this paper also provides information and context on New Zealand's current tax system and tax concepts. Terms that are italicised are explained in more detail in the glossary.

Process

The Group is chaired by Hon Sir Michael Cullen and is supported by a secretariat of officials from the Treasury and Inland Revenue. The Chair has appointed an independent advisor to assist the Group with its deliberations and understanding of the issues.

The Group held its first meeting in January 2018 and will continue to meet regularly until February 2019, when the Group's final report to the Minister of Finance and the Minister of Revenue will likely be issued. The indicative timeline for the Group's work also includes an interim report to the Minister of Finance and Minister of Revenue in September 2018. There will be a further opportunity for public submissions on the Group's proposals contained in the interim report following its publication.

Submissions

The Group seeks submissions on the issues set out in this paper. In particular, the Group is interested in solutions to problems that the Group, or submitters, have identified.

Submissions should include a brief summary of major points and recommendations. They should also indicate whether it would be acceptable for the Group and the secretariat to contact those making the submission to discuss the points raised, if required.

Submissions should be made by 30 April 2018 and can be emailed to submissions@taxworkinggroup.govt.nz or submitted online at https://taxworkinggroup.govt.nz

Alternatively, submissions may be addressed to:

Tax Working Group Secretariat

PO Box 3724

Wellington 6140

New Zealand

Submissions will be proactively released and only redacted or withheld on the grounds of privacy, commercial sensitivity, or any other reason under the Official Information Act. Those making a submission who consider that there is any part of it that should properly be withheld under the Act should clearly indicate this.

In addition to seeking written submissions, the Group intends to discuss the issues raised in this paper with key interested parties.

2 The future environment

- What do you see as the main risks, challenges, and opportunities for the tax system over the medium- to long-term? Which of these are most important?

- How should the tax system change in response to the risks, challenges, and opportunities you have identified?

- How could tikanga Māori (in particular manaakitanga, whanaungatanga, and kaitiakitanga) help create a more future-focussed tax system?

Predicting the future is inherently difficult. We want to make sure we are taking into account the most important changes and, with that in mind, we describe some below. We also want your ideas and welcome submissions on challenges and opportunities that we have missed. Future challenges and opportunities that we believe could affect New Zealand include:

- changing demographics, particularly the aging population and the fiscal pressures that will bring;

- te ao Māori and the role of the Māori economy in lifting New Zealand's overall living standards;

- the changing nature of work;

- technological change and the different business models that will bring;

- falling company tax rates around the world;

- environmental challenges, including climate change and loss of ecosystem services and species;

- growing concern about inequality; and

- the impacts of globalisation and changes in its patterns.

Along with challenges there will be opportunities. Technology will undoubtedly provide new and low-cost ways of collecting tax information and tax revenue and monitoring compliance. Initiatives in the tax system could assist in achieving other, broader outcomes, such as improving fairness or responding to environmental concerns.

Changing demographics - the aging population and fiscal pressures

Like much of the developed world, New Zealand has an aging population. In He Tirohanga Mokopuna - the latest statement on New Zealand's long-term fiscal position - the Treasury describes the fiscal consequences of an aging population as:[3]

- slower revenue growth from lower labour force participation, and

- increased expenses, largely due to higher spending on healthcare and New Zealand Superannuation.

It is also important to note other demographic changes. The ratio of people aged 65 and over as a proportion of people aged 15-64 is projected to more than double, from 23 percent in 2016 to 50 percent in 2068.[4] At the same time, projections suggest that Māori, Pacific and Asian populations will continue to have a much younger age structure than the total New Zealand population. These groups are not only younger; they are growing faster than the overall New Zealand population, and will play an increasingly important role in our economic future. However, if the educational, employment and income outcomes of Māori and Pacific groups remain behind the total population, this transition carries risk.

The Government's fiscal objective for the tax system is to support a sustainable revenue base to fund government operating expenditure around its historical level of 30 percent of gross domestic product (GDP). If the Government is to continue providing healthcare and superannuation at current levels, then the level of taxation will need to increase, or spending on other transfers or publicly provided goods and services will need to fall.

Table 1 illustrates the timing and magnitude of the issue.

| 2015 | 2030 | 2045 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary expenses | 28.4 | 31.1 | 33.8 |

| Primary revenue | 28.9 | 29.8 | 29.8 |

| Primary balance | 0.5 | (1.2) | (4.0) |

Projections like those in Table 1 raise intergenerational equity issues if one generation considers it is required to make an unreasonable contribution to superannuation and health costs relative to the benefits it receives. The same occurs when governments operate continuously in deficit; today's deficits need to be funded by tomorrow's taxes.

The current tax system will face changes of its own due to the aging population, even if spending requirements do not increase. The tax mix will change. Taxes on capital income (for example, interest on term deposits, dividends, etc.) and consumption (for example, goods and services tax (GST)) may become relatively more important and taxes on labour income relatively less important as a source of future revenue, if the proportion of those earning capital income relative to labour income increases. Over time it is likely that a focus on capital income taxation will be increasingly important in ensuring that the tax system is as fair and efficient as possible.

The flexibility of the tax system is important for the future. At the same time certainty - the ability to signpost the desired direction of tax policy and avoid unexpected policy shocks - is also important.

Te ao Māori and the future

Māori economic development will be a key driver of improved living standards in Aotearoa New Zealand

Māori - as employees, owners, governors, managers or kaumātua - are the cornerstone of Māori economic development.

Māori economic development can be characterised in two parts: ‘the Māori economy' and ‘Māori in the economy'. ‘Māori in the economy' refers to people identifying as Māori participating in the economy. This happens in many ways (for example, as taxpayers, business owners, entrepreneurs and consumers).

The ‘Māori economy' refers to a spectrum of business activities - from small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) directly lifting the living standards of individuals and whānau, to purpose-driven collective businesses and asset holding companies reinvesting in hapū and iwi. The Māori economy also includes capital stock that is specifically identified as Māori (e.g. Māori freehold land, Iwi assets and Māori businesses).

The Māori economy is growing and there is potential for further growth. Between 2010 and 2017, the Māori asset base grew from an estimated $36.9 billion to approximately $50 billion.[6],[7] Māori also have a thriving entrepreneurial base. With approximately 8,500 Māori-owned SMEs and a further 21,000 Māori classified as self-employed, Māori SMEs will continue to add to a growing asset base.[8]

The growth of the Māori economy can be characterised by a strong focus on intergenerational sustainability, diversification, and tikanga Māori. Values such as manaakitanga (the care of land and each other), whanaungatanga (wider kindship ties) and kaitiakitanga (guardianship and sustainability) drive business, investment and distribution decisions.

While the promise of the Māori economy continues to grow, disparities persist between Māori and other New Zealanders

The Māori unemployment rate of nine percent is double that of the national unemployment rate.[9] In addition, over a quarter of working-age Māori adults and their whānau receive a benefit, whereas the national rate sits at approximately 10 percent.[10]

These disparities also appear in the context of housing in Aotearoa New Zealand. Forty-four percent of people on the Social Housing Register[11] (that is, people assessed as being eligible for public housing) are Māori. Fifty-seven percent of emergency housing grants are required by Māori.[12]

We want to hear from Māori

The Group is interested in hearing from Māori on a range of issues.

All Māori individuals, companies and trusts under which Māori benefit are subject to the tax system, and Māori will have a number of cross-cutting interests in issues on the Group's agenda. This includes issues like housing, capital gains tax (CGT), charities and land taxes covered elsewhere in this paper.

However, with changing demographics and the growing role of the Māori economy, we also encourage submissions on:

- Whether the Māori authority tax regime supports or hinders Māori economic and social development.

- Whether there are parts of the current tax system that warrant review from the point of view of te ao Māori

- How tikanga Māori might be able to help create a more future-focused tax system.

The changing nature of work

The gig economy generally refers to workers who have less regularity in their sources of income, working hours and conditions, and often operate as independent contractors.

Our pay-as-you-earn (PAYE) system currently provides a highly efficient way of collecting revenue, which is easy to comply with and has relatively low administration costs. However, if self-employment rates increase in the future, this could put pressure on the PAYE system and affect compliance rates. In particular, growth in the ‘gig economy' may mean that changes need to be made to the way that independent contractors pay their tax to ensure that compliance remains high and that the cost of complying with tax for these workers is low.

It is not just technological change that is driving the changing nature of work. Patterns of globalisation and the aging population (both discussed elsewhere) also intersect with the way we work and will require adjustments.

Labour adjustments are not always easy, particularly for people who are already experiencing economic hardship. While the gig economy can bring more flexibility for some workers, it can also increase economic insecurity for other New Zealanders, leading to an increased sense of precariousness and vulnerability. This emphasises the importance of accessible and effective social services, resilient families and whānau, and the wider need for the tax and transfer system to work effectively.

In addition, labour is becoming more internationally mobile. As a result it is likely that it will become more common for people to be working for short periods in New Zealand, and for New Zealanders to be working for short periods abroad. It is important that the tax system minimises double taxation while ensuring that double non-taxation does not occur.

Technological change and its impact on tax bases

The internet will continue to change the way that businesses operate. Tax systems have always had to evolve with evolutionary changes in business practices and technology. However, recent changes in technology, particularly with digital communications, are changing business practices and the way people earn income.

The traditional company tax model was created in a very different economy. Services can now be supplied into New Zealand by businesses that do not have any physical presence here, which limits New Zealand's ability to tax those businesses.

There is rapid growth in the sharing economy.[13] The sharing economy generally refers to people using online platforms to share assets such as their house or car with third parties. It is now common for people to rent out their homes (or part of their homes) for short periods of time. As this becomes a larger part of the economy, the amount of income that might not be subject to third-party withholding or reporting regimes will increase. This raises the question of how to ensure that tax compliance overall remains high.

Technological advancements in transport may affect the traditional base of fuel excise duty as vehicles become more fuel efficient. Blockchain technologies and the use of cryptocurrencies may allow sizable transactions to be made without using traditional intermediaries. This could undermine third-party reporting and withholding of tax. Encryption hides the transaction and may remove information that can be used in audits.

There are other, more speculative arguments that the future will bring great disruption to the returns to labour and capital. While technological advancement has historically resulted in both job destruction and creation, some commentators question whether the coming wave of technological change will actually create jobs. If material overall job destruction occurs, then the implications for society would be far wider than the implications on the tax system. However, we might expect the tax revenue from labour taxation to fall. It is possible that there will also be a permanently larger number of people who are persistently under-employed, and this could put pressure on the transfer system (for example, transfer payments such as Working for Families tax credits and Jobseeker Support).

At the same time, if business costs reduce as a result of technological change, company taxes should raise additional revenue from greater profits to the extent that those companies remained in the New Zealand tax base. There is and will be uncertainty and disagreement about what direction New Zealand and the world are headed, but New Zealand must have a tax system flexible enough to gather revenue to fund government services and transfers.

Opportunities for tax administration and policy from technological change

The shift to digital technology and greater globalisation has reshaped how businesses and individuals interact and connect, as well as their expectations of government. A modern, digital revenue system needs to serve the needs of all New Zealanders. Inland Revenue's Business Transformation programme aims to help people get their tax and social policy payments right from the start, avoid errors, and give them a clearer view of what they have paid and what they owe during the year. This creates new opportunities to help people spend far less time and effort ensuring they have met their obligations and received their correct entitlements, as tax will be withheld correctly and assistance provided at the time it is needed.

It is intended that in the future Business Transformation will provide opportunities to make wider tax system changes. As an example, one area that is likely to grow in importance is the treatment of data held by the tax administration as Inland Revenue looks to improve the value of information it holds and make greater use of it.

Another example is the recently enacted Accounting Income Method for paying provisional tax. This has been an opportunity for the efficient administration of existing tax bases, created by the increased use of cloud accounting systems. The tax system must be able to seize these opportunities.

Company tax pressures

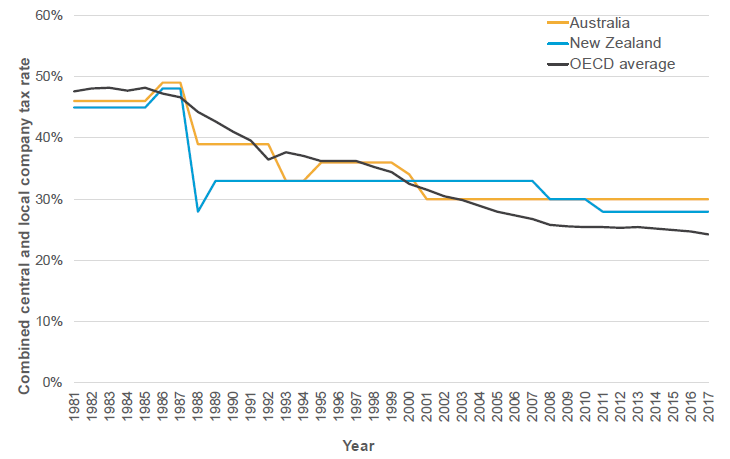

At 28%, New Zealand's company tax rate is relatively high. For domestic shareholders, New Zealand's imputation regime means that the final tax rate on investments in companies is normally taxed at the shareholder's marginal tax rate.[14] When factoring in imputation, New Zealand's tax rate on domestic shareholders is the sixth lowest in the OECD. Foreign shareholders do not receive imputation credits and for them it is the company rate that is relevant. As at 2017 New Zealand's company rate is the tenth highest in the OECD, with the unweighted OECD average being 24.9%. Figure 1 compares historic company tax rates for New Zealand, Australia and the OECD average.[15]

- Figure 1: Historical trends in statutory company tax rates

Source: OECD

Source: OECD

New Zealand has reduced its rate in recent years (in 2007 it was 33%), but other OECD countries have reduced their rates by a greater margin than New Zealand, resulting in New Zealand climbing up the OECD rankings of corporate tax rates. As noted in Chapter 7, Australia has a (temporarily) lower tax rate for smaller firms.

It is in New Zealand's best interests to set its corporate tax rate according to its own circumstances and constraints; it is not simply a matter of trying to have a tax rate that is lower than the rest of the world or our immediate neighbours.

The top personal tax rate, and the rate for trusts, is 33%. The 5% rate differential between the company and personal tax rates encourages what are referred to as tax sheltering arrangements. There is a risk of tax sheltering when the company tax rate is significantly lower than the top personal rate. By world standards, New Zealand has a relatively small gap between its company rate and its top personal rate but New Zealand has experienced significant tax sheltering in the past and has relied on a high degree of alignment with relatively few protections against this form of sheltering. Additional protections would need to be considered to support a larger difference between company and personal rates if such a difference comes about in the future.

New Zealand must be aware of the international environment and future governments should have the option of reducing the company tax rate if this is considered sensible without the possibility of greater personal tax sheltering being an overwhelming obstacle.

Environmental challenges

Climate change is having, and will continue to have, significant impacts on people, the environment, and the economy. New Zealand has committed to reducing net emissions by 30 percent below 2005 levels by 2030, and the Government has announced that it will develop a new emissions target for 2050. Due to the proportion of emissions that come from the agriculture sector, where emissions-reduction options are limited, New Zealand may face higher costs than other countries to meet its targets.

Using the tax system to ensure that consumers and producers face the costs of emissions and other environmental harm could be one way we can meet our international obligations and encourage innovative ways to reduce pollution. The Government has recently announced the creation of an independent Climate Change Commission. Although still being established, the Commission is expected to advise the Government on climate policy including changes to how we price carbon. The treatment of agricultural emissions, which are currently excluded from New Zealand's Emissions Trading Scheme, has been flagged as an initial area of focus for the Commission.

Environmental challenges extend well beyond climate. New Zealand is a biodiversity hotspot, and the unique species and ecosystems make up the country's natural capital. New Zealanders' wellbeing is closely linked to the ecosystem services that natural capital provides. Indigenous biodiversity has rapidly declined and continues to be threatened, especially on private land. New Zealand now has one of the highest proportion of native species at risk, and in a review of 71 rare ecosystems in New Zealand 45 species were found to be threatened with extinction.[16] It is possible for pricing and tax instruments to play a role in addressing these challenges. Government responses to such challenges have also included targeted regulations aimed at discouraging unwanted behaviours. As well as being valuable in its own right, the natural environment supports tourism - a significant part of New Zealand's economy.

Concern about inequality

The New Zealand public, like the public in many countries, is concerned about inequality. The tax system can play a major role in combatting inequality both through taxing people with higher incomes at higher rates, and through redistribution and spending. It will be important that New Zealand's tax system can play that role now and in the future.

Tax systems can be thought to affect inequality through three dimensions: the progressivity of taxes, the overall level of taxation, and the mix of taxes. As progressivity of taxes increases, and overall levels of taxation increase, inequality falls. The mix of taxes is important because some taxes are likely to be more or less progressive than other taxes.

Changing patterns of globalisation

Globalisation has allowed New Zealanders to engage internationally in an unprecedented way. The array of products and services available to New Zealanders and the opportunities to produce for a global market are greater than they have ever been. At the same time, changing patterns of production and employment can impose significant costs on local communities.

In the tax context, the shifting of economic activity that was previously located in New Zealand limits New Zealand's ability to tax those firms under the traditional model for taxing cross-border investment.

Looking to the future, it is an open question as to the direction of globalisation. Recent events (for example, “Brexit” - the majority vote in the UK referendum to leave the European Union) might suggest that in some countries globalisation may retreat.

We must have a tax system that meets our revenue needs while not unduly restricting our ability to engage with the rest of the world.

3 Purposes and principles of a good tax system

- What principles would you use to assess the performance of the tax system?

- How would you define ‘fairness' in the context of the tax system? What would a fair tax system look like?

What are taxes?

The primary objective of tax policy is to provide revenue for the government to fund the provision of public goods and services, and redistribution. Oliver Wendell Holmes put it more succinctly: “Taxes are what we pay for civilized society”.[17] Increasingly there are other objectives for tax systems: for example, to influence behaviours, or encourage sustainability.

Public goods and services provided to its residents by the New Zealand Government include healthcare, education, policing, and defence. Transfers are payments to residents who might be on low incomes, or who live in hardship, or meet some other criteria like having young families. The Government raises the revenue for the public goods and services and transfer payments from a number of sources. Some services provided have a direct charge (for example, renting DOC hut space on tramping tracks). Some revenue is raised from imposing fines in order to discourage unwanted behaviour (for example, speeding fines). However, by far the largest source of revenue is taxation, which is a legal requirement imposed on individuals and entities (such as companies and trusts) to pay some amount of money to the government (without any direct connection with the supply of goods or services).

There are some things that a government is best placed to do. A justice system, parliamentary democracy, social support entitlements, public health, public education, roads, natural disaster relief, standard setting, regulation, national parks, protection of ecosystems and species conservation are all examples of expenditure that create a modern, compassionate, and prosperous society. These are goods and services where provision by the government can ensure that society is made better off. We may debate the extent of these examples, but few would doubt the need to provide them.

Taxes also fund a safety net that maintains a minimum standard of living. In this way, taxes could be seen as a payment for a kind of social insurance that mitigates the impact of unexpected economic shocks with the intention that everyone regardless of income can participate in society.

- Figure 2: Tax as a proportion of GDP and GDP per capita (USD ) in OECD countries (2015)

Source: OECD

Source: OECD

Few areas of public policy can contribute as much to New Zealand's welfare as a well-performing tax system. Tax is half the story when considering the Government's overall budget and roughly equivalent to one-third of New Zealand's GDP. A well-performing tax system ensures that society can fund the things it cares about, while ensuring that households and businesses have appropriate incentives to work, save, innovate and invest.

As illustrated in Figure 2, high-income countries have a variety of tax levels relative to GDP, and it is generally the lower-income countries that have the lowest tax-to-GDP ratios. This may be because as incomes increase, countries choose to spend a greater proportion of national income on transfer payments and publicly provided goods and services.

Taxes and wellbeing

The ultimate purpose of public policy is to improve the wellbeing and living standards of New Zealanders. Many factors affect New Zealanders' living standards, and many of these factors have value beyond their contribution to material comfort. Aggregate national income, or GDP, is an important enabler of higher living standards - not least because of its direct connection to the tax base - but it is not designed to be a measure of wellbeing.

To measure wellbeing comprehensively, income measures therefore need to be supplemented with measures of other factors, such as health, connectedness, security, rights and capabilities, inequality, and sustainability.

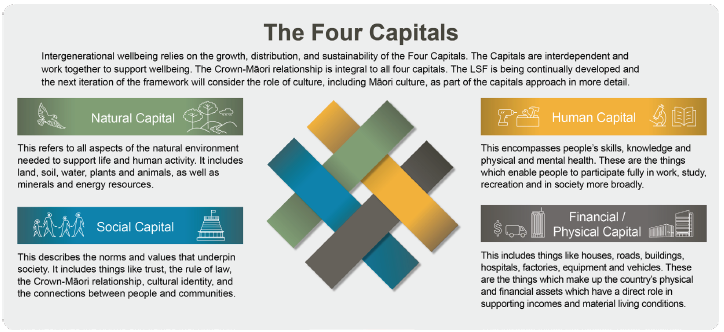

In recognition of the broad basis of wellbeing, the Treasury uses the Living Standards Framework to incorporate a more comprehensive range of factors, distributional perspectives, and dynamic considerations into its analysis. The Living Standards Framework identifies four capital stocks that are crucial to intergenerational wellbeing: financial and physical capital; human capital; social capital; and natural capital.

The Treasury represents the ‘four capitals' visually as flax strands. When woven together (raranga), the strands come together to produce a strong mat (kete). Wellbeing is best achieved, metaphorically, when the four capitals are all strong and supporting each other.

- The Four Capitals

Source: The Treasury

Source: The Treasury

Source: The Treasury

Businesses, households, and the government combine the four capital stocks in various ways to generate flows of tangible and intangible goods and services that enhance wellbeing now and in the future. Intergenerational wellbeing depends on the sustainable growth and distribution of the four capitals, which together represent the comprehensive wealth of New Zealand.

The Living Standards Framework is evolving, and the Treasury will be doing further work to ensure it is in synergy with te ao Māori. While many concepts already reflect a Māori worldview of te pae tawhiti (a long-term, intergenerational view), whanaungatanga (connectedness) and kaitiakitanga (guardianship), work continues to further refine and test this framework.

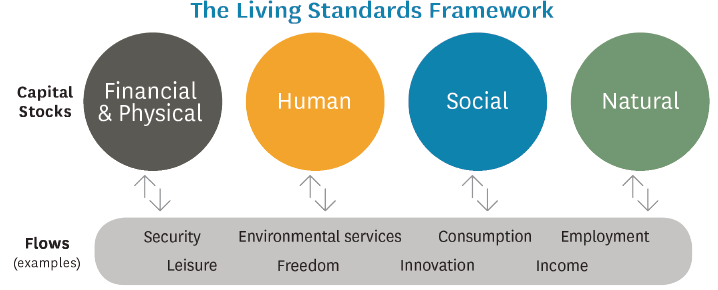

- The Living Standards Framework

Source: The Treasury

Source: The Treasury

Source: The Treasury

The Framework is intended to be a flexible tool that can help identify dynamics and trade-offs across social, economic, and natural domains.

These dynamics are complex, and our knowledge about them is incomplete. The Framework is intended to encourage analysis that pushes beyond the more easily measured (but narrow) financial dimensions, and to identify complementarity, substitutability, interactions and trade-offs between the different capital stocks.

The Living Standards Framework has aspects in common with other, international frameworks developed overseas. New Zealand is a signatory to the Sustainable Development Goals - a collection of 17 global goals set by the United Nations. The goals are more outcome-specific than the four capitals, but capture many of the same ideas.

The key benefit of applying the Living Standards Framework to policy analysis is therefore that it encourages a broad consideration of the wellbeing impacts of policy change. In this spirit, the Group encourages people reading and responding to this paper to explore and share their own views about how the design of the tax system affects the wellbeing of New Zealanders.

The established criteria that have been used in past tax reviews (both domestically and overseas) are also useful when considering the costs and benefits of various reforms. These criteria include:

- Efficiency: Taxes should be efficient and impose as little cost on society as possible. By this it is meant that taxes should be imposed in a way to maximise national welfare, by not creating biases between different investments or activities, unless there are sound reasons to believe that there are wider social costs that these taxes are addressing.

- Equity and fairness: The tax system should be fair. This involves both horizontal equity (fair treatment of those in similar circumstances) and vertical equity (fair treatment of those with differing abilities to pay tax).

- Revenue integrity: The tax system should minimise opportunities for tax avoidance and arbitrage and provide a sustainable revenue base for the government.

- Fiscal adequacy: The government should raise sufficient revenue to meet its requirements.

- Compliance and administration costs: Taxpayers' costs of complying with the tax system and the government's costs of administering the tax system should be kept to a minimum. One important aspect of this is to provide as much certainty to taxpayers as possible as to what tax is due.

- Coherence: Individual reform options should make sense in the context of the entire tax system. While a particular measure may seem sensible when viewed in isolation, implementing the proposal may not be desirable given the tax system as a whole.

Coherence is really a means of satisfying the other objectives outlined above rather than being an end in itself. A coherent tax system is one that fits together. For example, it is common internationally for governments to decide that personal income should be taxed at a set of increasing marginal tax rates. For such a system to be coherent it is vital that the statutory tax rates on personal income “stick”. The tax system loses coherence if this progressive tax system can be circumvented by, for example, individuals sheltering income in trusts or companies. Similarly, the tax system loses coherence if there are arbitrary differences in the ways that different forms of savings or investment are taxed.

Distribution and equity

Taxation has a number of fairness implications. The taxes imposed on each person must be seen to be fair in light of the person's income, consumption, wealth, or other measure in relation to other people subject to the tax. Fairness implications are usually referred to as ‘equity' considerations in tax policy.

What is fair to one person might not seem fair to another. To help frame this difficult discussion, tax policy has traditionally relied on the concepts of horizontal and vertical equity to guide reform.

Horizontal equity is a principle whereby those in the same circumstances should pay the same amount in taxes. Vertical equity is a principle whereby those in better circumstances should pay higher amounts (and often higher proportions of income and/or assets) in line with their greater economic capacity to pay. As expressed through the political system, it is clear that New Zealand as a society accepts that a progressive tax system (where those on higher incomes pay higher proportions of tax) is a fair system.

The Group also understands that a key part of horizontal equity relates to the rules that apply to different structures. Some people have more than one option for structuring their business affairs, whereas others do not. For example, an employee will always have tax deducted at source by their employer through the PAYE system. A contractor doing broadly equivalent work may be able to conduct their business as either a sole-trader, a partner in partnership, through a company or through a trust. Such decisions can allow tax rate benefits as well as the ability to access work-related deductions. This has implications for horizontal equity.

It is also important to recognise that sometimes the principles of horizontal and vertical equity are, for various reasons, not adhered to. Inconsistencies in the system are referred to in Chapter 5.

Another important aspect of fairness is procedural fairness. Taxpayers should have as much certainty of their tax situation as possible, and should be treated fairly by the tax department.

The adequacy of the personal tax system and its interaction with the transfer system is outside the scope of the Group's review (the Terms of Reference note that this will be considered as part of a separate review of the welfare system). However, when looking at fairness as a concept, the Group considers that the amount of tax paid per person or group is only one side of the consideration. Because tax revenue is used to fund government services, looking at how the tax revenue is spent and on whom it is spent are also an important part of the fairness question.

Therefore, when thinking about the distribution of taxes, equity and fairness, it is best to think of the tax and transfer system overall, rather than individual taxes in isolation.

Efficiency and other impacts of tax

Tax funds expenditure that raises the living standards of New Zealanders, both collectively and individually. Without the revenue to fund that expenditure, the public goods that households and businesses enjoy would be absent.

Tax policy generally focuses on how to raise that revenue in the fairest and most efficient way possible. Putting aside the ‘use' of the revenue, transferring the equivalent of a third of GDP from individuals and entities in the economy to government may have (usually unwanted) other impacts. Tax policy concentrates on how to raise the revenue at the least cost to society.

The unwanted impacts are sometimes called the deadweight costs of taxation. These are costs imposed on society by people changing their behaviour in response to the tax. For example, if two different investments were taxed at different rates, the tax system would be inducing people to invest in the more lightly-taxed investment. This will mean that even when a lightly-taxed investment is making lower returns before tax, investors may still invest in it because its after-tax returns are higher. This is a cost because society will end up poorer as investment is directed toward investments with lower pre-tax returns, solely for tax reasons, rather than the most efficient investments.

Another example is tax on income from labour. In the absence of taxation, the private returns from working would be higher. In such a situation, people might make different choices about how often they work and for how long, and at what sort of job. In short, labour taxation changes the relative reward to work and this can cause people to change their behaviour.

In the business context, a tax system will be least distortionary if it taxes economic income and provides deductions for the true cost of inputs in creating that income. This is because a tax on profits (i.e. after allowing deductions for costs) will generally lead to firms continuing to make similar businesses decisions with a tax that they would without the tax.

As an example, consider a firm that can spend $9 to make $10 in revenue. If there is a 20% tax on profit then the firm will still have the incentive to make the investment as they will make a post-tax return of $0.80 (that is, 80% of the $1 profit). However, if instead the firm was not allowed to take deductions and there was a 20% tax on revenue, the firm will not make the investment because after tax they will make a $1 loss (they would be taxed $2 on the $10 revenue).

Other taxes that promote efficiency seek to ensure that consumers and producers face the social costs of their activities. These taxes try to approximate the social costs of an activity. A tax or price on traffic congestion is one example of this.

Tax incidence

One other important principle is that of tax incidence. This principle intersects both fairness and efficiency considerations. Tax incidence is about who ultimately bears the costs of a tax. A good example is excise tax. While firms that produce alcohol and tobacco are statutorily and administratively liable for excise tax, it is normally assumed that the incidence (that is, who actually bears the cost of the tax) is felt by consumers of these products.

Another example is a payroll tax. A payroll tax is paid by an employer, generally as a percentage of an employee's wages. While the employer administratively pays the tax to the tax department, employees' wages may be reduced by some or all of the tax. The result is that the employee pays the tax to the extent his or her wages are reduced. The incidence point is an important point because if we confuse statutory incidence with who really bears the cost of the tax, our intuitions may lead to erroneous conclusions on fairness. While it is hard to estimate actual incidence with precision, it is vital to keep in mind when thinking about tax changes.

4 The current New Zealand tax system

- New Zealand's ‘broad-based, low-rate' system, with few exemptions for GST and income tax, has been in place for over thirty years. Looking to the future, is it still the best approach for New Zealand? If not, what approach should replace it?

- Should there be a greater role in the tax system for taxes that intentionally modify behaviour? If so, which behaviours and/or what type of taxes?

- Should the tax system encourage saving for retirement as a goal in its own right? If so, what changes would you suggest to achieve this goal?

This chapter compares New Zealand's tax system to others in the OECD to provide an international perspective. International comparisons are always difficult because inevitably there are nuances that make like-with-like comparisons difficult. Nevertheless, comparisons can be useful to provide context for New Zealand. Other countries can and do have tax systems that vary materially from New Zealand's own.

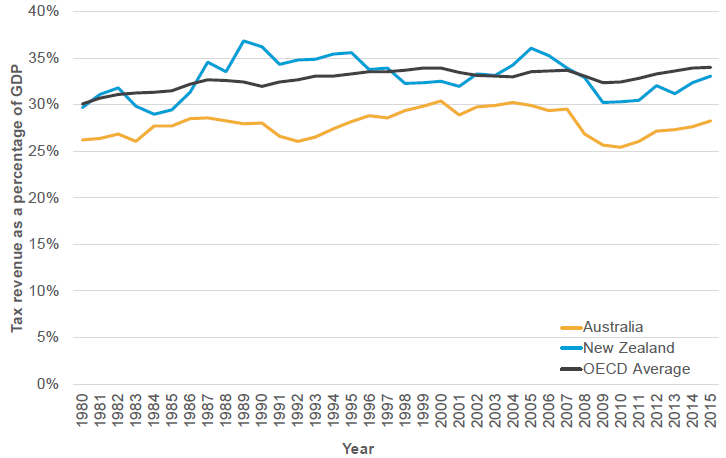

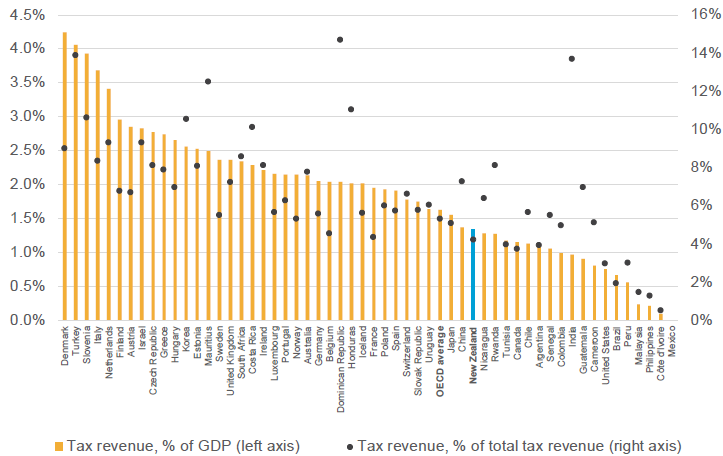

How much does New Zealand tax?

In New Zealand, the central government spends an amount equivalent to about 30% of GDP on services and transfers, so it needs to raise about the same amount of revenue each year in order to maintain spending without increasing debt. Over time there has been some fluctuation in government revenue, with the current level slightly below the OECD average of tax revenue equivalent to 34% GDP, as illustrated in Figure 3. Note that these OECD figures include local government taxes (such as rates) for ease of comparison, but the Group is not considering any changes to local government taxation in New Zealand.[18],[19]

- Figure 3: Tax revenue as a percentage of GDP

Source: OECD

Source: OECD

What does New Zealand tax?

In general terms, a tax base refers to the application of tax to a revenue stream or activity. The largest tax bases for central government in New Zealand are:

- Individual income (individual income tax)

- Company income (company income tax)

- General consumption (goods and services tax)

- Consumption of specific goods and services (excise taxes imposed on sales of tobacco products, alcoholic drinks, and motor fuels)

Broad base, low rate

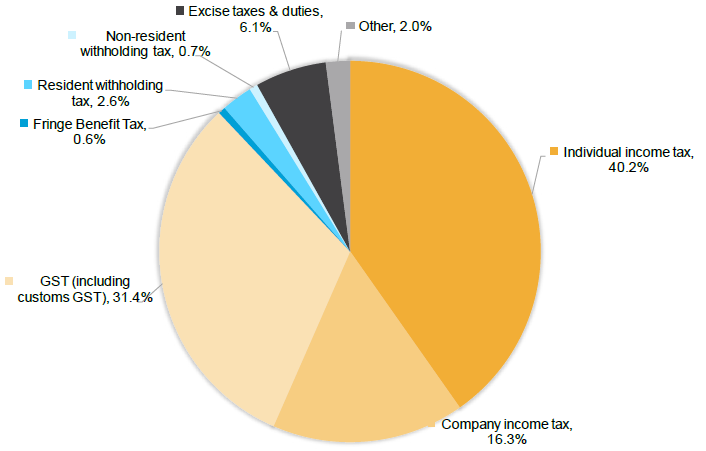

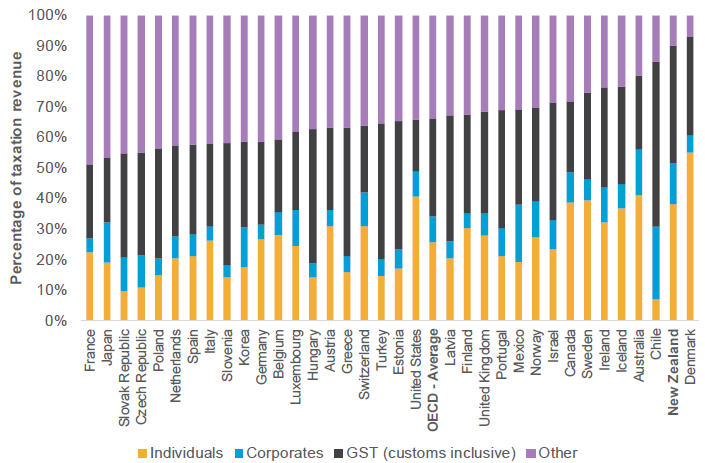

New Zealand is generally described as having a “broad-based, low-rate” tax system. This refers to the tax base, and tax rate. A broad base means that few things are exempt from a particular tax. As shown in Figure 4, New Zealand gets approximately 90% of its tax revenue from three tax bases (excluding local government taxes) - individual income, company income, and general consumption. This is a more concentrated source of revenue than most OECD countries, which raise significant proportions of revenue from social security contributions and payroll taxes, as shown in Figure 5.[20]

- Figure 4: New Zealand source of taxation revenue (2017)

Source: The Treasury

Source: The Treasury

- Figure 5: Source of taxation revenue 2015 - OECD countries

Source: OECD

Source: OECD

One example of a broad-based tax in New Zealand is our GST, which has almost no exemptions. Similarly, our income tax has few exemptions (one notable gap is particular capital gains). In contrast, other countries' tax systems often allow deductions for things like superannuation contributions, health care expenses, and mortgage interest on owner-occupied dwellings.

Having a broad tax base allows New Zealand to raise substantial tax revenue with relatively low tax rates. Fewer exemptions also means a simpler tax system and less opportunity for tax avoidance. The top income tax rate in New Zealand is currently 33%, which is low for developed countries. Our GST rate of 15% is also low internationally.

Unlike many other countries, New Zealand does not have a tax-free threshold on income earned by individuals, companies or trusts. Consequently, our income tax applies broadly - from the very first dollar of income. Although they often have a tax-free threshold, most other OECD countries have a payroll tax or social security tax that applies to the first dollar of wage income. When these are included, for 2016 New Zealand has the lowest average effective tax rate in the OECD for families with children.[21]

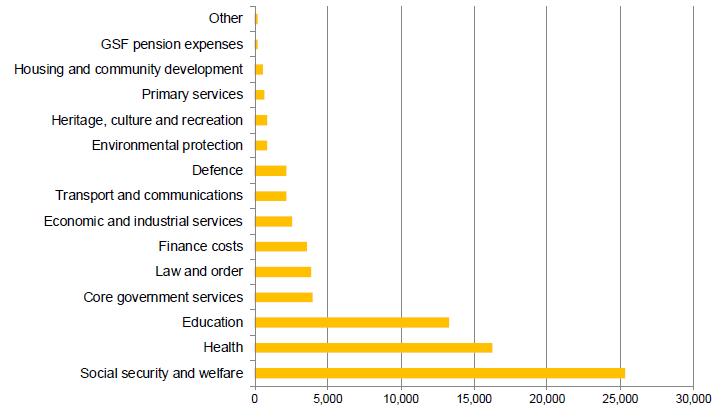

The Government spends in a variety of areas, as shown in Figure 6, but the three primary areas are social security and welfare (which includes NZ Superannuation), health, and education.[22]

- Figure 6: Core Government Expenses (Year ending 30 June 2017)

Source: The Treasury

Source: The Treasury

Taxes and behaviour

Some tax systems aim to incentivise certain types of behaviour. There are two main justifications for using tax to modify behaviour.

The first justification is that an activity has social costs (and so is taxed at a higher rate), or has social benefits (and so is taxed at a lower rate or subsidised). These are taxes based on externalities and are sometimes called Pigouvian taxes. Environmental taxes often have these goals. Pigouvian taxes are consistent with a broad-based low-rate system.

The second justification is that an activity may be harmful or beneficial to an individual, and for some reason the individual may not be able or willing to act in their best interest. The tax therefore seeks to discourage the individual from partaking in the harmful behaviour.

New Zealand does, in a few selected cases, deliberately incentivise or discourage particular behaviour (for example, tobacco and alcohol excise tax). Recently there have been calls for further exceptions - in particular for sugary drinks.

Tax and retirement savings

In New Zealand, personal income from capital (other than some non-taxed capital gains) is taxed at the same rate as income from labour under our income tax. Some commentators think that New Zealand should tax income from capital at a lower rate to encourage more saving, particularly for retirement. New Zealand's lack of concessions for retirement savings is rare among OECD countries. However, the Government does provide material support to those in retirement through universal superannuation - expenditure on payments of New Zealand Superannuation is expected to be $13.7 billion in the 2017/18 financial year - more than all other benefit payments combined.

When thinking about retirement savings, there are three possible taxation points. These are: at the stage of contribution, when the contribution itself earns income, and when all savings (the contribution and the income earned on the contribution) are withdrawn. In most OECD countries, contributions to retirement savings are made out of income that is not taxed. Investment earnings on retirement savings are also exempt, and it is not until the drawdown phase where withdrawals of capital and accumulated earnings are taxed. This approach is often described as EET - Exempt-Exempt-Taxed. At the same time, social security pensions are means-tested in many countries. This means that additional retirement savings directly reduce the cost of social security pensions to the government (because wealthy individuals do not qualify for a means-tested pension), which may partially explain why these countries provide tax concessions for retirement savings.

New Zealand takes a different approach to most other countries. Our comprehensive income tax is often described as TTE - Taxed-Taxed-Exempt. This means that contributions are made out of income that is taxed (usually an individual's labour income), the income earned from the investment is taxed (regardless of whether it is earned before or during retirement), but amounts “withdrawn” from the investment are not taxed. This approach ensures that economic distortions to save in a retirement account instead of through other savings are minimised.[23] New Zealand is also unusual compared to other OECD countries in that New Zealand Superannuation is universal, so additional retirement savings do not reduce the amount of New Zealand Superannuation paid out. If New Zealand were to switch to a system where income earned on the investment was not taxed, the fiscal cost would be significant.

Along with the non-taxation of particular capital gains, there are other exceptions to New Zealand's general tax neutrality across different types of savings - some small concessions for retirement savings have been introduced in recent years with the establishment of Portfolio Investment Entities (PIEs) and KiwiSaver, both in 2007.

KiwiSaver provides modest incentives to save for retirement, and the automatic enrolment of employees when they take up new jobs means that many people are ‘nudged' into saving.

5 The results of the current tax system

- Does the tax system strike the right balance between supporting the productive economy and the speculative economy? If it does not, what would need to change to achieve a better balance?

- Does the tax system do enough to minimise costs on business?

- Does the tax system do enough to maintain natural capital?

- Are there types of businesses benefiting from low effective tax rates because of excessive deductions, timing of deductions or non-taxation of certain types of income?

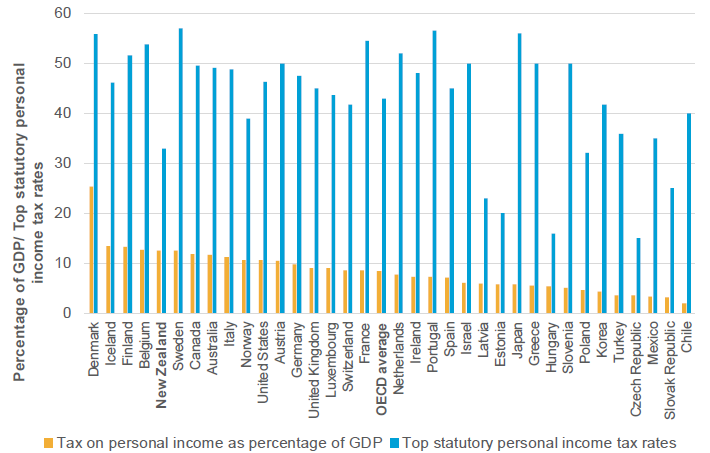

Individual income tax

The New Zealand tax system raises relatively high amounts of revenue considering its relatively low rates. The comparison of OECD countries in Figure 7 shows New Zealand collects the fifth highest proportion of taxes on personal income as measured against GDP, despite having the sixth lowest top statutory personal rate. This can be explained by New Zealand's relatively low threshold for the top marginal personal tax rate ($70,000) compared to our average wage. This suggests that New Zealand's broad-base low-rate system lives up to its name in collecting large amounts of revenue by taxing income earned by individuals broadly, but at relatively low rates.

It is important to note that the personal income taxes in the above chart do not include social security contributions or payroll taxes. While New Zealand does not have any of these, other OECD countries do.

- Figure 7: Taxes on personal income as percentage of GDP (2015)

Source: OECD

Source: OECD

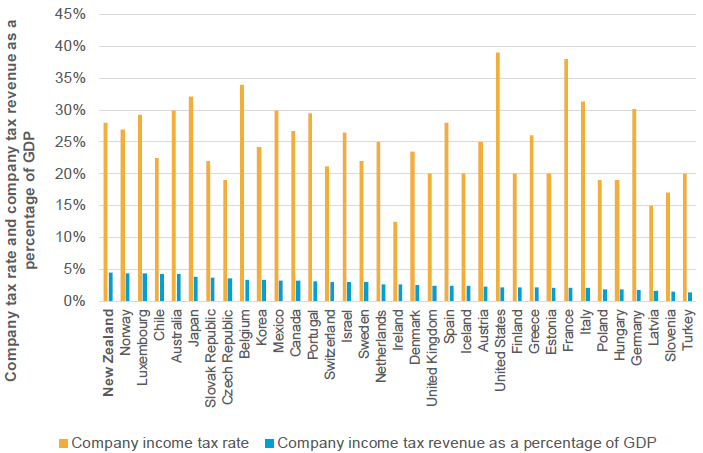

Company income tax

In the year ended 30 June 2017, the Government collected $12.6 billion in company tax.[24] This represents 4.6% of GDP in 2017.[25] In 2015, New Zealand's collection of company tax was the highest in the OECD as measured as a proportion of GDP (as shown in Figure 8), but when New Zealand data is reported on a consolidated[26] basis it is the fifth highest in the OECD.[27] Once more this suggests a broad and robust tax base. It should be noted, however, that New Zealand's company tax rate is higher than average. As at 2017 New Zealand has the tenth highest company rate of the 35 OECD countries.[28]

Because of New Zealand's imputation system, there is only limited additional tax at the shareholder-level when dividends are paid out of income that has been taxed at the company level. This additional tax applies for taxpayers on the top marginal rate, and is the difference between the corporate rate and the taxpayer's marginal tax rate. Many other countries have an additional layer of tax at the shareholder level for domestic shareholders with no credit for tax at the company level. Those additional shareholder-level taxes are not taken into account in Figure 8 but are taken into account in the taxes on personal income in Figure 7. When factoring in imputation, New Zealand's tax rate on domestic shareholders is the sixth lowest in the OECD.

- Figure 8: Company income tax rates and revenues (2015)

Source: OECD

Source: OECD

The company tax rates in Figure 8 are statutory rates. If some sectors of the economy habitually pay lower effective rates, perhaps because they can apply excessive deductions, or benefit from timing regimes or some of their income is not taxed, it may be appropriate to consider whether those tax concessions are still relevant and fair. Conversely, some business expenses may not be deductible under existing rules and consideration should be given to whether this is appropriate.

Goods and services tax

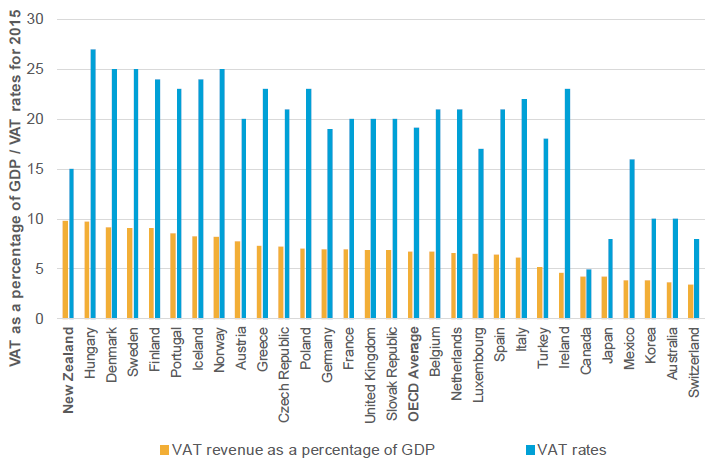

GST is a broad-based value-added tax on general consumption in New Zealand imposed at a single rate of 15 percent with very few exemptions. Having few exemptions and a single rate creates a relatively simple system. However, there are concerns that New Zealand's GST is regressive in that lower-income households tend to pay a larger proportion of their income in GST.

New Zealand's GST is among the most comprehensive in the world. To the extent there are exemptions, they pale in comparison to the multitude of exemptions and differential rates across the rest of the world. As shown in Figure 9, New Zealand collects the highest equivalent percentage of GDP through its GST in the OECD (based on 2015 data), despite having one of the lower value-added tax rates across the OECD. This reflects a very broad GST base, but also a different treatment of government spending compared to other countries. If we were to calculate GST on government spending on the same basis as other countries, we would have the eleventh highest level of GST as measured against GDP.

Goods and services excluded from GST include financial services, and low-value imported goods.[29]

- Figure 9: Value-added taxes as a percentage of GDP (2015)

Source: OECD

Source: OECD

Financial services are difficult to apply GST to because it is difficult to isolate and separate out the service provided by financial institutions from the savings component of a loan. Banks and financial institutions generally charge for the service they provide through a margin between the interest rate that they charge and the interest rate that they pay. In principle this charge for the service should be subject to GST, but it is difficult to accurately identify the amount of this margin on a transaction by transaction basis and therefore difficult to apply GST to it.

Due to the growth of online shopping there is an increasing volume of imported goods on which GST is not collected. This is because the GST (and other duties) owing on these goods is below an administrative de minimis. The rationale for the de minimis is to achieve a balance between the administrative costs of collecting the GST at the border and the revenue collected, as well as to facilitate the clearance of goods at the border. The Group has been asked for advice on this by the Minister of Finance and has already provided that separately.

Recent developments suggest there may be cost-effective options for collecting GST on low value imported goods. In particular, from 1 July 2018 Australia will become the first country to require offshore suppliers that sell more than AU$75,000 per year of goods valued below AU$1000 to Australian consumers to register for and charge GST on these sales. This follows on from the fact that many countries, including New Zealand, have required offshore suppliers of digital services to domestic residents to register for and collect GST.

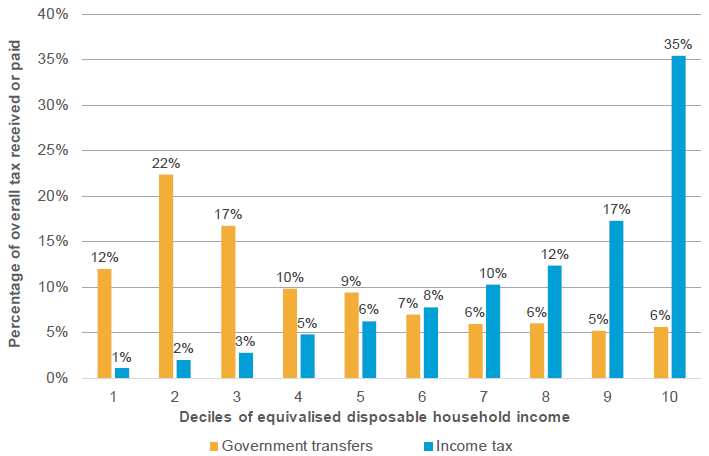

Cash transfers and income tax paid

The following charts give indications of the level of redistribution given by New Zealand's tax and transfer system. It is important to note that the income measure used for these charts does not include untaxed capital gains and some other important benefits associated with owner-occupied housing. As a result, it will understate the income of some households, in particular some higher income households. A related issue is that this is based on survey data, and surveys exclude extreme outliers, particularly those who have extremely high incomes or wealth. It should also be noted that the transfer measures used only include cash transfers and not other government spending that can reduce inequality such as education or health spending.

- Figure 10: Percentage of income tax and transfers across deciles

Bryan Perry, Ministry of Social Development, 2017. Data based on Household Economic Survey 2015

Bryan Perry, Ministry of Social Development, 2017. Data based on Household Economic Survey 2015

Higher-income households play an important role in funding the government. Figure 10 illustrates how the share of all income tax paid increases as household income increases over the deciles - with decile 1 being the 10% of households with the lowest incomes and decile 10 being the 10% with the highest household incomes.[30] Households in the top income decile pay one third (35%) of all income tax collected while receiving 6% of all transfers (almost entirely from New Zealand Superannuation).[31] Those in the bottom five income deciles collectively pay less than 20% of all income tax.

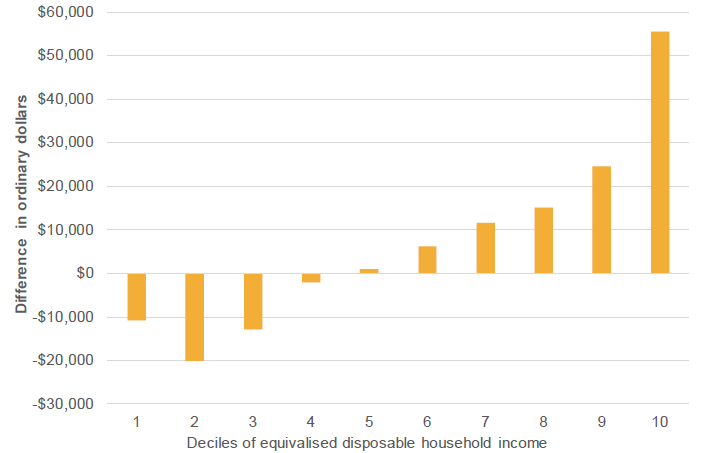

Figure 11 shows the difference between income tax paid and government transfers for each household income decile. For the bottom four income deciles the amount households receive in transfers is greater than what they pay in income tax. The difference is greatest for decile 2 households, which is due to the high number of New Zealand Superannuation recipients in this group.

- Figure 11: Income tax less government cash transfers

Bryan Perry, Ministry of Social Development, 2017. Data based on Household Economic Survey 2015

Bryan Perry, Ministry of Social Development, 2017. Data based on Household Economic Survey 2015

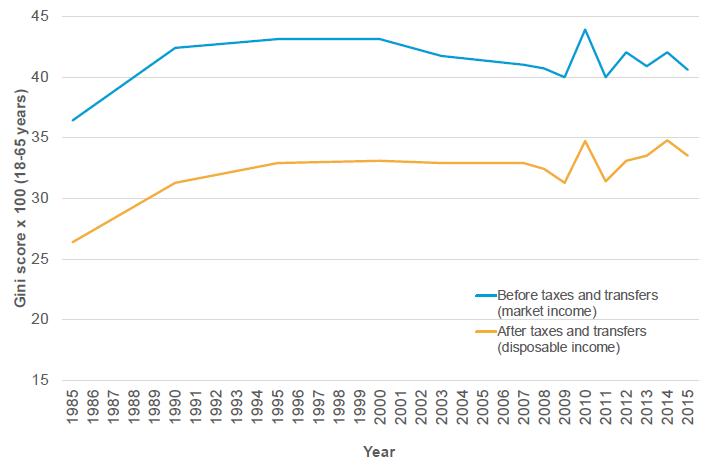

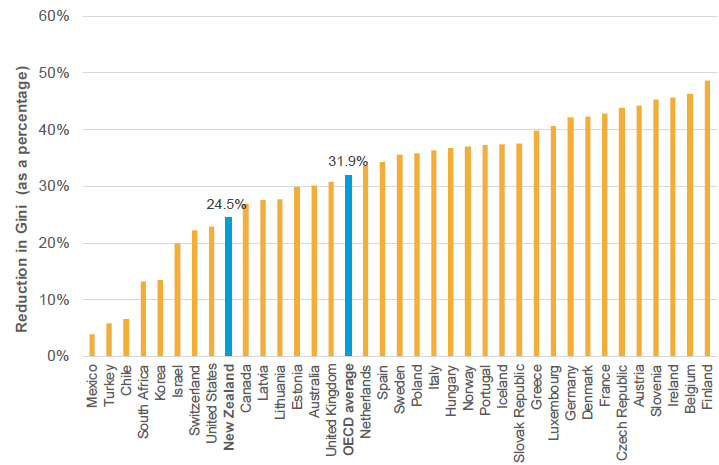

Income inequality refers to the uneven distribution of income among households. Income inequality is often used as a measure of fairness across society. Figure 12 shows the inequality-reducing impact of taxes and transfers by comparing the ‘Gini' scores for households before and after taxes and transfers.[32]

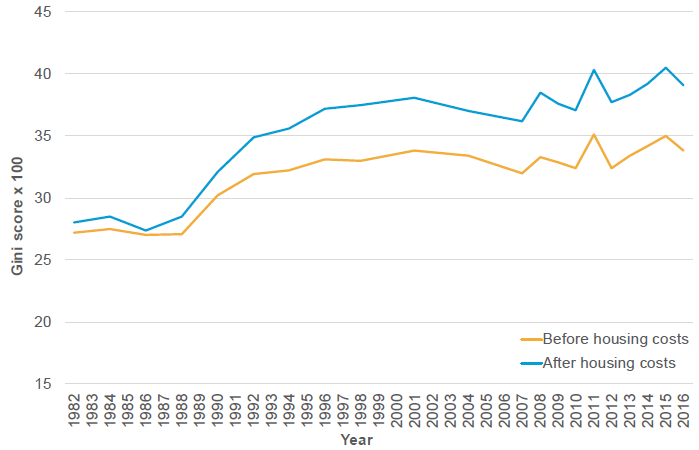

Inequality is greater when considering household income after housing costs. Figure 13 shows that inequality after housing costs has been increasing over time. This reflects both that housing costs generally make up a greater proportion of household income for lower income households than for higher-income households, and that housing costs have been growing faster than incomes.[33]

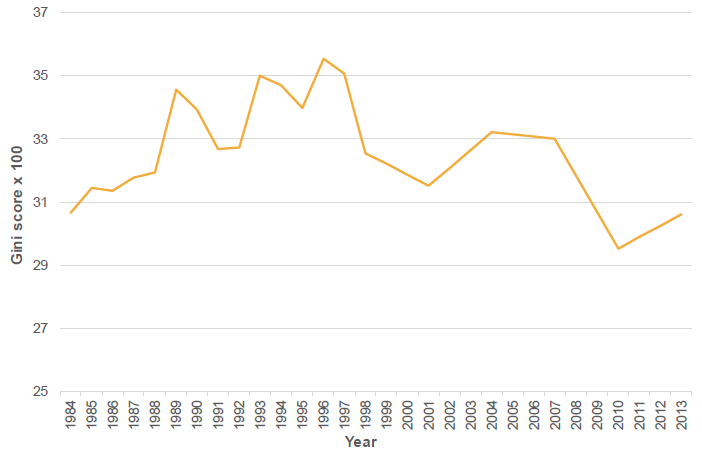

Looking at expenditure inequality is also a useful indicator. Income inequality is partly attributable to households having different incomes over their lifetime (generally relatively low when young, high when middle aged, and low when retired). The other limitations of income data are that it excludes capital gains and imputed rents, and will not account for income earned in entities owned by the household or individual (e.g. trusts, companies). Looking at expenditure inequality mitigates these problems. Expenditure data has less of a lifetime income problem as households will generally “smooth” their consumption to some extent and try to consume based on their expected lifetime income. If households or individuals have received substantial capital gains, or have income in entities, this will influence their expenditure, which will tend to increase with their greater income or wealth.

- Figure 12: Income inequality before and after taxes and transfers

Source: Bryan Perry, Ministry of Social Development, 2017

Source: Bryan Perry, Ministry of Social Development, 2017

- Figure 13: Income inequality before and after housing costs

Source: Bryan Perry, Ministry of Social Development, 2017

Source: Bryan Perry, Ministry of Social Development, 2017

- Figure 14: Inequality of household spending 1984 to 2013: Expenditure

Source: Treasury WP 15/06: Inequality in New Zealand 1983/84 to 2013/14

Source: Treasury WP 15/06: Inequality in New Zealand 1983/84 to 2013/14

At the same time, expenditure data has its own limitations. Survey data on expenditure systematically fails to match national aggregate data. The survey data tends to underestimate consumption, suggesting some under-reporting of expenditure by survey recipients.

Similar to income inequality, the expenditure inequality measure in Figure 14 shows increasing inequality from 1984 until the mid-1990s. However, unlike income inequality, expenditure inequality has decreased since the mid-1990s. Expenditure inequality is an aggregate concept and there can be important nuances that are not picked up in aggregate measures if the price of particular goods and services has changed over time.

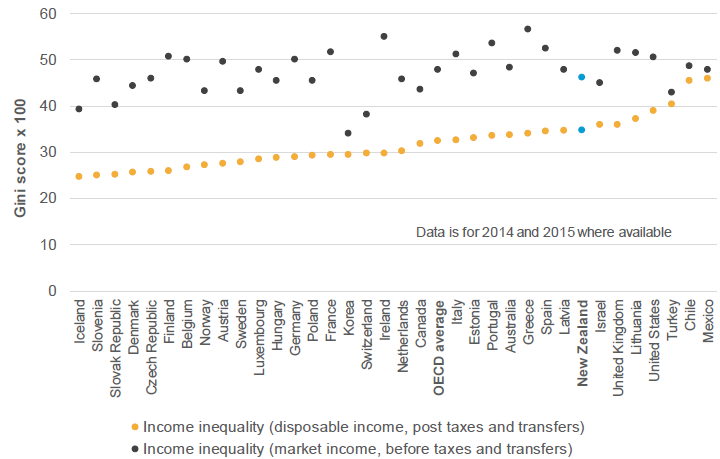

Figure 15 shows that, compared with other OECD countries, New Zealand's level of income inequality is above average and higher than Australia, although lower than the United Kingdom and United States.

New Zealand's tax and transfer system provides a similar reduction in measured income inequality to Canada, but a smaller reduction than Australia or the OECD average, as shown in Figure 16.

Other countries have chosen to have high tax and high transfer systems. The Scandinavian countries are good examples of these systems. Transfers tend not to be targeted, with the result that the fiscal cost requires substantial taxation. To date, New Zealand has used a more targeted approach. This reduces the fiscal cost of transfers, which allows lower taxes. This more targeted approach does result in high effective marginal tax rates on lower income-households as benefits are withdrawn as earnings increase, and it limits the redistributive power of the system as a whole.

- Figure 15: Income inequality in OECD countries (2014/15)

Source: OECD

Source: OECD

- Figure 16: Reduction in the Gini coefficient on account of the tax and transfer system

Source: OECD

Source: OECD

The Ministry of Social Development's Household Incomes in New Zealand report summaries the inequality-reducing power of New Zealand's tax and transfer system in the following way:[34]

- The inequality-reducing power of the tax and transfer system on market income inequality has steadily declined for New Zealand from 27% to 17% over the last three decades (using the Gini).[35]

- The size of the impact reflects not only the original level of household market income inequality but also changes in policy settings and in the number of people receiving a main working-age benefit (the latter has declined since the mid-1990s except for a brief rise following the Global Financial Crisis).

- The inequality-reducing power of New Zealand's tax-benefit system is currently relatively low compared with that for other OECD countries, including those who (like New Zealand) have lower unemployment rates (for example, Germany, Norway, the UK and Australia). It is below the OECD average.

This Group's Terms of Reference exclude consideration of “the adequacy of the personal tax system and its interaction with the transfer system” and instead, the Government has indicated its intention to review the welfare system. The Tax Working Group will, however, be looking at the fairness of the tax system; an important part of the tax and transfer system.

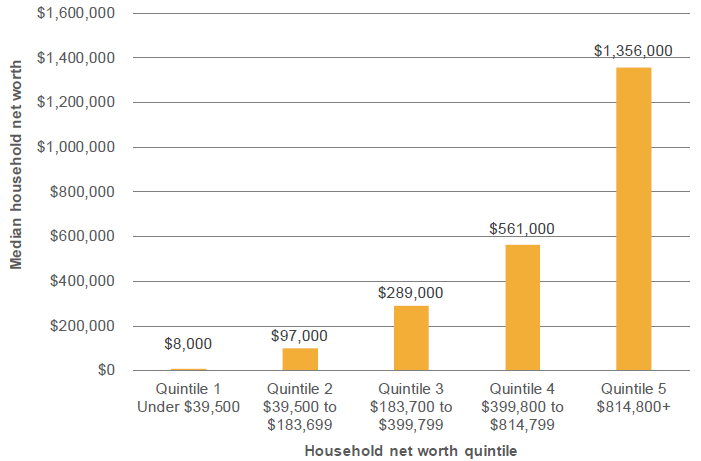

Wealth inequality

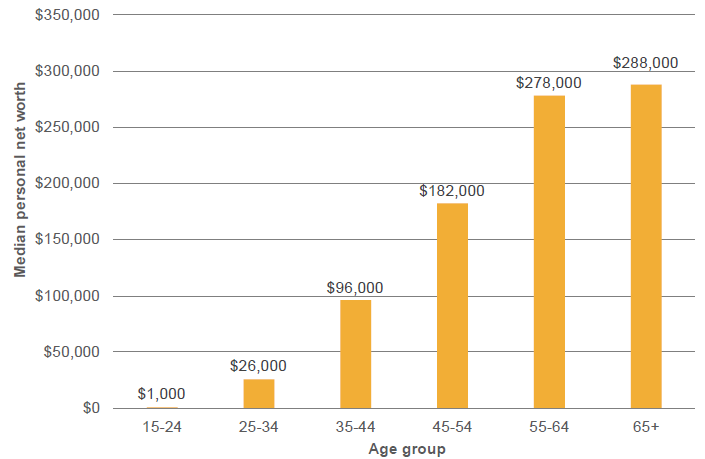

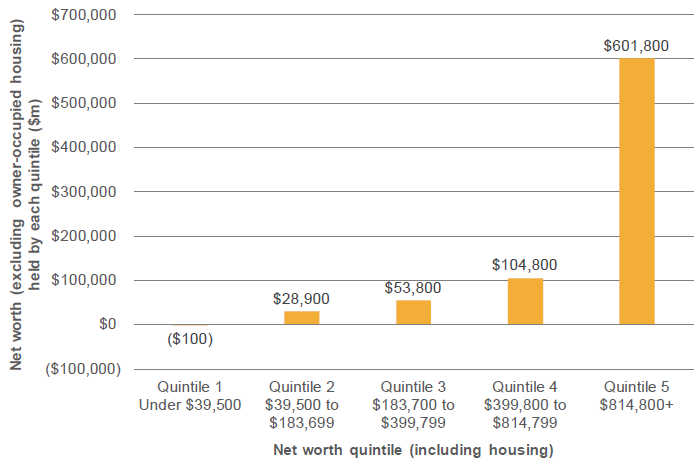

The central government taxes income and consumption, but not wealth. Wealth is distributed much less equally than income. Figure 17 illustrates the level of wealth inequality among households.

Part of the reason is that wealth tends to depend on age as people accumulate assets through their working lives. On average older people are wealthier than younger people, as shown by Figure 18. There is also likely to be substantial wealth inequality within each age group. Owner-occupied housing is also strongly associated with higher-wealth quintiles: 40% of owner-occupied housing (by value) is held by the 20% of households with the highest net worth, while 1% is held by the 20% of households with the lowest net worth.[36]

Excluding owner-occupied housing from the wealth statistics, illustrated in Figure 19, also shows that the vast majority of non owner-occupied housing wealth is held by the wealthiest quintile.

- Figure 17: Median household net worth by quintile (2015)

Source: Household net wealth statistics, Statistics New Zealand

Source: Household net wealth statistics, Statistics New Zealand

- Figure 18: Median personal net worth by age group (2015)

Source: Household net wealth statistics, Statistics New Zealand

Source: Household net wealth statistics, Statistics New Zealand

- Figure 19: Net worth (excluding owner-occupied housing) held by each net worth quintile ($m)

Source: Household net worth statistics, Statistics New Zealand

Source: Household net worth statistics, Statistics New Zealand

- Figure 20: Average tax wedge faced in OECD countries (2016)

Source: OECD

Source: OECD

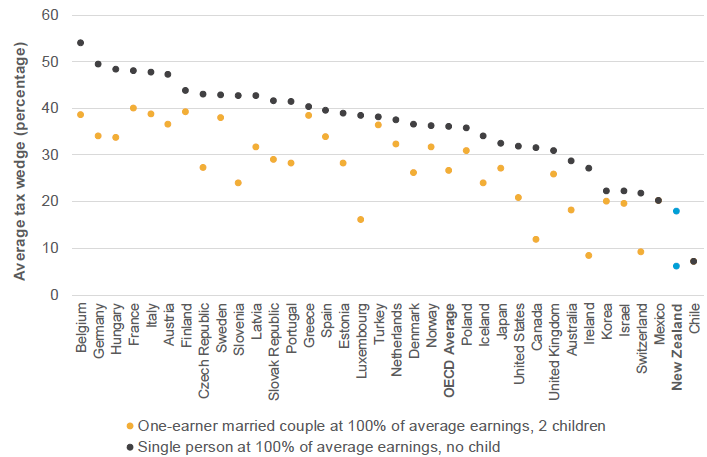

Average tax wedge