1 Introduction

1. The Government established the Tax Working Group to examine further improvements in the structure, fairness and balance of the tax system. The Terms of Reference asked the Group to consider whether a system of taxing capital gains (not applying to the family, or main, home or the land under it - referred to in this report as the ‘excluded home'), would improve the tax system.

2. The Government's objective, as stated in the Terms of Reference, is to have a tax system that:

- is efficient, fair, simple and collected

- promotes the long-term sustainability and productivity of the economy

- supports a sustainable revenue base to fund government operating expenditure around its historical level of 30% of GDP

- treats all income and assets in a fair, balanced and efficient manner, having special regard to housing affordability

- is progressive, and

- operates in a simple and coherent manner.

3. Whether a system of taxing capital gains can meet these objectives is dependent on the design features. This Volume outlines the detailed design decisions made by the Group for taxing capital gains. The Group's views as to whether a system of taxing capital gains based on these features would meet the above objectives are stated in Chapter 5 of Volume I.

4. This Volume builds on the decisions outlined in Appendix B of the Group's Interim Report and takes into account the Group's further thinking on the issues and feedback received from consultation on the Interim Report.

2 What should be taxed?

Included assets

1. The taxation of capital gains should be extended to a list of ‘included assets', being:

- land, including improvements to land (other than the excluded home)

- shares

- intangible property, and

- business assets.

2. Those assets, as well as the assets that should be excluded from an extension of the taxation of capital gains, are discussed in this chapter.

Land

3. In some circumstances capital gains from the sale of land are already subject to tax. Capital gains from the sale of all land, including improvements to land, and leasehold interests should be subject to tax. This includes residential property, such as rental properties, and second homes, including holiday homes, baches and cribs. This also includes all commercial, agricultural and industrial land.

4. However, gains from the sale of a person's main home will not be taxed (see the following discussion from paragraph 15 on the excluded home). Māori Freehold Land under Te Turi Whenua Māori Act 1993 could also be excluded from an extension of the taxation of capital gains (see following from paragraph 42).

Example 1: Rental property

Aroha owns a rental property. Any capital gains arising from the sale of the rental property (i.e. sale proceeds less allowable deductions for costs of acquisition and improvements (discussed in Chapter 4)) will be taxable income for Aroha.

Example 2: Holiday home

In addition to his main home, Jordan owns a holiday home in the Coromandel Peninsula. Any capital gain arising from the sale of the holiday home will be taxable income for Jordan.

5. Gains from the sale of land owned by a New Zealand resident, where that land is located in another country, will also be subject to tax. If a gain on land is taxed in the country in which it is located, New Zealand would allow a foreign tax credit to the extent of any double taxation.

Example 3: Foreign land

Manu owns a holiday home in Queensland, Australia. Any capital gains arising from the sale of the Queensland holiday home will be taxable income for Manu. To the extent that Manu is also taxed on his capital gain in Australia, he would receive a foreign tax credit that can be credited towards his New Zealand income tax liability.

Shares

6. All capital gains from the sale of shares in New Zealand and foreign companies[1] should be taxed. More detail on how shares should be taxed is discussed below in Chapter 7 Taxation of New Zealand shares and Chapter 8 Taxation of foreign shares.

Example 4: Share portfolio

James has a portfolio of shares in various New Zealand and Australian listed companies that he holds as a long-term investment. Any capital gains arising from the sale of the shares will be taxable income for James.

Example 5: Shares in a small business

Tama owns 100% of the shares in his small consulting company, Consult Me Limited. Any capital gains arising from the sale of the shares in Consult Me Limited will be taxable income for Tama.

7. However, most sales or redemptions of interests in portfolio investment entities (PIEs) including KiwiSaver funds, should remain exempt from tax. Income earned by a KiwiSaver or other managed fund will continue to be taxed in the fund. See the discussion in Chapter 9 Taxation of KiwiSaver and other managed funds.

Example 6: KiwiSaver fund

Rebecca has funds invested in a KiwiSaver fund. Rebecca will not be taxed when she withdraws her funds from the KiwiSaver fund.

8. Where a person (including a trustee) owns a share in a flat-owning company[2] and the person occupies part of the property owned by the flat-owning company as their main home, any sale of that share will not be subject to tax (see the discussion below from paragraph 16 on the excluded home).

Intangible property

9. All capital gains from the sale of intangible property owned or created for business purposes should be subject to tax, with specific exclusions where necessary. Intangible property, otherwise known as a ‘chose in action', represents all personal rights of property that can only be claimed or enforced by legal action. Examples include goodwill, intellectual property such as patents, trademarks and copyrights, software, debt instruments, contractual rights and insurance policies.

Example 7: Intangible property

Café Limited runs a café. The café has developed goodwill through its operations. It also holds a registered trademark in respect of its logo.

If the business is sold, any capital gains arising from the sale of the goodwill and trademark will be taxable income for Café Limited.

10. Given the breadth of asset types that the term ‘intangible property' covers, it is impossible to provide a comprehensive list of particular types of intangible property. While a wider approach may initially create some additional uncertainty, in the longer term it should provide greater certainty, as it should mean fewer periodic updates. It will also likely lead to a relatively quicker discovery of any further areas that should be excluded.

11. The following items of intangible property should be expressly excluded from the scope of an extension of the taxation of capital gains:

- intangible property that is already subject to tax under the financial arrangement rules, (e.g. debt instruments and derivatives), and

- intangible property that is held for personal use (discussed further in paragraph 39).

12. As part of the Government's policy development and consultation process (generic tax policy process) further consideration should be given to other types of intangible property that should be specifically excluded from the extension of the taxation of capital gains. In particular, further consideration should be given to:

- traditional cultural assets, including Māori cultural assets[3]

- how an extension of the taxation of capital gains will interact with other intangible property that is already subject to specific rules that tax the increase in value of the asset, e.g. patent rights, emissions units under New Zealand's Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS), forest cutting rights and petroleum permits.

13. Consideration should also be given to whether any of those specific rules for intangible property can be rationalised in light of an extension of the taxation of capital gains.

Business assets

14. Capital gains from the sale of all other assets held by a business, or for income-producing purposes should be taxed. This would include depreciable assets, e.g. plant and equipment but would not include trading stock, i.e. stock that is held for the purpose of trading it as part of a business. Trading stock and revenue account property (discussed in paragraph 46) would continue to be taxed under the current rules.

Example 8: Mechanic business

Mechanic Limited runs a mechanic business. Mechanic Limited's assets consist of the land and buildings that it operates out of, various plant and equipment and the goodwill that it has generated over the time the business has been operating. It also has a stock of parts that it uses in the course of its business.

If the business is sold, any capital gains from the sale of the land and buildings, plant and equipment and goodwill, will be taxable income for Mechanic Limited.[4] However, sales of the parts in the course of carrying on Mechanic Limited's business will not be subject to the new tax. Instead, sales of the parts will be taxed under the current trading stock rules.

Excluded assets

15. While there is a list of included assets, rather than taxing all capital gains, there are some assets that should be explicitly excluded (some of which are discussed elsewhere). This section discusses:

- the excluded home, and

- personal-use assets.

The excluded home

16. The Terms of Reference require that the Group excludes the family, or main, home and the land under it from any extension of the taxation of capital gains. Therefore, there should be an exclusion for a person's family, or main, home (the excluded home).

17. The rest of this section explains the definition of an excluded home.

What is an excluded home?

18. An excluded home should be defined as the place that a person owns, where they choose to make their home by reason of family or personal relations or for other domestic or personal reasons. This test is based on the test used in s72(3) of Electoral Act 1993.

Example 9: Place that is a person's home

Piri owns a property in Wellington. He lives in the property and keeps all his possessions there.

The Wellington property will be Piri's excluded home. It is the place that he owns where he chooses to make his home.

19. Usually, a couple will only have one excluded home between them, because there will only be one place that they choose to make their home together. However, where a couple ends their relationship and subsequently live separately, they should each be allowed a separate excluded home. In rare situations, it may be possible for a couple to live separately and have separate excluded homes. However, this would only be allowed for a period of three years.

Example 10: Couple has separated

Natalie and Sarah have been married for 7 years. During that time they lived together in a home in Tauranga. Their relationship breaks down and they decide to end their relationship. Natalie remains in the Tauranga house and Sarah purchases a new home.

Prior to their separation, the Tauranga house was Natalie and Sarah's excluded home. However, after their separation, Natalie and Sarah have separate properties where they choose to make their homes. Therefore, from the time of their separation, they can each have a separate excluded home.

Example 11: Separate homes

John and Trudy are married. However, they each own separate homes they acquired before meeting each other. The homes are each separately (not jointly) owned by John and Trudy.

Despite being married, John and Trudy choose to continue to live in their separate homes, as they have always done before getting married. John has three children from a previous relationship who live with him in their home in Hamilton. Meanwhile, Trudy has one child and a cat who live with her in their home in Auckland. John's children go to school in Hamilton, while Trudy's child goes to school in Auckland. John runs a small business from Hamilton, while Trudy works in central Auckland. John's and Trudy's personal property is also kept separately in their respective separate homes.

Taking all facts into account, it can be said that John has chosen to make his home in Hamilton by reason of his family and personal relations in Hamilton, while Trudy has chosen to make her home in Auckland. As John and Trudy genuinely live separately in two different homes, John and Trudy can each have a separate excluded home. However, this can only be the case for three years, after which only one property will be the couple's excluded home.

20. There should be an anti-avoidance provision to stop people from artificially creating a situation where a couple can have two excluded homes.

Who can own an excluded home?

21. An excluded home should be a property owned separately or jointly by the person who uses it as a residence. An excluded home can also be:

- a property owned by a trust, if a person occupying the property mainly as their residence is:

- a settlor of the trust, or

- a beneficiary of the trust who becomes irrevocably entitled to the property or to the proceeds from the sale of the property as beneficiary income

- shares in a flat-owning company, if a person who owns the shares occupies the property mainly as their residence

- a property owned by an ordinary company or look-through company, if the person who owns the shares occupies the property mainly as their residence, or

- shares in a flat-owning company, or a property owned by an ordinary company or look-through company, where the shares in the flat-owning company, ordinary company or look-through company are owned by a trust and the person occupying the property mainly as their residence is:

- a settlor of the trust, or

- a beneficiary of the trust who becomes irrevocably entitled to the property or to the proceeds from the sale of the property as beneficiary income.

Example 12: Excluded homes in a family trust

The Hunia Family Trust was settled by Mr and Mrs Hunia. The Hunia Family Trust owns four residential properties. One of the properties is occupied by Mr and Mrs Hunia as their family home. This will be an excluded home.

The other three properties are each occupied as a main home by Mr and Mrs Hunia's three children, Ariki, Tui and Kauri and their families.

The trustees resolve to distribute the properties occupied by Ariki and Tui to Ariki and Tui. The disposal of these properties by the Hunia Family Trust will not give rise to tax because the properties will qualify as excluded homes.

The trustees resolve to sell the property occupied by Kauri and distribute the sale proceeds to Kauri as beneficiary income. The sale of the property will not give rise to tax because the property will also qualify as an excluded home.

Example 13: Property held by a family trust that is not an excluded home

The Jones Family Trust was settled by Mr and Mrs Jones. The Jones Family Trust owns a residential property in Dunedin. The Dunedin property is occupied by Mr and Mrs Jones' daughter as her home for four years while she attends university. The Dunedin property is then rented to a third party for one year before being sold. The Jones Family Trust reinvests the sale proceeds.

The Dunedin property will not qualify as an excluded home. It was not occupied by a beneficiary of the trust who became irrevocably entitled to the property or the proceeds of sale.

22. Only New Zealand tax residents (who are not treated under a double tax agreement as being non-resident) should be entitled to have an excluded home in New Zealand (subject to certain ‘change-of-use exceptions’, discussed further in Chapter 5).

Example 14: New Zealand property owned by a non-resident

Jonathan owns a property in Auckland, which he lived in for 10 years with his family. In 2018, Jonathan and his family moved to Melbourne and purchased a house there. Jonathan works primarily in Melbourne and his children attend school there. However, Jonathan retained his Auckland property, which he stays in regularly when he is in Auckland for business. The family also spend their holidays in the Auckland property from time to time.

Because Jonathan retained his Auckland property, which he continues to use, he will still be a New Zealand tax resident (because he has a permanent place of abode in New Zealand). However, because Jonathan and his family live in Melbourne, Jonathan will also be an Australian tax resident. Under the double tax agreement between Australia and New Zealand, Jonathan will be deemed to be a tax resident only of Australia, because his personal and economic relations are closer to Australia.

Because Jonathan is treated under the double tax agreement as not being a New Zealand tax resident, the Auckland property cannot be an excluded home.

Only one excluded home

23. A person, or a person and their family living with them, should only have one excluded home at any one point in time. If a person has two properties, they will need to determine which property is the one that is their excluded home.

Example 15: One excluded home

Karen and her husband Sione own a house in Wellington where they live with their two small children (ages 5 and 7). Karen and Sione both work in Wellington and the children go to school in Wellington. However, Karen often has to travel to Auckland for work, so the couple decides to buy an apartment in Auckland. The apartment is jointly owned in Karen and Sione's names.

Karen stays in the apartment two or three days each week when she is required to be in Auckland for work. The rest of the time Karen lives in Wellington with her family. Sometimes the family travels to Auckland for a long weekend or a holiday and stay in the Auckland apartment. The family spends approximately six weeks in total each year in the Auckland apartment together.

Although Karen and Sione own two properties, only the Wellington house can be their excluded home because that is where Karen and Sione have chosen to make their home by reason of their family or personal relations, or for other domestic or personal reasons and the family spends most of their time there.

24. If a person has more than one property that could satisfy the requirements to be an excluded home, i.e. that is a place that the person owns, where they choose to make their home by reason of family or personal relations or for other domestic or personal reasons, they should be required to make an election as to which property is their excluded home. The election should be made when the first property is sold. If a person elects that the first property sold was their excluded home, the second property should not be an excluded home for the same period.

Example 16: Election

Mark and Marijke own properties in Invercargill and Wanaka. They spend equal amounts of time in each property during the year and keep personal possessions in both properties. Both properties could be said to be Mark and Marijke's home.

In 2025, Mark and Marijke decide to sell their Invercargill property. At the time of sale they elect that the Invercargill property was their excluded home for the whole time it was owned. In 2035 Mark and Marijke sell their Wanaka property. The Wanaka property can only be Mark and Marijke's excluded home from 2025 to 2035 (i.e. the period after the Invercargill property was sold).

Exceptions

25. There should be two exceptions to the general rule that a person, or a person and their family living with them, can only have one excluded home.

26. Where a person, or a person and their family living with them, purchases a new home but has not yet sold their original home, both properties should be excluded homes for up to 12 months while the original home is held for sale. The original home must have been used as the person's excluded home and the person must have purchased the new home with the intention that it will be used as the person's excluded home going forward.

Example 17: Sale and purchase

Cath and Will own a property that they have occupied as their excluded home. They decide to move to another area. They find a new home, purchase it and move into it. However, it takes three months to sell their old home. While it is on the market, the old home is left vacant.

Cath and Will's old home and their new home will both be excluded homes for the three months they own both.

27. The same principle should also apply where a single person moves out of their excluded home into a rest home. The person's original home should remain an excluded home for up to 12 months. The original home can be rented while it is being held for sale.

28. A person, or a person and their family living with them, should also be able to have two excluded homes for up to 12 months when they purchase vacant land to build a new home. The vacant land must be purchased with the intention of building a home that will be the person's excluded home when it is completed and the other property must be occupied by the person as their current excluded home.

Example 18: Building a new home

Arena and Herangi have a home in central Wellington. They decide to purchase a vacant section in the outer suburbs and build a new home for themselves. It takes one year from the date of purchase of the vacant section for the new home to be built. During that time Arena and Herangi continue to live in their central Wellington home. Once the new home is completed, Arena and Herangi sell their central Wellington home and move into their new home.

Both properties can be treated as excluded homes for the 12 months that Arena and Herangi own both.

Example 19: Building over a longer period

Jason and Kim have a home that they have occupied for a number of years. They decide to purchase some vacant land, with the intention of building a new home for themselves. They hold the land for three years before they start to develop plans. Once they start to develop plans, it takes a further three years to complete the home. Once the new home is completed, Jason and Kim sell their old home and move into their new one.

Jason and Kim can treat both properties as their excluded home but only for a period of 12 months.

29. A person will not be entitled to have two excluded homes (as a result of the exceptions discussed in paragraphs 25 to 28) for more than 12 months. If a person holds both properties for more than 12 months there will be a deemed change of use of the original property from the date the use originally changed (discussed in Chapter 5).

Land under an excluded home

30. The excluded home should include the land under the house and the land around the house up to the lesser of 4,500m2 or the amount required for the reasonable occupation and enjoyment of the house. However, this land area allowance should be monitored and reduced if necessary.

31. Where the total area of the property is greater than 4,500m⊃;, or is not required for the reasonable occupation and enjoyment of the house, the gain on sale should be apportioned on a reasonable basis.

Example 20: Land under an excluded home

The Farmers own a 100-acre sheep farm. Approximately 4,000m2 of the land comprises the Farmers' house and gardens. The remainder of the property is devoted to business purposes.

Only the area of the house and gardens is part of the excluded home. When the Farmers sell the land, they obtain a valuation of the area comprising the house and gardens, compared to the rest of the property. The valuation confirms that the house and gardens make up approximately 15% of the value of the whole farm.

On that basis, only 15% of the total gain on sale can be allocated to the excluded home.

Partial use of an excluded home for income-earning purposes

32. Where a person uses part of their property for income-earning purposes, while they are also living in the property (e.g. where there is a home office, a room is used for Airbnb or where a person has flatmates), the person should have two options as to how the property should be taxed:

- provided the property is used more than 50% as the person's home, a person can choose to treat the entire property as their excluded home. However, the person will be denied any deductions for costs relating to the property, e.g. rates and interest, in relation to their income-earning use. The person will still be required to return their income from the income-earning use

- alternatively, if the person wants to take deductions relating to their income-earning use of the property, the person can choose to apportion their capital gain when they sell the property and pay tax on the portion that represents their income-earning use.

33. In determining the use of the property, it will be necessary to take into account both the floor area used for income earning versus private purposes and the time that the property is used for income-earning purposes.

34. The following examples illustrate how this will apply:

Example 21: Home office

Dinesh owns a five-bedroom house that he uses as a residence for himself and his family. He also runs a consulting business out of one room in his house. As the area of the house used for income-earning purposes is minor and the house is more than 50% used as a residence, Dinesh can choose that the entire property will be an excluded home. However, if Dinesh chooses this option, he will not be entitled to claim any deductions for expenses relating to the property against the income from his consulting business.

Example 22: Airbnb

Mary purchases a house, which she occupies as her main home. The house has two living areas, one of which has a small kitchenette. Mary decides to advertise the use of one of the bedrooms and the second living area with the small kitchenette (approximately 33% of the total floor area of her house) on Airbnb. Mary has paying guests staying in her house for an average of 50 days each year. Mary uses those areas for her own private use at other times of the year.

Both the area used (33% of the floor area) and time the area was used for income-earning purposes (an average of 50 days a year) amount to less than 50% income-earning use of the property. Therefore, Mary can choose that the entire property will be an excluded home. However, if Mary chooses this option, she will not be entitled to claim any deductions for the expenses relating to the property against her Airbnb income.

Example 23: Flatmates

Thomas owns a four-bedroom house. To assist with paying his mortgage, Thomas rents out two of the bedrooms (approximately 25% of the floor area of the house). He also shares the use of the living areas (33% of the floor area of the house) with his flatmates.

In this scenario, the living areas are being used simultaneously for both private purposes, i.e. this is part of Thomas' residence, and for income-earning purposes (as part of the area that is being rented out).

The property is more than 50% used by Thomas as his residence. He has exclusive access to two of the four bedrooms and shared access to the living areas. Therefore, Thomas could choose to treat the entire property as an excluded home. However, Thomas wants to claim deductions for his expenses relating to the property, particularly for his interest expense, against his income from his flatmates' rent. Therefore, when he sells, Thomas will need to pay tax on the portion of the property that was used for income-earning purposes.

Thomas will be required to apportion the net sale proceeds based on the floor area devoted entirely to income-earning use, i.e. 25% of the total floor space. Thomas will also be required to make an apportionment to account for the partial income-earning use of the living areas. This would be based on 50% of the gain attributed to that 33% of the house. Inland Revenue guidance states that expenditure relating to common areas can be apportioned as 50% private and 50% deductible. A similar principle could be applied to apportioning net sale proceeds under a new tax on capital gains.

This would result in approximately 41.5% of the gain on sale being taxable (25% + (33% × 50%)). For example, if the property was sold for a $100,000 gain the calculation would be as follows:

- (100,000 × 25%) + ($100,000 × 33%) × 50% = $41,500 taxable capital gain

Example 24: Boarders

Moana and Tama own a property they use as their home. They own the property for 10 years. For two of those years Moana and Tama have a Japanese exchange student, Aiko, living in their home as a boarder. They are provided money from the school for their boarding services.

The property is used more than 50% as Moana and Tama's residence. Therefore, Moana and Tama could choose to treat the entire property as their excluded home. However, if Moana and Tama decide to do this, they will not be entitled to any deductions for expenses relating to the property against the board income they received.

Moana and Tama will have to choose between two options:

- treat the entire property as their excluded home. In this case determination DET 05/03: Standard-Cost Household Service for Boarding Service Providers will not apply as no deductions will be available. Moana and Tama will have to return the board income as taxable income

- choose to apply DET 05/03 and not return their board income but apportion the capital gain when they sell their home and pay tax on the portion that relates to the income-earning use based on area and time.

35. When a property is used more than 50% for income-earning purposes, e.g. as a boarding house, or where a person has a four bedroom house with three flatmates, a person will be entitled to apportion the capital gain on sale and treat the part of the property used as a residence as an excluded home.

Example 25: Part of a larger building used for private purposes

Ruby owns a five-bedroom property that she uses to run a bed and breakfast business. Ruby uses four of the bedrooms and most of the living areas for the bed and breakfast business. However, Ruby occupies one of the bedrooms and a small living area and bathroom attached to that bedroom, as her residence - approximately 20% of the floor area of the property.

The 20% of the property used as Ruby's residence can be treated as an excluded home and Ruby would only have to pay tax on 80% of the gain on sale.

High-value homes

36. In the Interim Report, the Group raised the possibility of applying a limit on the value of an excluded home for higher-value homes. This option is raised as a potential option for mitigating the ‘mansion effect', where people invest more capital in their main home where it can generate untaxed capital gains.

37. The Group considers this to be outside its Terms of Reference and so has not considered it further. However, the Group recommends that this option be considered by the Government.

Personal-use assets

38. The extension of the taxation of capital gains should not apply to personal-use assets held by individuals and by trusts where the assets are available for the personal use of beneficiaries. This would include cars, boats and other household durables. These types of assets generally decline in value and the loss on sale represents the cost of having private, non-taxed, consumption benefits. Taxing these types of assets would also significantly increase the number of taxpayers impacted by an extension of the taxation of capital gains. However, this exclusion would not apply to land held for private purposes.

39. Personal-use assets will include intangible property not owned or created for business purposes. This would include intangible property, such as rights to benefit under a trust or will, personal insurance policies and occupation rights relating to a retirement village.

40. This exclusion would also apply to jewellery, fine art, taonga and other collectables (rare coins, vintage cars etc). The Group accepts that these assets are distinguishable from other types of personal-use assets because they are often purchased as investments and are usually expected to increase in value. Excluding these types of assets from an extension of the taxation of capital gains may incentivise investment in such assets over more productive assets. However, at this time, the Group proposes to exclude these assets for reasons of simplicity and compliance cost reduction. This concession should be monitored and, if necessary, revisited in the future, either entirely or by tax applying over a certain threshold.

Example 26: Personal-use assets

Penny owns an artwork. The artwork will be a personal-use asset and will not be subject to an extension of the taxation of capital gains.

41. As noted below (from paragraph 46) if personal-use assets are revenue account property they will continue to be subject to tax.

Assets and entities under Te Ture Whenua Māori Act 1993

42. Māori Freehold Land (as defined in Te Ture Whenua Māori Act 1993) is a type of collectively owned land that comprises approximately 1.4 million hectares (5%) of the total land mass of New Zealand (Ministry of Justice, 2017). It is a place of cultural significance through which Māori connect with their whānau through whakapapa. Māori Freehold Land is typically owned by individual Māori who have shares together as tenants in common. However, unlike for other land in New Zealand, Te Ture Whenua Māori Act sets strict rules applying to Māori Freehold Land that are intended to keep such land in Māori control. In practice, this means that Māori Freehold Land is rarely sold.

43. Due to the distinct context of Māori Freehold Land, the Group considers that Māori Freehold Land and interests in Māori Freehold Land held via an entity governed by Te Ture Whenua Māori Act (e.g. an ahu whenua trust or Māori incorporation) merit specific treatment under an extension to the taxation of capital gains. This could take the form of an exclusion (either generally, or only to the extent that proceeds from the sale of part of the land is reinvested in other Māori Freehold Land), or it could be built into the rollover principles discussed below in Chapter 3. The Government should engage with Māori in order to determine the specific treatment to be used.

44. The Group has not made a specific decision on the treatment of interests in such Māori entities (i.e. beneficial interests relating to individuals) that own assets other than Māori Freehold Land. This issue should be explored further through consultation as part of the generic tax policy process. In a practical sense, the ownership base of a Māori authority (being one of whakapapa or birth right) will generally increase with population growth, with no corresponding new investment by new owners. As a result, Māori authorities tend to experience perpetual shareholder dilution and so any capital gains made on ownership interests are likely to be non-existent or very small.

45. Assets and entities under Te Ture Whenua Māori Act will have ordinary rollover treatment under the rollover principles discussed in Chapter 3 below, except for some circumstances for which specific treatment is warranted. See the section Māori collectively owned assets from paragraph 24.

Revenue account property

46. As mentioned above, under the current law, a capital gain from the sale of some assets is already subject to tax. Those assets are referred to as ‘revenue account property', which is defined in the Income Tax Act 2007 as:

- property that is trading stock of the person, or

- property that, if disposed of for valuable consideration, would give rise to income under the Act (with some exceptions).

47. Revenue account property includes property that was acquired with a purpose of disposing of it.

48. Assets that are ‘revenue account property', including personal-use assets, will continue to be taxed under the current law. However, where loss ring-fencing is proposed for a type of property (discussed in Chapter 4) the same rules should also apply if that type of property is held as revenue account property (except for trading stock).

Summary

49. The following table summarises what are included assets and what are excluded assets.

Included assets

- Land and improvements to land (not including the excluded home)

- Shares not including shares in foreign companies that are already subject to the fair dividend rate (FDR) method, non-portfolio interests in foreign companies (i.e. interests of 10% or more) that are taxed under the foreign investment fund (FIF) rules and shares in non-attributing controlled foreign companies (CFCs)

- Intangible property owned or created for business purposes.

- Other business assets, including depreciable property but not including trading stock.

Excluded assets

- The excluded home.

- Personal-use assets (including intangible property that is a personal-use asset)

Notes

- [1] Note that the tax treatment for shares in foreign companies that are already subject to the fair dividend rate method under the foreign investment fund rules, and the tax treatment for shares in non-attributing controlled foreign companies and non-portfolio (i.e. holdings of more than 10%) foreign investment funds held by companies, will not materially change.

- [2] A flat-owning company is one where every shareholder is entitled to use of a property owned by the company and whose only significant assets are those properties and funds reserved for meeting costs.

- [3] In this context, the Group notes there have been instances where a right has been provided in relation to particular Māori taonga, as part of a Treaty settlement. For example, the Haka Ka Mate Act 2014 requires those performing the haka in commercial situations to include a prominent statement that Te Rauparaha was the composer of Ka Mate and a chief of Ngāti Toa Rangatira. In practice, the Group expects the likelihood of Māori selling such rights would be rare.

- [4] See Chapter 4 for a brief discussion on how an extension of the taxation of capital gains will apply to depreciable property.

3 When to tax?

1. Tax should be imposed on a realisation basis in most cases. Under a realisation basis, taxpayers are taxed on the increase in value when they dispose of their included assets.

When is an asset disposed of?

2. A disposal of an included asset (also referred to as a realisation event) will usually involve a transfer of legal ownership. The typical case would be a sale for consideration, either in cash or in kind, e.g. a barter transaction or asset trade. Realisation will also arise despite payment of the consideration being deferred for a shorter or longer period and where assets are transferred for no consideration, e.g. transfers on death, gifts, transfers of relationship property and settlements on/distributions from trusts.

3. Consistent with current law, assets will also be treated as realised where they are destroyed or scrapped and when they are abandoned or no longer available for use.

When realisation events will be deemed to occur

Change of use

4. A realisation event should be deemed to occur when a person changes the use of their asset so that it ceases to be an included asset. For example, this may occur when a person who owns a rental property starts using it as their excluded home. Rules for taxing this deemed realisation are described in Chapter 5.

Migration

5. A realisation event should be deemed to occur when a New Zealand resident, who owns certain included assets, migrates to another country and removes those assets from the tax base. Detailed rules for this deemed realisation are discussed below in Chapter 5.

When realisation events will be ignored

6. There are, however, some situations where a realisation event should be ignored. This treatment recognises that, in some situations, it is fairer or more efficient not to tax the resulting gain or loss, despite the asset having been realised (in accordance with the principles discussed in Chapter 5 of Volume I). This treatment is referred to as a ‘rollover'.

7. Under rollover treatment, the taxation of a capital gain or deduction of a capital loss is deferred until there is a later realisation event that is not eligible for rollover treatment. Instead of taxing the gain when the asset is initially realised, the cost base, i.e. the cost that a person pays to acquire and improve an asset, is rolled over into a replacement asset or to the new owner of the asset, who is taxed on the entire gain when they realise the asset.

Example 27: Rollover treatment

Alison buys a holiday home for $500,000. When Alison dies, she leaves the holiday home, worth $700,000, to her children. The children sell it 5 years later for $950,000.

If the transfer of the holiday home to Alison's children is treated as a realisation event that is not eligible for rollover treatment:

- Alison will have $200,000 of taxable income at the time of her death, which will be returned by her executor/administrator

- Alison's children will have taxable income of $250,000 when they sell the holiday home 5 years later.

If the transfer is eligible for rollover treatment:

- Alison will be treated as having no taxable income from the holiday home on her death

- Alison's children will have taxable income of $450,000 when they sell the holiday home five years later.

Life events (death, gifting and separation)

8. The excluded home, art, vehicles and other personal-use assets should not be subject to an extension of the taxation of capital gains and can be gifted or inherited with no tax implications. Cash, bonds and term deposits are outside the scope of the new rules, as they are already fully taxed. Therefore, the new rules will only apply to included assets, such as rental properties, other land and shares.

9. Where the excluded home is transferred on death, and the beneficiary uses it as their excluded home, it will continue to be an excluded asset for the beneficiary. If the beneficiary uses it for any other purpose it will become an included asset for the beneficiary from the time it is transferred to them, with the cost base being the market value at the time of transfer.

10. Rollover should be provided for all included assets that are transferred to a person's spouse, civil union partner or de facto partner, e.g. as a gift or when the person dies. This is because the couple would already be considered to have shared ownership interests in many of these assets. Rollover should also apply where included assets are transferred as part of a relationship property settlement (i.e. when a marriage, civil union or de facto relationship is dissolved).

11. Where included assets are transferred on death of the owner to persons other than the person's spouse, civil union partner or de facto partner, regardless of the relationship between the person and the recipient, the Group has identified a range of options to be considered further through the generic tax policy process.

12. Where included assets are transferred on the death of a person, the following two options should be considered:

- providing rollover only for transfers of certain illiquid assets, i.e. assets not easily realised within an ongoing business (e.g. unlisted shares, active business premises, intangible property and interests in Māori Freehold Land), or

- providing rollover for all transfers of included assets on death.

13. Providing rollover for illiquid assets on death recognises that these types of assets are difficult and costly to value and are hard to sell or borrow against to fund a tax liability. However, limiting rollover on death to illiquid assets could mean added complexity, because rules would be needed to determine which types of assets would qualify and could create investment biases or horizontal equity issues. Also, in a sense, inheritors have an existing interest in the property through the will or intestacy law.

Example 28: Rollover on death

Wiremu owns an excluded home, a rental property and 100% of the shares in his plumbing business, Pipes Limited. Wiremu dies and leaves the excluded home and rental property to his son and the shares in Pipes Limited to his daughter, who has been working in the business.

As Wiremu's excluded home is excluded from the tax it is not taxed on his death (it would also not be taxed if Wiremu had gifted or sold it). If rollover is limited to transfers of illiquid assets, then the transfer of the shares in Pipes Limited would be ignored and Wiremu's daughter would inherit Wiremu's cost base in the shares. However, because a rental property is not an illiquid asset, the transfer of the rental property would be a realisation event. Wiremu's estate would be required to pay tax on any capital gain (based on a transfer for market value) and Wiremu's son would have a new cost base for the rental property equal to the market value of the rental property at the time of transfer.

If rollover is extended to all transfers of included assets on death, the transfers of both the shares in Pipes Limited and the rental property would be ignored and Wiremu's daughter and son would respectively inherit Wiremu's cost base in the shares and rental property.

14. The Group's preferred view is that rollover should be provided for all transfers of included assets on death.

15. Where included assets are transferred as a gift while a person is still alive, the following two options should be considered:

- aligning rollover treatment with that provided for transfers of included assets on death (see options above), or

- providing no rollover (other than for gifts to the person's marriage, civil union or de facto partner as discussed above).

16. There is some merit in aligning the treatment for transfers by gift with the treatment for transfers on death. This is because any distinction in the tax treatment could lead to unnecessarily complex tax planning and economic inefficiencies, such as creating a lock-in bias to retain assets until death. However, a key difference between gifts and transfers on death is that death is not typically an event the taxpayer controls, whereas gifting is. There is a concern that allowing rollover for all gifts to any person (including trusts) at any time gives rise to integrity concerns.

17. The Group's preferred view is that no rollover should be provided for gifts of included assets (other than for gifts to the person's marriage, civil union or de facto partner). This is how most countries treat gifts for their taxation of capital gains.

18. However, where gifts of included assets are made to donee organisations (typically charities) there should be some kind of relief, consistent with the current incentives provided for gifts of money. Under current law, a donation of money to a charity gives rise to a refundable donation tax credit for the person who made the donation. Where included assets are donated to a donee organisation, either:

- the donation should be treated as a realisation event but the person making the donation should be entitled to a donation tax credit for the donation, or

- the donation should be ignored for tax purposes, with no tax payable on the capital gain and no donation tax credit provided.

19. The Group's preferred view is that the donation should be ignored for tax purposes. This is more consistent with current donation tax credit rules.

Involuntary events (Insurance and Crown acquisition)

20. Rollover treatment should also apply to certain events where a person involuntarily realises an asset and reinvests the proceeds in a similar replacement asset (within a limited period of time). In these circumstances, taxing the realisation may prevent the person from being able to replace the asset they involuntarily lost. These events are:

- where an asset is destroyed by a natural disaster or similar event that is outside of the owner's control and insurance proceeds or other compensation is received, and

- compulsory acquisition of land by the Crown, e.g. under the Public Works Act 1981.

Example 29: Rollover for insurance proceeds

A taxpayer owns a hotel building that is torn down following earthquake damage. The building is insured for replacement cost. The insurance company pays the building owner insurance proceeds of $3 million, which is greater than the taxpayer's $1 million cost base in the building. The taxpayer uses the proceeds to acquire a similar replacement building for $3 million.

If there is no rollover, the taxpayer would be taxed on the $2 million gain.

If rollover treatment applies, the taxpayer would not be taxed on receipt of the insurance proceeds. However, the replacement building would assume the original building's cost base of $1 million. If the taxpayer subsequently sells the replacement building for $5 million they would be taxed on a gain of $4 million.

Business restructures with no change in ownership in substance

21. Rollover treatment should be provided for business transactions that result in a realisation of assets but no change in ownership in substance. Such transactions include:

- switching between trading structures (e.g. a sole trader decides to incorporate a company and put their business assets into the company in exchange for 100% of the shares)

- transfers within a wholly-owned group

- qualifying amalgamations

- de-mergers (when a company gets split into multiple companies and the owners of the original company receive shares in the new companies)

- scrip-for-scrip exchanges (a takeover or merger where a shareholder receives shares in the new company in return for shares in their old company).

22. Australia has a set of rollover rules for de-merger and scrip-for-scrip exchanges. Owing to the level of Trans-Tasman trading, consideration should be given to whether these rules should be adopted in New Zealand.

23. In the New Zealand context, this rollover principle should accommodate some Māori collectively owned structures and transactions. In particular, asset transfers from iwi to associated hapū, marae and associated entities (and from hapū or marae to iwi or associated entities) and inter-hapū transactions within the same iwi should qualify for rollover. For example, in the Treaty settlement context, assets are transferred from the Crown to the iwi's post-settlement governance entity (consistent with the Crown's ‘large natural groupings' policy) and that entity may later transfer specific assets to hapū or marae (or associated entities on their behalf) that are the customary owner. Tax should not be a barrier to the transfer of such assets within the iwi.

Māori collectively owned assets

24. The Group recognises that taxation of capital gains could create an impediment to a Māori organisation's ability to regain ownership over land lost as a result of historical Crown action. Accordingly, rollover should be provided for transactions relating to recovery by Māori authorities of such land.

25. For example, under Treaty settlement, the Crown can only include in redress land the Crown owns and is ready to dispose of at the time of settlement. When ancestral land is made available by the Crown or becomes available on the open market subsequent to settlement, Māori organisations may need to realise gains by selling land or other assets acquired through their settlement to purchase that ancestral land. Without a rollover rule in this circumstance, a Māori organisation would be subject to tax owing to the arbitrary fact that its preferred ancestral land was not available for the Crown to include in original Treaty settlement redress.

26. In the Treaty settlement context, iwi may not immediately develop the strategic and commercial capabilities needed to align assets with their strategic objectives. The Group notes the Crown's policy of tax indemnities for the transfer of assets from the Crown to iwi under a Treaty settlement and considers that time-limited relief on realised capital gains from settlement assets is also merited.

27. The specific design of rollover rules applicable to Māori collectively owned assets should be developed through further engagement with Māori to ensure the rules achieve the intended policy.

Small business rollover

28. There should be no general rollover treatment for business assets. However, rollover should be provided for small businesses that sell qualifying business assets and reinvest the proceeds in replacement business assets. This is intended to mitigate lock-in for small businesses that may need to upgrade their premises or other business assets as they expand and grow.

29. A small business could be defined as a business with annual turnover of less than $5 million (on an average basis considering the previous five years). A qualifying business asset could be defined as business premises (land and buildings) and intangible property, such as goodwill and intellectual property, that are used to conduct an active business. Shares and leased real property, i.e. commercial offices and residential accommodation that are rented out to a third party, would be excluded.

30. The gains on qualifying business assets would be rolled over to the extent that they were reinvested in replacement active assets within a certain time period, e.g. 12 months. For example, a farmer selling part of their farm and using the proceeds to buy a commercial premises from which they will operate a farm machinery business.

Example 30: Small business rollover

Bakery Limited runs a small bakery out of premises that it owns. The annual turnover for the business is approximately $500,000. Bakery Limited wants to expand but cannot do so in its current premises. Bakery Limited identifies new, larger premises in a similar area. It sells its old premises and uses the sale proceeds to purchase the new premises.

Bakery Limited is a small business. Because it re-invested the proceeds from the sale of its old premises in a new premises it will qualify for the small business rollover treatment, and will not have to pay tax on the gain in value from the sale of its old premises. However, the new premises would assume the old premises' cost base (plus any additional consideration paid for the new premises over and above the proceeds from the sale of the old premises).

Sale of a closely held business upon retirement

31. The Group understands that many business owners fund their retirements by selling their businesses. Another major form of retirement savings is KiwiSaver schemes. In Chapter 5 of Volume I of this report, the Group recommended setting the prescribed investor rates for KiwiSaver schemes at five percentage points lower than the savers' marginal tax rate, so the KiwiSaver tax rates would be 5.5%, 12.5% and 28%.

32. The Group recommends providing a one-off concession by extending these lower KiwiSaver tax rates to the first $500,000 of capital gains made by business owners who sell a closely held active business they have owned for a certain period of time (e.g. 15 years) to retire once they reach retirement age (e.g. 60 years or older). This measure could also potentially apply to younger business owners to the extent that the capital gain they made from selling their business is reinvested into a KiwiSaver scheme.

Example 31: Closely held business on retirement

Gary owns a building business, which he has built up over the past 30 years. When he turns 60, Gary decides to sell the business to one of his senior employees. He sells the business for a capital gain of $1 million. Gary qualifies for the concession for closely held active businesses sold on retirement. Therefore, $500,000 of the capital gain qualifies to be taxed at the lower KiwiSaver tax rates.

If Gary had other income of $70,000 for the income year, this would mean that $500,000 of the capital gain would be taxed at 28% and $500,000 at 33%.

4 How to tax?

General principles

1. Capital gains should be taxed in the same way as any other income. This means capital gains arising from the realisation of included assets will be taxed at a person's marginal tax rate.

Example 32: Application of marginal tax rates

Moana earns $48,000 in wages in a tax year. In the same year, Moana sells some shares and receives a capital gain of $10,000. Her total income this year is $58,000.

Moana's tax liability will be calculated as follows:

$14,000 @ 10.5% $1,470

$34,000 @ 17.5% $5,950

$10,000 @ 30% $3,000

TOTAL TAX $10,420

2. As discussed in Chapter 5 of Volume I, the Group does not recommend that the tax rate for capital gains should be subject to any discount. The Group also does not recommend that income derived from realising included assets should be adjusted for inflation.

Calculation of taxable income

3. Taxable income derived from realising an included asset should be calculated in the same way as other income. In other words, taxable income is calculated by deducting total expenditure from total income, subject to specific timing rules.

Income

4. As discussed in Chapter 3 above, income from included assets will generally be taxed on realisation, i.e. when the asset is sold or otherwise disposed of. The income will be the total sale proceeds or, if the asset is transferred for less than market value (e.g. as a gift), the market value of the included asset at the time of transfer.

Expenditure

5. As a general proposition, expenditure incurred in acquiring an included asset will be deductible at the time of sale. Similarly, costs incurred after acquisition on making improvements[5] to the asset will also be deductible from the sale proceeds.

Example 33: Calculating net income

Midori owns a holiday home that she purchased for $350,000. After purchasing the home, Midori spent $5,000 on updating the bathroom. Five years later Midori sells the holiday home for $500,000.

In the year that Midori sells the holiday home she will have income of $500,000 and will be allowed a deduction for the acquisition and improvement costs of $355,000, giving her net income of $145,000.

Holding costs

6. Where income is derived from the land, e.g. the land is used as a rental property, costs incurred in connection with holding the land will usually be deductible in the year they are incurred. This includes costs such as interest, rates, insurance and repairs and maintenance expenditure. This treatment should continue for included assets.

Example 34: Holding costs

Jonathan owns a rental property. In the 2024 income year, he pays rates of $2,000, interest of $10,000 and insurance of $1,000 in relation to the property.

Jonathan will be allowed to deduct the rates, interest and insurance expenses from his rental income for the 2024 income year. These costs will not be added to the cost base of the rental property.

7. Current law will continue to be used to identify costs that are costs of acquiring or improving an asset that can reduce a capital gain, versus those holding and other routine costs, e.g. repairs and maintenance expenditure, relating to included assets that are deductible in the year they are incurred.

Land used for private purposes

8. All land, other than the excluded home, should be subject to tax on sale, even if held for private purposes, e.g. as a second home. Expenditure incurred in acquiring or improving land held for private purposes should be deductible on sale. These are costs traditionally considered to be on capital account. However, where land is held for private purposes, costs incurred in connection with holding the land (e.g. interest, rates, insurance and repairs and maintenance costs) should not be deductible because this represents private consumption. These are costs traditionally considered to be on revenue account if gains on sale would have been taxable.

Depreciation

9. Under current law, depreciation deductions are allowed each year for assets that are used to derive assessable income and that are expected to decline in value (‘depreciable property'). Where an included asset is depreciable property, depreciation deductions should continue to be allowed. On sale of the asset, the deduction allowed will be the total acquisition and improvement expenditure that has not previously been deducted by way of depreciation. For most depreciable property, this result is the same as the present ‘loss-on- sale' rules, however, losses on buildings (not currently deductible) should also be able to be deducted.

Example 35: Depreciable property

Tai has developed software that he uses in his IT business. His development costs were $200,000. He used the software in his business for one year, over which time he claimed $100,000 of depreciation deductions. He then sold the software for $250,000.

In the year of sale, Tai will be taxed on $100,000 of depreciation recovery income (as is the case under current rules) and $50,000 of capital gain ($250,000 - $200,000).

Specific rules

10. There are a number of specific rules in the tax legislation that allow deductions for costs of acquiring or developing specific assets over different periods (e.g. petroleum mining rules). Those rules should be reviewed as part of the generic tax policy process to determine whether they can be rationalised in light of an extension of the taxation of capital gains.

Entering the tax base

11. Where assets already owned by a person enter the tax base, the cost base of those assets for calculating the capital gain on sale will be the value of the assets on the date they entered the base, rather than their original cost. This will occur:

- when the rules for taxing more capital gains come into force (Valuation Day)

- when a person changes the use of their assets so that they become included assets (e.g. where a person starts using their excluded home as a rental property), and

- when a person migrates to New Zealand, bringing included assets with them.

12. Proposed rules for determining the value of assets in these situations are discussed in Chapter 5.

Cash flow assumptions

13. In the case of fungible assets (e.g. shares) where a holding can be acquired or disposed of in several transactions, identifying the cost of a specific item requires assumptions about the identity of the item sold (referred to as a cash flow assumption).

14. In the Interim Report, the Group identified some cash flow assumptions (e.g. first in first out, last in last out or average weighted cost) and concluded that further consideration needed to be given to which of those assumptions should be applied for determining the cost of fungible assets if capital gains are taxed more comprehensively. This issue should be considered further as part of the generic tax policy process.

Treatment of losses

Losses generally

15. Where the income from disposing of a capital asset is less than the acquisition and improvement costs relating to that asset, a loss will arise. Consistent with the view that capital gains should be taxed in the same way as other income, generally, losses arising from the disposal of capital assets should be able to be offset against other taxable income.

Example 36: General loss ring-fencing

Kim earns a $50,000 salary each year. She buys a rental property for $400,000. Kim later discovers that the rental property has weathertightness issues and its market value has declined to $370,000. Kim decides to cut her losses and sells the rental property for $370,000, resulting in a $30,000 loss.

Kim should be allowed to use the $30,000 loss to offset part of her $50,000 salary income, so that her net taxable income for the year is only $20,000 (being $50,000 - $30,000).

If there was general loss ring-fencing, Kim would only be allowed to use her $30,000 loss to offset against capital gains and not against her salary income. Instead, she would have to carry forward that loss until she derives a capital gain. If she never derives a capital gain, she will not be able to use that loss at all.

16. However, the Group recognises that allowing capital losses to be deducted from other income comes with risk. Therefore, the Group recommends there should also be some cases where losses cannot be offset against other income (i.e. some losses should be ring-fenced, so they can only be offset against gains from other included assets).

17. In the Interim Report the Group recommended that losses on portfolio listed shares and derivatives be ring-fenced to other included assets. This principle should be extended further to any asset where costs to trade are low and economic exposure to the particular asset can easily be regained after crystallising the loss (and which are not already taxed as financial arrangements), such as precious metals or cryptocurrencies.

Example 37: Loss ring-fencing on portfolio listed shares

Sierra directly holds shares in two NZX-listed companies, Alpha Limited and Bravo Limited.

Her Alpha Limited shares have a cost base of $100 and a market value of $120 at the end of the current income year.

Her Bravo Limited shares have a cost base of $100 and a market value of $70 at the end of the current income year.

If losses on portfolio-listed shares were not ring-fenced, Sierra would have an incentive to sell her shares in Bravo Limited before the end of the current income year. She could then repurchase Bravo Limited's shares at the start of the next income year for a similar price. Sierra's economic position would be materially unchanged but she would have been able to crystallise a loss of $30, which she could then use against her other income.

If losses on portfolio-listed shares are ring-fenced, Sierra would only be able to use the $30 loss from the sale of Bravo Limited's shares against gains from other included assets. Her incentive to bring forward the losses from the Bravo Limited shares is therefore greatly reduced.

18. Losses should also be ring-fenced in the following situations:

- where the cost base or deemed sale price of an asset is determined using a valuation method instead of an arm's-length price (for example, on Valuation Day discussed in Chapter 5)

- transactions between associated persons

- situations where taxpayers can choose to apply rollover treatment to gains but not to losses.

19. However, loss ring-fencing is only one possible option for addressing these integrity risks. The Group recommends that further consideration be given through the generic tax policy process to all the options for addressing these integrity risks.

Land used for private purposes

20. Where land, and the buildings on it, is used for private purposes, no losses can be claimed on sale. This is on the basis that such a loss will generally represent private consumption.

Administration

21. The Group acknowledges that taxing more capital gains will increase the record-keeping and compliance costs for taxpayers, particularly for business taxpayers. Further consideration should be given through the generic tax policy process to options for reducing this impact and making tax collection and payment easier. This could include Inland Revenue providing calculators and other guidance to assist taxpayers.

22. Capital gains should be returned in a person's ordinary income tax return in the same way as other income. Whether a person would have to ‘file' a tax return would depend on the way in which taxable capital gains are treated administratively.

23. Different asset classes might lend themselves to different administrative treatments. In addition, the Group recognises that some realisation events will not give rise to any cash, and collection rules may need to recognise this.

24. In the Interim Report, the Group noted that it could be possible to make use of withholding taxes and third-party information reporting to assist with tax collection. Withholding taxes and third-party information reporting regimes generally involve a trade-off between reducing the compliance burden on the person earning the income and increasing the compliance burden on the payer or reporter. The aim is to reduce compliance costs in the system overall. Requiring a third party to provide information about a transaction, or to withhold tax generally, mitigates the risk of lower compliance rates, which could arise if the payee was required to report their own income.

25. However, increasing information or withholding requirements would increase the obligations on third parties, which should not be underestimated. The Group is very aware of the cumulative effect of recent law changes that have increased the obligations on businesses. In addition, withholding obligations, especially if the rate is too high, can raise obstacles for liquidity. That is especially important to equity markets. Therefore, the Group believes it is important that consultation is undertaken with affected or interested parties before recommendations are made as to how withholding or information provision systems might work in practice. The Group sees this consultation particularly focusing on those who may potentially be asked to provide information or withhold tax to ensure that the impact on those parties can be fully understood. This consultation should focus on the compliance costs that could be imposed on those who would have to withhold tax and how those costs could be minimised.

26. To assist with information provision more generally, information about the value of all assets on Valuation Day should be filed with Inland Revenue within five years and information about increases in the cost base of assets should be filed in the year when those cost are incurred. This will assist taxpayers with accurate record keeping. Taxpayers should disclose to Inland Revenue when they have made use of a rollover concession. All taxpayers should also be required to disclose their IRD numbers at the time of all land purchases and sales.

27. Capital gains should be included in provisional tax calculations in the same way as other income. In some cases, the impact on provisional tax payments of one-off types of income, such as capital gains, has been reduced through recent changes to ensure that most taxpayers will not pay use-of-money interest until their final instalment of provisional tax which is well after the end of the year the income is derived.

Example 38: Provisional tax — standard method

Harris Hoovers Limited is a vacuum sales company that has been in business for 40 years and owns its premises.

Harris Hoovers Limited is a provisional taxpayer that, owing to the steady nature of its income growth, uses the standard method for provisional tax (also known as the uplift method). In the 2024 tax year, Harris Hoovers Limited has residual income tax of $230,000. It has filed its income tax return for the 2024 return prior to its first instalment of provisional tax for the 2025 year. Its first instalment is therefore based on 105% of $230,000. Its instalment is one-third of $241,500 or $80,500. Harris Hoovers Limited also makes its second instalment of provisional tax on the same standard basis and makes another payment of $80,500 on the date of its second instalment.

Prior to Harris Hoovers Limited's third provisional tax instalment date, Laura, the current owner, decides that owing to the surging property market she would be better off selling the building and leasing another premises more suited to the current business needs. Harris Hoovers Limited sells the premises and makes a $700,000 capital gain in the 2025 tax year.

When paying its final provisional tax instalment Harris Hoovers Limited factors in the tax on the capital gain and increases the provisional tax instalment amount by $196,000 making a total payment of $276,500.

After year end Harris Hoovers Limited completes its tax return for the 2025 year. It calculates its tax liability for the year to be $462,500. That is represented by the tax on the capital gain on $196,000 and normal business profits of $266,500. As Harris Hoovers Limited has underpaid its tax for the year it will be subject to use-of-money interest, however, because Harris Hoovers Limited made its first two standard instalments on time and in full it will only be subject to use-of-money interest from the date of the final instalment of provisional tax on the underpayment of $25,000.

In calculating its 2026 provisional tax Harris Hoovers Limited decides to estimate its provisional tax. Because Harris Hoover Limited's income for the 2025 income year included the capital gain, using the standard method, and paying based on 105% of the 2025 residual income tax, would result in an overpayment as it is not likely to make any further capital gains.

Example 39: Provisional tax - estimate method

Libby is an accountant. In the 2031 income year she earns a salary of $80,000, which has pay as you earn (PAYE) deducted. Libby owns a rental property, which she purchased in 2025 for $600,000. In July 2030, Libby sells her rental property for $800,000.

Libby has made a $200,000 capital gain from selling her rental property, which will be taxed at 33% (Libby is already on the top marginal tax rate with her $80,000 salary). Libby already pays provisional tax on her rental income because her residual income tax liability is more than $2,500.

Libby estimates her provisional tax. She will now also be required to pay an additional $66,000 of provisional tax. Libby will be required to pay one third of the tax due on each instalment date, being 28 August 2030, 15 January 2031 and 7 May 2031. If Libby does not pay the correct amount of tax on each instalment date, use-of-money interest will be imposed.

Social policy

28. Current rules for some social policy schemes refer to a person's ‘income' under the Income Tax Act 2007 when calculating a person's entitlements and obligations (e.g. a person's Working for Families tax credits entitlement, student loan repayment obligation or child support calculated under the formula assessment). Income for this purpose currently includes some capital gains, e.g. capital gains arising from the sale of land that is subject to the bright-line test.

29. Capital gains should be treated as ordinary income. This means that capital gains should be included in the calculations for social policy schemes that rely on income under the Income Tax Act 2007 for the calculations. There is no obvious reason for excluding capital gains in these cases.

30. The Group also notes that revenue losses are currently excluded from the calculations. [6] Allowing capital losses to affect entitlements and obligations would be a departure from the existing rules that ignore losses. Consequently, for the same reasons that revenue losses are currently ignored, capital losses should also be ignored.

Notes

- [5] Not including holding costs (see paragraph 6).

- [6] With the exception of the child support formula assessment that does not currently ignore revenue losses. However, the Group notes the previous Government proposed more closely aligning the definition of income for child support purposes to that which is used for Working for Families tax credits and determining student loan repayments. This would include disregarding losses for the calculation in the formula assessment.

5 Transitional rules

Introduction

1. This Chapter considers the rules that should apply where assets already owned by a person enter or exit the tax base. This will occur when:

- the rules for taxing more capital gains come into force (Valuation Day)

- a person changes the use of their assets so that they become included assets, e.g. where a person starts using their excluded home as a rental property, or stop being included assets, e.g. where a car used for business purposes changes to a personal-use asset, and

- a person migrates to or from New Zealand, bringing included assets with them.

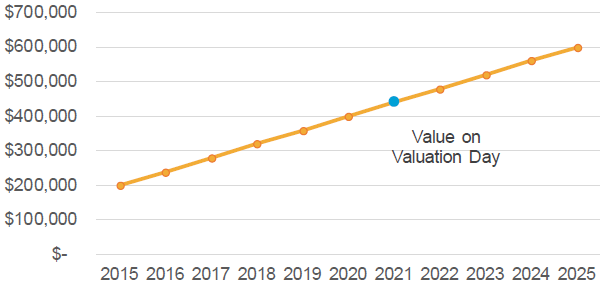

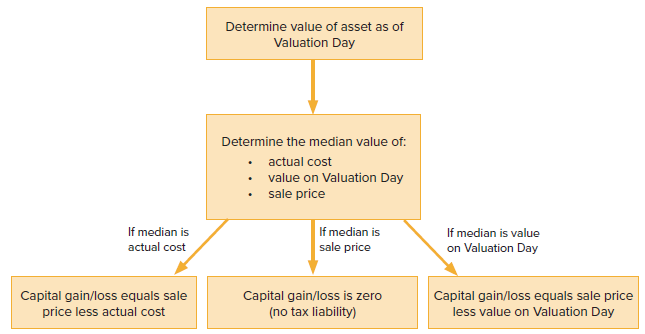

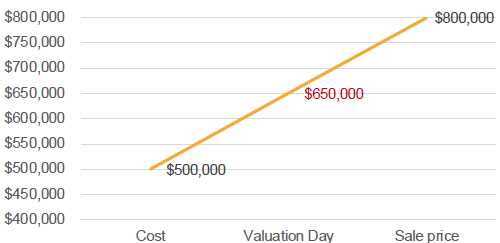

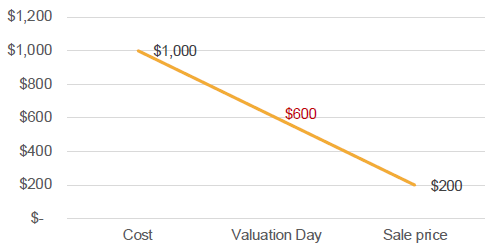

Valuation Day

2. The rules for taxing more capital gains would apply to gains and losses that arise after the implementation date (‘Valuation Day'). This approach would require taxpayers to:

- determine the value of the asset as of Valuation Day (a number of valuation options would be available), and

- calculate the increase or decrease in value from Valuation Day when the asset is sold or disposed of (special rules may apply to limit paper gains and/or losses[7]).

3. The rules for Valuation Day should provide taxpayers a choice between simplicity and accuracy and provide different options for different types of assets. The Group is not proposing that all assets need to be valued by valuers on Valuation Day, as this would impose an unmanageable burden on valuers and unreasonable compliance costs on taxpayers. Instead, taxpayers should have five years from Valuation Day (or to the time of sale if that is earlier) to determine a value for their included assets as at Valuation Day. If no valuation is determined, then a default rule should apply.

Flexible valuation rules

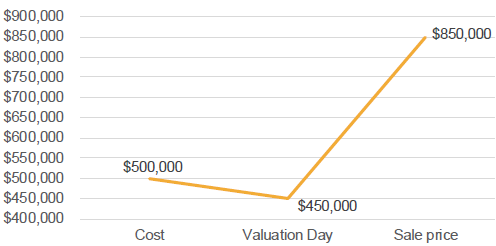

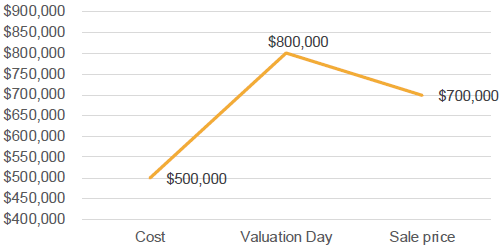

4. The legislation should require that the cost base for included assets will be their value on Valuation Day.[8] This should be supplemented by Inland Revenue guidance on appropriate valuation methods. This approach is consistent with other scenarios where the tax legislation requires a value and allows greater flexibility for taxpayers to pick the most appropriate valuation method for their asset.

5. This guidance should provide taxpayers with safe-harbour valuation methodologies that Inland Revenue will accept and outline what information the taxpayer should file and retain to support their valuation. This guidance should be prepared at the same time as the draft legislation for the new rules to assist with certainty for taxpayers.

6. Inland Revenue should also provide calculators and publish other material to assist taxpayers in determining the value of their included assets. For example, to reduce compliance costs for owners of NZX-listed and ASX-listed shares, Inland Revenue could publish information about the relevant valuations of these shares on Valuation Day.