Preface

Since the release of our Interim Report in September 2018 the Tax Working Group has undertaken further rounds of engagement and consultation. Alongside this process, the Group has developed and further refined its conclusions outlined in the Interim Report.

The engagement process has reached out to various parts of society, including Māori, civil society, tax professionals, business and environmental organisations. There has also been discussion with tax professionals in Australia to learn from their experience. This engagement reflects and is reflected in the work the Group has undertaken since early September.

As might be expected, the submissions on the Interim Report contained a wide variety of opinions. They ranged from full endorsement of the recommendations in the Interim Report, often wishing to see at least some of them go further, through to substantial rejection of the majority of the recommendations.

Those wanting to go further were bunched into two clusters. The first primarily wished the Group to consider matters outside its Terms of Reference, such as the tax:welfare interface and higher tax rates (particularly for those on higher incomes). In this cluster there were also some who wished to revisit areas that the Group had already carefully considered, with a clear majority recommending no change (such as for a financial transactions tax).

The second cluster was largely composed of groups or individuals wishing to strengthen or extend some part of the recommendations. These were most often concerned with environmental issues or the Interim Report's conclusions on behavioural taxes (which some wished to be renamed health promotion taxes).

The Group has carefully considered these submissions but has not accepted them all. In particular, we have adhered to our Terms of Reference, though we have made some incidental comments where we deemed it appropriate.

We have also reaffirmed the views expressed in the Interim Report concerning the purposes of tax. This report does not repeat those sections in full. Similarly, it does not repeat a number of other sections from the Interim Report where we have made no changes.

In other words, the Group's consideration of particular propositions continues to reflect the fundamental proposition that there are three main ways in which the tax system supports the wellbeing of New Zealanders: as a fair and efficient source of revenue; as a means of redistribution; and as a policy instrument to influence behaviours.

There was broad but not universal support for this position from submitters. As far as the Interim Report's specific recommendations are concerned, those rejecting them did so primarily in relation to the chapter and the appendix dealing with the extension of capital gains taxation. Where possible, the Group has taken account of those submissions, especially in relation to the vexed question of compliance costs.

Since the Interim Report the Group's internal discussions have focused primarily on the extension of capital taxation. Given what capital income is taxed already, that has meant consideration of the taxation of capital gains. Despite differences of opinion on how far such taxation should go, the Group agreed that whatever is done should be part of the general income tax system and not a separate capital gains tax regime. The reasons for this are explained in this report.

As I have indicated above, the Group was not of one mind on whether the proposed regime should proceed. A clear majority (eight to three) supported that position. But I should note and thank the three in the minority (Joanne Hodge, Kirk Hope and Robin Oliver) who played a full part in the lengthy development of the technical details. Their contributions were invaluable.

It needs to be emphasised that this difference of judgement relates to the rather simplistic binary decision of being for or against the package of capital gains taxation as a whole. In reality, that is not the only question for the Government (or Parliament) to consider.

As this report emphasises, it is possible to introduce the package in whole or in part, whether all at once or in stages. The balance between revenue and equity on the one hand and complexity and compliance costs on the other differs between asset classes. The most complex asset class is arguably the active business one - as Volume II of this report demonstrates.

This report is about much more than capital gains taxation. I would draw attention, in particular, to the work done on encapsulating the Wellbeing Framework within a Māori world view (Te Ao Māori). This then flows into the substantive section on environmental taxation that goes beyond the near-term challenges to a longer-term tax framework to underpin a circular economy.

It should be noted that no attempt has been made to incorporate possible revenue from environmental taxation in the development of revenue- or fiscally-neutral packages. Suffice to say that environmental tax revenue could be recycled in a number of ways, especially to fund and support a faster transition to a circular economy, as well as offsetting the impact of such taxes on modest-income households.

Finally, let me thank all the members of the Group for their thoughtful participation and especially their forbearance of my occasional impatience. Our officials have been dedicated and assiduous in carrying out their tasks. It is difficult to single out anybody but Bevan Lye's work as the principal scribe on the Interim and Final Reports has been masterful. Last but far from least, our independent advisor, Andrea Black, has laboured mightily to ensure a diversity of views has come before us.

Hon Michael Cullen, KNZM

Chair, Tax Working Group

February 2019

Tax Working Group members:

Marjan van den Belt

Professor Craig Elliffe

Joanne Hodge

Kirk Hope

Nick Malarao

Geof Nightingale

Robin Oliver, MNZM

Hinerangi Raumati, MNZM

Michelle Redington

Bill Rosenberg

Independent Advisor:

Andrea Black

Executive summary

A national conversation on the future of tax

1. Over the past year, the Tax Working Group has engaged in a national conversation with New Zealanders about the future of the tax system. Thousands of New Zealanders - including iwi, businesses, unions and other organisations - have had their say. It is clear to the Group that tax matters to everyone.

2. There is good reason for this passion. The tax system underpins the living standards of New Zealanders in three important respects: as a source of revenue for public services, as a means of redistribution, and as a policy instrument in its own right. The Group has been alert to these multiple purposes in the course of its work.

3. The Group also considers it is important to bring a broad conception of wellbeing and living standards to its work, including a consideration of Te Ao Māori perspectives on the tax system. This approach reflects the composition of the Group, which includes members with a diverse range of skills and experience, including from beyond the tax system.

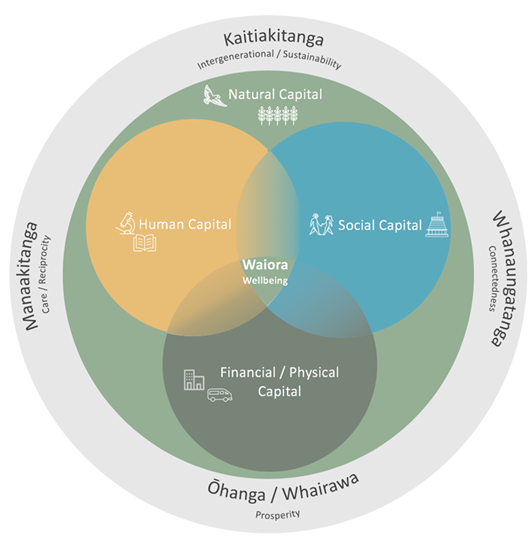

4. As part of this work, the Group has begun to develop a policy framework that would bring together concepts from Te Ao Māori, the four capitals of the Living Standards Framework, and principles of tax policy design.

5. This framework - He Ara Waiora - draws upon the concepts of waiora (wellbeing), manaakitanga (care and respect), kaitiakitanga (stewardship/guardianship), whanaungatanga (relationships and connectedness) and ōhanga (prosperity).

6. The Group's work on He Ara Waiora appears to have resonated with many people. In light of this feedback, discussions have been initiated with the Treasury about how He Ara Waiora could inform the ongoing evolution of the Living Standards Framework.

The structure, fairness and balance of the tax system

7. One of the key tasks for the Group has been to assess the structure, fairness and balance of the tax system. Although the tax system has many strengths, the Group has found that the tax system relies on a relatively narrow range of taxes and is not particularly progressive. There are a number of reasons for these outcomes but two issues it can address within its Terms of Reference stand out for the Group:

- The treatment of capital gains. Unlike most other developed countries, New Zealand does not generally tax income in the form of capital gains (except in some specified instances). The inconsistent treatment of capital gains reduces the fairness of the tax system. It is also regressive, because it benefits the wealthiest members of our society. Both effects weigh against the sense that New Zealanders are all making a fair contribution, and risk undermining the social capital that sustains public acceptance of the tax system and so our shared prosperity in the long term.

- The treatment of natural capital. New Zealand makes relatively little use of environmental taxation. There are clear opportunities to increase environmental taxation, both to broaden the revenue base and to help address the significant environmental challenges we face as a nation.

Final conclusions

The taxation of capital gains

8. All the members of the Group agree that there should be an extension of the taxation of capital gains from residential rental investment properties. Eight members of the Group support the introduction of a broad approach to the taxation of capital gains. This would involve a realisation-based tax that is applied to capital gains on a broad range of assets, at full rates, with no allowance for inflation.

9. In reaching this judgement the majority of the Group accepts that extending the taxation of capital gains would involve an increase in compliance and efficiency costs but judges that these costs would be outweighed by reductions in investment biases, as well as improvements to the fairness, integrity and fiscal sustainability of the tax system. Moreover, some of these costs could be offset by other measures within a package of tax reform.

10. Three members of the Group have reached a different judgement.[1] These members prefer the incremental approach of extending the tax base carefully over time, which they consider has served New Zealand well over many years of tax reform. In their judgement, the revenue benefits, perceptions of fairness and possible integrity benefits, would be outweighed by adverse efficiency impacts, increased compliance and administration costs and fiscal risk.

Choices and options

11. The Government does not face a binary choice regarding whether or not to extend capital gains taxation. There is a spectrum of choices for the coverage of assets and the inclusion of each asset class will come with its own costs and benefits.

12. At one end of the spectrum, there is a clear case to include residential rental investment properties. At the other end of the spectrum, there will be greater complexity regarding the treatment of corporate groups, unlisted shares and business goodwill.

13. For this reason, the Government could choose to extend the taxation of capital gains to some asset classes only. The Government also has options about how to stage the timing of introduction, whether to phase in asset classes, whether to grandparent some or all asset classes and whether to apply the deemed return method.

The importance of effective implementation

14. Regardless of their position on the merits of extending the taxation of capital gains, all members agree that the introduction of a system for taxing capital gains would be a significant endeavour requiring the full attention of the Government.

15. If the Government decides to proceed, it is crucial that Inland Revenue is fully resourced and has the capability to develop and implement the new tax. The policy and legislative processes must also include thorough consultation with a diverse range of voices, using both formal and informal channels.

16. The Group also notes that the Government's stated timeframes for implementing tax reform will be challenging. The Government will need to ensure additional resources are available for implementation if these timeframes are to be achieved.

17. If the Government decides not to extend the taxation of capital gains to all asset classes, Inland Revenue will need to enforce fully the existing capital/revenue boundary. This includes taking test cases, as well as policy and investigative attention to existing areas of concern.

Environmental and ecological outcomes

18. The Group considers there is significant scope for the tax system to play a greater role in sustaining and enhancing New Zealand's natural capital. New Zealand faces significant environmental challenges that require profound change to existing patterns of economic activity. Taxation is one tool - alongside regulation and spending measures - that can support and guide this transition.

19. The task for policymakers is to think in terms of systems change and to develop a set of goals and principles that can guide a transition, over many decades, to a more sustainable economy.

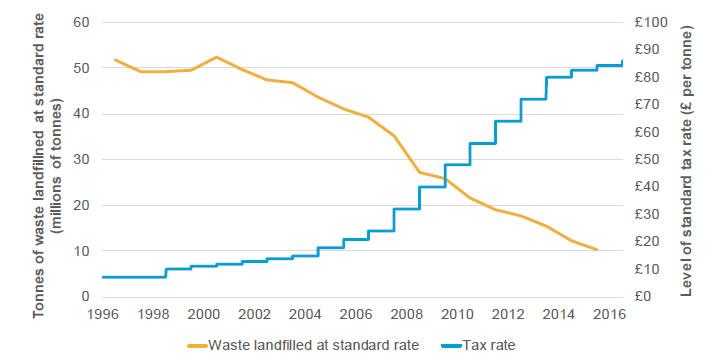

20. In the short term, the Group recommends better use of environmental taxes to price negative environmental externalities. Environmental taxes can be a powerful tool for ensuring people and companies better understand and account for the impact of their actions on the ecosystems on which they depend. The immediate priorities should be to expand the coverage and rate of the Waste Disposal Levy, strengthen the Emissions Trading Scheme and advance the use of congestion charging.

21. In the medium term, environmental tax revenue should be used to help fund a transition to a more sustainable economy.

22. In the longer term, environmental taxes could become a much more significant part of the tax base through the development and adoption of innovative new tools to measure and value environmental impacts.

23. As an initial step, the Group has developed a framework for deciding when to apply taxes to address negative environmental externalities.

A framework for taxing negative environmental externalities[2]

Taxation can be used as a tool to enhance natural capital when unpriced externalities lead to the over-exploitation of resource stocks and degrade the integrity of ecosystems.

The benefits of using taxation as an instrument may be greater when there is high behavioural responsiveness, a diversity of responses available and significant revenue-raising potential.

The suitability of taxation as a policy instrument (relative to other potential instruments) can be assessed through the following criteria: measurability, risk tolerance and scale.

The principles of tax policy design described in Chapter 2 of this report can also apply to environmental taxes. Building off these, there are seven design principles that warrant particular attention: Māori rights and interests must be acknowledged and addressed; distributional impacts must be assessed and mitigated; the suite of responses should reflect the full cost of externalities; the price should vary locally where there is local variation in impacts; international linkages should be considered; the tax should be integrated with other policy; and intertemporal fairness should be considered.

24. The Group has also found that New Zealand has limited institutional capability to design and implement environmental taxes. The Group recommends that the Government strengthen its environmental tax capability. This includes support for the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment, which should be resourced to provide independent advice on environmental tax policy.

The taxation of business and savings

Business and productivity

25. The current approach to the taxation of business is largely sound. The Group does not see a case to reduce the company rate at the present time or to move away from the imputation system. However, the Government should continue to monitor developments in company tax rates around the world, particularly in Australia. The tax rate for Māori authorities also remains appropriate (although the rate should be extended to the subsidiaries of Māori authorities). The Group recommends against introducing a progressive company tax.

26. The Group has investigated and recommended a number of tax measures that could enhance productivity. These include changes to the loss-continuity rules, expanding deductions for ‘black-hole' expenditure and concessions for nationally significant infrastructure projects. Some or all of these measures could form part of a package of tax reform.

27. The Group also assessed the merits of restoring building depreciation deductions. Subject to fiscal constraints, the Government could consider restoring depreciation deductions if capital gains taxation is extended.

28. The main focus of many submissions, however, was on the treatment of multinationals and digital firms. In this regard, the Group notes that New Zealand is currently participating in discussions at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) on the future of the international tax framework. The Group supports this process but recommends that the Government stand ready to implement an equalisation tax on digital services if a critical mass of other countries move in that direction.

Retirement savings

29. New Zealand currently offers few tax incentives for retirement savings. The Group does not see a case to reform radically the taxation of retirement savings. However, the Group does support an increase in the tax benefits for low- and middle-income earners provided through KiwiSaver to encourage people to put more away for their retirement. There is also a case to exempt the New Zealand Superannuation Fund from New Zealand tax obligations.

30. The Group notes that, as lifespans have increased, people are now spending a much greater proportion of their lives in retirement. Although the Group has decided it is not necessary to adjust the tax system for inflation, we have identified a need for further work on options to maintain the purchasing power of people's savings through their retirement.

Personal income taxation

31. Any changes to personal income taxation will need to reflect the objectives of the Government.

- If the Government wishes to improve incomes for very low-income households, the best means of doing so will be through welfare transfers.

- If the Government wishes to improve incomes for certain groups of low- to middle-income earners, such as full-time workers on the minimum wage, then changes to personal income taxation may be a better option.

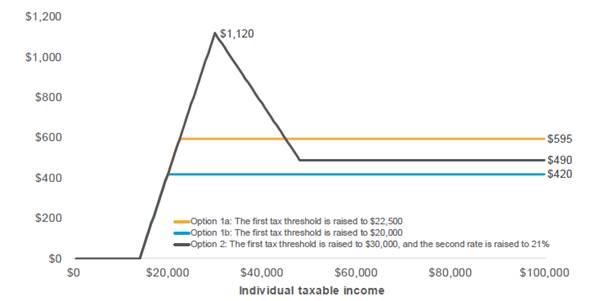

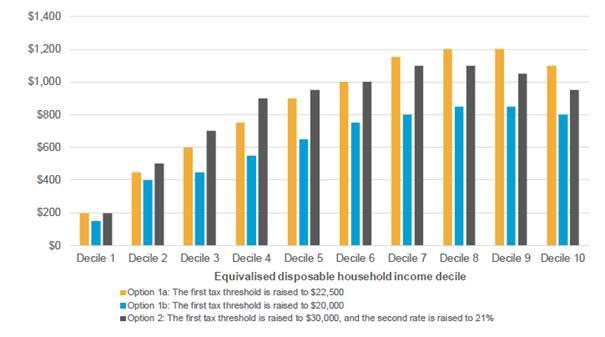

32. The Group has discussed a range of options to increase the progressivity of the personal tax system. The Group's preferred approach is to increase the bottom tax threshold. This could potentially be combined with an increase in the second marginal tax rate.[3]

33. Alongside these tax changes, the Government should consider increasing net benefit payments to ensure beneficiaries receive the same post-tax increase as other people on the same income. This would provide a fairer redistribution of revenue across individuals and have a greater impact on poverty reduction.

34. Overall, the personal tax changes discussed in this report are likely to have a minor impact on income inequality. A material reduction in income inequality through the personal tax system would require broader income tax changes, including an increase in the top marginal rate. Such a change is beyond the scope of the Group's Terms of Reference.

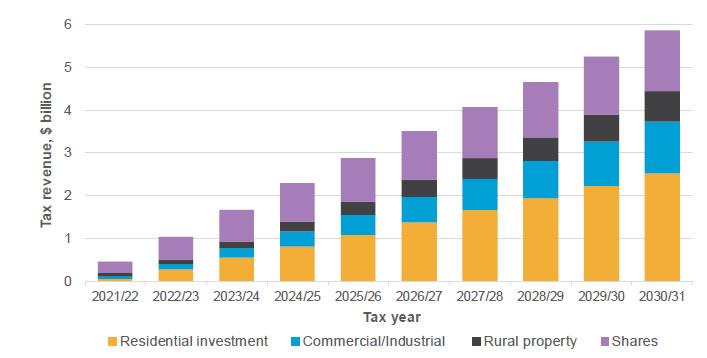

Potential packages for tax reform

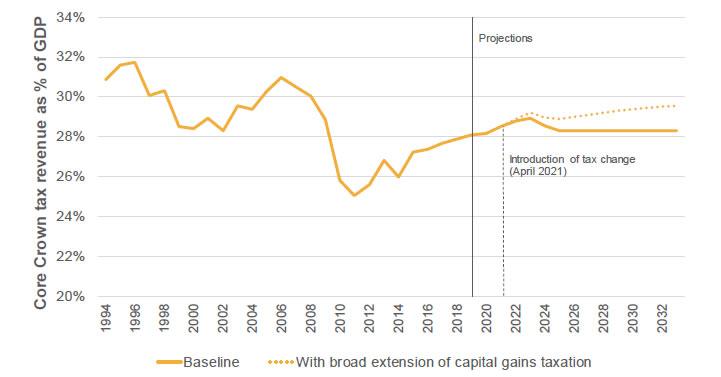

35. A broad extension of the taxation of capital gains (as set out in Volume II) is projected to raise approximately $8.3 billion over five years. The revenue is expected to increase over time, rising to a long-run average of 1.2% of gross domestic product (GDP) per annum, but it will also be volatile. In light of these revenue projections, Ministers have directed the Group to develop revenue-neutral packages of tax reform for the Government's consideration.

36. The Group has developed four illustrative packages:

- A package that increases progressivity through reductions in personal income tax.

- A package with a greater focus on measures to support businesses and housing affordability.

- A package with a greater focus on supporting savers, particularly those on lower incomes.

- A package with a more diversified focus, where business tax measures are deferred to enable greater savings measures.

37. While each package focuses on different themes, they all involve substantial reductions in personal income tax that deliver the greatest proportional benefits to lower income earners. Depending on its objectives, the Government could combine these or other measures into alternative packages for tax reform.

38. The best use of revenue from extending the taxation of capital gains will ultimately depend on the Government's priorities. Tax reform is only one choice. The Government also has a wider set of options to consider beyond the tax system.

39. The Group recommends that the Government assess the options for tax reform against other needs and priorities to determine what would best enhance the wellbeing of New Zealanders.

Other opportunities to improve the tax system

40. The Interim Report contained recommendations on many other aspects of the tax system. Time constraints have precluded further in-depth investigation of these issues but the recommendations remain an essential part of the Group's prescription for reform.

Matters requiring significant attention by the Government

The future of work

41. The Group is concerned that the effectiveness of the pay as you earn (PAYE) withholding system will reduce if labour market changes increase the proportion of self-employed workers in the future. The Group therefore supports Inland Revenue's efforts to increase the compliance of the self-employed.

42. The Group also supports expanding the use of withholding taxes to increase compliance and recommends that withholding be extended as far as practicable (including to platform service providers, such as ride-sharing companies) so long as this does not impose unreasonable compliance costs.

The integrity of the tax system

43. The integrity of the tax system requires constant vigilance. Tax avoidance erodes social capital. It is also fundamentally unfair, because it means that compliant taxpayers must pay more to make up for the lost revenue.

44. At the moment, there appears to be a set of integrity risks associated with the use of closely held companies. Some of the underlying problems derive from the fact that the company and top personal tax rates are not aligned but there is a clear need for Inland Revenue to strengthen enforcement of the rules for closely held companies. Extending the taxation of capital gains could also reduce integrity risks by reducing opportunities for tax planning and tax avoidance.

45. The Group also recommends further developing measures to reduce the extent of undeclared and cash-in-hand transactions (sometimes known as the ‘hidden economy'). These measures could include increasing the reporting of labour income and even the removal of tax deductibility if a taxpayer has not followed labour income withholding or reporting rules.

46. Tax collection could be enhanced by increasing the remedies available to the Commissioner of Inland Revenue to address non-compliance. The Group recommends the use of departure prohibition orders and introducing a regime similar to Australia's Director Penalty Notice for serious cases, where the directors are the economic owners of the business and there has been persistent or intentional non-compliance.

47. The Group also recommends establishing a single Crown debt collection agency, to achieve economies of scale and more equitable outcomes across all Crown debtors.

The administration of the tax system

48. The Group considers there is a need for greater public access to data and information about the tax system. Inland Revenue should review whether the information and data it currently collects offers the most useful insights or whether other datasets would better respond to the needs and interests of the public and future policy development. It is particularly important to have better data about the distribution of wealth in New Zealand.

49. The Group also considers there is a need to improve the resolution of tax disputes. The Group recommends establishing a taxpayer advocacy service to assist taxpayers in disputes with Inland Revenue and also wishes to ensure the Office of the Ombudsman is adequately resourced to carry out its functions in relation to tax.

Tax technical capability

50. Inland Revenue must maintain deep technical expertise, alongside strategic policy capability. The Group strongly recommends that Inland Revenue continue to invest in the technical and investigatory skills of its staff. The Group also expects to see the Treasury playing a stronger role in the development of tax policy than it has in recent years.

Matters requiring further work

Charities

51. The Group received many submissions regarding the treatment of business income for charities and whether the tax exemption for charitable business income confers an unfair advantage on the trading operations of charities.

52. The Group considers that the underlying issue is more about the extent to which charities are distributing or applying the surpluses from their activities for the benefit of their charitable purposes.

53. The core question is whether the broader policy settings for charities encourage appropriate levels of distribution. In light of this, the Group recommends that the Government periodically review the charitable sector's use of what would otherwise be tax revenue, to verify that the intended social outcomes are actually being achieved.

54. Another area of concern relates to the treatment of private charitable foundations and trusts. The rules about these entities appear to be unusually loose. The Government should consider whether to apply a distinction between privately controlled foundations and other charitable organisations, with a view to removing concessions for privately controlled foundations or trusts that do not have arm's length governance or distribution policies.

55. The Group notes that the Government has launched a review of the Charities Act 2005. The Group has provided its analysis to Inland Revenue and the Department of Internal Affairs for further consideration as part of the Charities Review and the Tax Policy Work Programme.

Goods and services tax (GST)

56. GST is an important source of revenue for the Government. Yet the Group has received many submissions calling for a reduction in the GST rate - or for the introduction of new GST exceptions - to reduce the impact of GST on lower-income households.

57. The Group acknowledges public concern about the regressive nature of GST but has decided not to recommend a reduction in the GST rate or the introduction of new GST exceptions. This is because other measures, such as increases in transfers or changes to the personal tax system, will increase progressivity more effectively than reductions to GST.

58. One problematic aspect of GST relates to the treatment of financial services, which are not subject to GST for reasons of administrative complexity. The Group has considered a number of options for taxing the consumption of financial services but has not been able to identify a means of doing so that is both feasible and efficient. However, the Government should monitor international developments in this area.

59. The Group does not recommend introducing a financial transactions tax at this point.

Corrective taxes

60. A corrective tax is a tax that is intended to influence behaviour and lead to better health and wellbeing outcomes for New Zealanders. Outside of the environmental sphere, New Zealand currently levies corrective taxes on alcohol and tobacco.

61. Some submitters have suggested the development of a framework for deciding when to apply corrective taxes (similar to the framework developed by the Group for the use of environmental taxes). The Group supports this suggestion.

62. Detailed recommendations on the rates of alcohol and tobacco excise are beyond the expertise of the Group. However, the Group does recommend that the Government simplify the schedule of alcohol excise rates and is concerned about the distributional impact of further increases in tobacco excise beyond the increases that have already been scheduled.

63. The Group acknowledges widespread public interest in adopting a sugar tax. The case for a sugar tax must rest on a clear view of the Government's objectives. If the Government wishes to reduce the consumption of sugar across the board, a sugar tax is likely to be an effective response. If the Government wishes to reduce the sugar content of particular products, regulation is likely to be more effective. In either case, there is a need to consider the use of taxation, alongside other potential policy responses.

Final words

64. Everyone has an opinion on tax. It is a subject that arouses strong passions and even deep disagreements - but it is also a way in which we come together as a society (‘nāu te rourou, nāku te rourou') to contribute to our nation's broader prosperity (‘ka ora ai te iwi'). Tax should matter to everyone.

65. Over the past year, thousands of New Zealanders have shared their thoughts on the future of the tax system. The Group deeply appreciates the generosity of all submitters who took the time to set out their views to us. The submissions have informed and also challenged us. Our recommendations are better for having received them.

66. The process of tax reform will now move into a different phase, as the Government picks up and considers our recommendations. In this new phase, it is vital that public input continues to influence the direction of tax reform.

67. To this end, the Group encourages all New Zealanders to stay involved as the programme of tax reform is developed. Together, we can - and should - shape the future of tax.

Notes

- [1] These members are Joanne Hodge, Kirk Hope and Robin Oliver. A note summarising their view is available at https://taxworkinggroup.govt.nz/resources/twg-bg-4050912-extending-the-taxation-of-capital-gains-minority-view

- [2] See Chapter 4 Environmental and ecological outcomes for a more complete description of the framework.

- [3] The Group's Terms of Reference rule out increases to any rate of personal income tax. However, it would be possible to increase the second marginal tax rate (paired with increases in the bottom tax threshold) such that average tax rates do not increase for higher income earners.

Summary of recommendations

This chapter summarises the Group's final recommendations.

Capital and wealth

1. The majority of the Group recommends a broad extension of the taxation of capital gains.[4]

2. If a broad extension of capital gains taxation were to occur, the Group recommends that it have the characteristics detailed in Volume II of this report. These characteristics are summarised below.

What to tax

The Group:

- recommends including gains and most losses from all types of land and improvements (except the family home), shares, intangible property and business assets.

- recommends not including personal-use assets (such as cars, boats or other household durables).

- considers that some types of transactions relating to collectively owned Māori assets merit specific treatment in light of their distinct context.

- recommends that the Government engages further with Māori to determine the most appropriate treatment of transactions relating to collectively owned Māori assets.

- recommends that the existing rules continue to apply to foreign shares that are currently taxed under the fair dividend rate method of taxation, as well as anything taxed under the financial arrangement rules.

- recommends only taxing gains and losses that arise after the implementation date (Valuation Day).

When to tax

The Group:

- recommends the tax be imposed on a realisation basis in most cases.

- recommends rollover treatment for certain life events (such as death and relationship separations), business reorganisations and small business reinvestment.

How to tax

The Group:

- recommends that capital gains be taxed within the current income tax system and taxed at a person's marginal rates.

- recommends no discount for capital gains and no adjustment for inflation.

- recommends that capital losses be ring-fenced for: portfolio investments in listed shares (other than when they are trading stock); associated party transactions; and losses from Valuation Day assets.

- recommends that capital losses on privately used land be denied entirely.

- recommends that capital losses (other than those described in recommendations (k) and (l) above) be treated in the same way as other tax losses and taxpayers should generally be able to offset losses arising from the disposal of capital assets against ordinary taxable income.

Transitional rules

The Group:

- recommends that taxpayers have five years from Valuation Day (or to the time of sale if that is earlier) to determine a value for their included assets as at Valuation Day.

- recommends that if no valuation is determined, then a default rule apply. (See Volume II for default valuation methods.)

- encourages the Government and Inland Revenue to develop tools and guidance to further assist taxpayers through the Valuation Day process.

Development and implementation

The Group:

- recommends that Inland Revenue be fully resourced and has the capability to develop and implement the new tax.

- encourages Inland Revenue to develop low-cost options for valuations required outside of Valuation Day that are sufficiently robust to maintain the integrity of the system.

- recommends that the policy and legislative processes include thorough consultation with a diverse range of voices, using both formal and informal channels.

- recommends that the policy and legislative process includes coverage of the following issues:

- Identifying further options for reducing the compliance costs.

- Ensuring that the final rules do not create a bias in favour of investment in foreign shares.

- Assessing whether there is a need for information reporting or withholding requirements for capital gains - and, if so, how widely to impose them.

3. The Group does not recommend introducing a wealth tax.

4. The Group does not recommend introducing a land tax.

Environmental and ecological outcomes

5. The Group recommends the Government adopts the framework in Chapter 4 of this report for taxing negative environmental externalities.

Greenhouse gases

The Group:

6. supports a reformed Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) remaining the centrepiece of New Zealand's emissions reduction efforts but recommends it be made more ‘tax-like' - specifically, by providing greater guidance on price and auctioning emissions units to raise revenue (as recommended by the Productivity Commission).

7. recommends periodic review of the ETS to ensure it is fit for purpose and is the best mechanism for pricing greenhouse gas emissions.

8. recommends that all emissions face a price, including from agriculture, either through the ETS or a complementary system.

Water abstraction and water pollution

The Group:

9. recommends greater use of tax instruments to address water pollution and water abstraction challenges if Māori rights and interests can be addressed.

10. recommends further development of tools and capabilities to estimate diffuse water pollution to enable more accurate and effective water pollution tax instruments.

11. recommends introducing input-based tax instruments, including on fertiliser, if significant progress is not made in the near term on implementing output-based pricing measures or other regulatory measures.

Solid waste

The Group:

12. supports the Ministry for the Environment's review of the rate and coverage of the Waste Disposal Levy.

13. supports expanding the coverage of the Waste Disposal Levy.

14. recommends a reassessment of the negative externalities associated with landfill disposal in New Zealand to ascertain if a higher levy rate is appropriate.

15. recommends a review of hypothecation arrangements of the Waste Disposal Levy to ensure funds are being used in the most effective way to move towards a more circular economy.

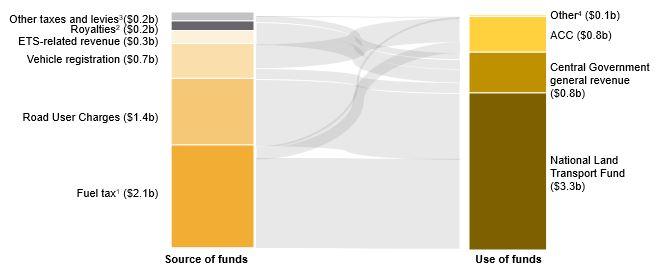

Transport

16. The Group supports current reviews by the Government and Auckland Council into introducing congestion pricing.

Concessions

The Group:

17. recommends costs associated with the care of land subject to a QEII covenant or Ngā Whenua Rāhui be tax deductible.

18. recommends that the Government consider allowing employers to subsidise public transport use by employees without incurring fringe benefit tax.

19. recommends that the Government review various tax provisions specific to farming, forestry and petroleum mining with a view to removing concessions harmful to natural capital, while also considering new concessions that could enhance natural capital.

Other matters relating to environmental taxation

The Group:

20. recommends some or all of environmental tax revenue should be used to help fund a transition to a more sustainable, circular economy.

21. recommends consideration over the longer term of new tools, like an environmental footprint tax, or a natural capital enhancement tax.

22. recommends the Government strengthen its environment tax capabilities, including with the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment.

23. recommends that the Government commission incidence studies to better understand who will incur the costs of new environmental taxes and to design appropriate mitigation measures.

24. recommends further work to rigorously assess how taxes can complement other environmental policy measures and to work through the design principles identified in the Group's framework for taxing negative environmental externalities.

The taxation of business

The Group recommends that the Government:

25. retain the imputation system.

26. not reduce the company tax rate at the present time. However, the Government should continue to monitor developments in company tax rates around the world, particularly in Australia.

27. not introduce a progressive company tax.

28. not introduce an alternative basis of taxation for smaller businesses, such as cashflow or turnover taxes.

29. retain the 17.5% rate for Māori authorities.

30. extend the 17.5% rate to the subsidiaries of Māori authorities.

31. consider technical refinements to the Māori authority rules, as suggested by submitters, in the Tax Policy Work Programme.

32. change the loss-continuity rules to support the growth of innovative start-up firms.

33. reform the treatment of black-hole expenditure, with:

- a new rule to recognise deductions for expenditure incurred by businesses that is not otherwise dealt with under the Income Tax Act 2007, including in respect of abandoned assets and projects.

- a clawback of tax deductions where an abandoned asset or project is subsequently restored, such that those deductions would be capitalised.

- the spreading of black-hole expenditure over five years.

- a safe-harbour threshold of $10,000 to allow upfront deductions for low levels of feasibility expenditure.

34. subject to fiscal constraints, consider restoring depreciation deductions for buildings if there is an extension of the taxation of capital gains. To manage the fiscal costs, the Government could reinstate building depreciation on a partial basis for:

- seismic strengthening only

- multi-unit residential buildings

- industrial, commercial and multi-unit residential buildings.

35. consider tax measures that encourage building to higher environmental standards.

36. consider developing a regime that encourages investment into nationally-significant infrastructure projects.

37. examine the following options to reduce compliance costs:

For immediate action:

- Increase the threshold for provisional tax from $2,500 to $5,000 of residual income tax.

- Increase the closing stock adjustment from $10,000 to $20,000-$30,000.

- Increase the $10,000 automatic deduction for legal fees and potentially expand the automatic deduction to other types of professional fees.

- Reduce the number of depreciation rates and simplify the process for using default rates.

Subject to fiscal constraints:

- Simplify the fringe benefit tax and simplify (or even remove) the entertainment adjustment.

- Remove resident withholding tax on close company-related party interest and dividend payments, subject to integrity concerns.

- Remove the requirement for taxpayers to seek the approval of the Commissioner of Inland Revenue to issue GST Buyer Created Tax Invoices.

- Allow special rate certificates and certificates of exemption to be granted retrospectively.

- Increase the period of validity for a certificate of exemption or special rate certificate.

- Remove the requirement to file a change of imputation ratio notice with Inland Revenue.

- Extend the threshold of ‘cash basis person' in the financial arrangement rules, which would better allow for the current levels of personal debt.

- Increase the threshold for not requiring a GST change-of-use adjustment.

The Government should also review and explore the following opportunities:

- Adjust the thresholds for unexpired expenditure and for the write off of low-value assets.

- Help small businesses reduce compliance costs through the use of cloud-based accounting software.

- Consider compensation for withholding agents if additional withholding tax obligations are imposed.

- Review the taxation of non-resident employees.

- Review whether the rules for hybrid mismatches should apply to small businesses or simple business transactions.

38. The Group recommends that the Government give favourable consideration to exempting the New Zealand Superannuation Fund from New Zealand tax obligations.

International income taxation

The Group:

39. supports New Zealand's continued participation in discussions at the OECD on the future of the international income tax framework.

40. recommends that the Government stand ready to implement a digital services tax if a critical mass of other countries move in that direction and it is reasonably certain New Zealand's export industries will not be materially impacted by any retaliatory measures.

41. recommends that the Government actively monitor developments and collaborate with other countries with respect to equalisation taxes.

42. recommends that the Government ensure, to the extent possible, that New Zealand's double tax agreements and trade agreements do not restrict New Zealand's taxation options in these matters.

Retirement savings

The Group:

43. recommends that the Government, depending on its priorities, consider encouraging the savings of low-income earners by carrying out one or more of the following:

- Refunding the employer's superannuation contribution tax (ESCT) for KiwiSaver members earning up to $48,000 per annum. This refund would be clawed back for KiwiSaver members earning more than $48,000 per annum, such that members earning over $70,000 would receive no benefit.

- Ensuring that a KiwiSaver member on parental leave would receive the maximum member tax credit regardless of their level of contributions.

- Increasing the member tax credit from $0.50 per $1 of contribution to $0.75 per $1 of contribution. The contribution cap should remain unchanged.

- Reducing the lower portfolio investment entity (PIE) rates for KiwiSaver funds (10.5% and 17.5%) by five percentage points each.

44. recommends that the Government consider ways to simplify the determination of the PIE rates (which would apply to KiwiSaver).

Personal income tax

45. The Group's recommendations on personal income tax are dependent on the objectives of the Government.

- If the Government wishes to improve incomes for very low-income households, the Group considers the best means of doing so will be through welfare transfers.

- If the Government wishes to improve incomes for certain groups of low- to middle-income earners, such as full-time workers on the minimum wage, the Group considers changes to personal income taxation may be a better option.

The Group:

46. recommends that the Government consider increases in the bottom threshold of personal tax to increase the progressivity of the personal tax system.

47. recommends that the Government consider combining increases in the bottom threshold with an increase in the second marginal tax rate.

48. suggests that if this higher tax rate is adopted, the Government consider a reduction of the abatement rate of Working for Families tax credits to offset the impact of the increase.

49. prefers increasing the bottom threshold to introducing a tax-free threshold.

50. recommends that the Government consider an increase in net benefit payments to ensure beneficiaries receive the same post-tax increase as other people on the same income.

51. recommends that the Government consider changes to tax rates and thresholds alongside any recommendations made by the Welfare Expert Advisory Group.

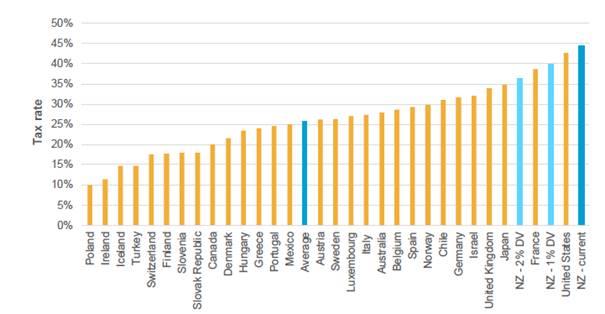

52. recommends that the Government not reduce the top marginal tax rate on vertical equity grounds because it is already low by international standards and it would not increase progressivity of the tax system.

53. notes that many submissions called for increasing top personal tax rates in order to enable policies that would make a material reduction in income inequality through the personal tax system. As such increases are precluded by the Group's Terms of Reference the Group did not undertake an analysis of the options (and their effectiveness).

Future of work

The Group recommends that the Government:

54. support Inland Revenue's efforts to increase the compliance of the self-employed, particularly expanding the use of withholding tax as far as practicable, including to platform providers, such as ride-sharing companies.

55. support the facilitation of technology platforms to assist the self-employed meet their tax obligations through the use of ‘smart accounts' or other technology-based solutions.

56. continue (through Inland Revenue's current work) to use data analytics and matching information for specific taxpayers to identify under-reporting of income.

57. review the current GST requirements for contractors who are akin to employees.

58. align the definitions of employee and dependent contractors for tax and employment purposes.

59. provide more support for childcare costs, though the Group considers this support is best provided outside of the tax system.

Integrity of the tax system

The Group recommends:

60. a review of loss trading, potentially in tandem with a review of the loss-continuity rules for companies.

61. that, for closely held companies, Inland Revenue have the ability to require a shareholder to provide security to Inland Revenue if:

- the company owes a debt to Inland Revenue.

- the company is owed a debt by the shareholder.

- there is doubt as to the ability/and or the intention of the shareholder to repay the debt.

62. further action in relation to the hidden economy, including:

- an increase in the reporting of labour income (subject to not unreasonably increasing compliance costs on business).

- a review of the measures recently adopted by Australia in relation to the hidden economy, with a view to applying them in New Zealand.

- the removal of tax deductibility if a taxpayer has not followed labour income withholding or reporting rules.

63. that Inland Revenue continue to invest in the technical and investigatory skills of its staff.

64. further measures to improve collection and encourage compliance, including:

- making directors who have an economic ownership in the company personally liable for arrears on GST and PAYE obligations where there has been deliberate or persistent non-compliance (as long as there is an appropriate warning system).

- departure prohibition orders.

- aligning of the standard of proof for PAYE and GST offences.

65. the establishment of a single centralised Crown debt collection agency to achieve economies of scale and more equitable outcomes across all Crown debtors.

66. that Inland Revenue strengthen enforcement of rules for closely held companies.

67. that the Government explore options to enable the flexibility of a wider gap between the company and top personal tax rates without a reduction in the integrity of the tax system.

Administration of the tax system

The Group:

68. recommends that the Government:

- fund oversampling of the wealthy in existing wealth surveys.

- include a question on wealth in the census.

- request Inland Revenue to regularly repeat its analysis of the tax paid by high wealth individuals.

- commission research on using a variety of data sources on capital income, including administrative data, to estimate the wealth of individuals.

69. strongly encourages the Government to release more statistical and aggregated information about the tax system (so long as it does not reveal data about specific individuals or corporates that is not otherwise publicly available).The Government could consider further measures to increase transparency as public attitudes change over time.

70. encourages Inland Revenue to publish or make available a broader range of statistics, in consultation with potential users, either directly or (preferably) through Stats NZ.

71. encourages Inland Revenue to collect information on income and expenditure associated with environmental outcomes that are part of the tax calculation.

72. recommends that any further expansion of the resources available to the Ombudsman include consideration of provision for additional tax expertise and possibly support to manage any increase in the volume of complaints relating to the new Crown debt collection agency proposed by the Group.

73. recommends establishing a taxpayer advocacy service to assist with the resolution of tax disputes.

74. recommends that the Government consider a truncated tax disputes process for small taxpayers.

75. recommends the use of the following principles in public engagement on tax policy:

- Good faith engagement by all participants.

- Engagement with a wider range of stakeholders, particularly including greater engagement with Māori (guided by the Government's emerging engagement model for Crown/Māori Relations).

- Earlier and more frequent engagement.

- The use of a greater variety of engagement methods.

- Greater transparency and accountability on the part of the Government.

76. notes the need for the Treasury to play a strong role in tax policy development, and the importance of Inland Revenue maintaining deep technical expertise and strategic policy capability.

77. encourages the continuing use of purpose clauses where appropriate and recommends including an overriding purpose clause in the Tax Administration Act 1994 to specify Parliament's purpose in levying taxation.

Charities

The Group:

78. recommends that the Government periodically review the charitable sector's use of what would otherwise be tax revenue, to verify that intended social outcomes are being achieved.

79. supports the Government's inclusion of a review of the tax treatment of the charitable sector on its Tax Policy Work Programme, as announced in May 2018.

80. notes that the income tax exemption for charitable entities' trading operations was perceived by some submitters to provide an unfair advantage over commercial entities' trading operations.

81. notes, however, that the underlying issue is the extent to which charitable entities are accumulating surpluses rather than distributing or applying those surpluses for the benefit of their charitable activities.

82. recommends that the Government consider whether to apply a distinction between privately controlled foundations and other charitable organisations.

83. recommends that the Government consider whether to amend the deregistration tax rules to more effectively keep assets in the sector or to ensure there is no deferral benefit through the application of these rules.

84. recommends that the Government review whether it is appropriate to treat some not-for-profit organisations as if they were final consumers or, alternatively, to limit GST concessions to a smaller group of non-profit bodies, such as registered charities.

85. recommends that the Government consider whether the issues identified by the Group in relation to charities have been fully addressed or whether further action is required, following the conclusion of the review of the Charities Act 2005.

GST and financial transaction taxes

The Group:

86. recognises the significant public concern regarding GST but does not recommend a reduction in the rate of GST. This is because lowering the GST rate would not be as effective at targeting low- and middle-income families as either:

- welfare transfers (for low-income households), or

- personal income tax changes (for low- and middle-income earners).

87. does not recommend removing GST from certain products, such as food and drink, on the basis that the GST exceptions are complex, poorly targeted for achieving distributional goals and generate large compliance costs. Furthermore, it is not clear whether the benefits of specific GST exceptions are passed on to consumers.

88. considers there is a strong in-principle case to apply GST to financial services but there are significant impediments to a workable system. The Government should monitor international developments in this area.

89. does not recommend applying GST to explicit fees charged for financial services.

90. recognises that there is active international debate on financial transaction taxes, which should be monitored but does not recommend the introduction of a financial transactions tax at this point.

91. has already reported to Ministers on the issue of GST on low-value imported goods and the Government recently introduced a Bill in December 2018 advancing proposals to address the issue. [5]

Corrective taxes

The Group:

92. supports the development of a framework for deciding when to apply corrective taxes (similar to the framework developed by the Group for the use of environmental taxes).

93. recommends that the Government review the rate structure of alcohol excise with the intention of rationalising and simplifying it.

94. recommends that the Government prioritise other measures to help people stop smoking before considering further large increases in the tobacco excise rate beyond the increases currently scheduled.

95. recommends that the Government develop a clearer articulation of its goals regarding sugar consumption and gambling activity.

Housing

The Group:

96. recommends that the Productivity Commission inquiry into local government financing considers a tax on vacant residential land.

97. considers that residential vacant land taxes would be best levied as local taxes rather than a national tax.

98. recommends that the ‘ten-year rule' which taxes a gain from the sale of property where the property has increased in value due to changes in land use regulation be repealed.

99. recommends that disclosure of the purchaser's IRD number on the Land Transfer Tax Statement should be required when purchasing a main home.

1 The purposes of tax

1. Over the past year, the Tax Working Group has engaged in a national conversation with New Zealanders about the future of the tax system. Thousands of New Zealanders - including iwi, businesses, unions and other organisations - have shared their thoughts and had their say on the future of tax.

2. The views and suggestions have differed from submission to submission. Yet the Group has been struck by the depth of interest and passion expressed by all submitters on the issues before us. It is clear that tax matters to everyone.

3. There is good reason for the passion we have seen. If the ultimate purpose of public policy is to improve wellbeing, then few areas of public policy contribute as much to the wellbeing of New Zealanders as the tax system.

4. There are three main ways in which the tax system supports the wellbeing of New Zealanders:

- A fair and efficient source of revenue. Taxes provide revenue for the Government to fund the public goods and services that underpin our living standards. The tax system thus represents a way in which citizens come together to channel resources for the collective good of society.

- A means of redistribution. Taxes fund the redistribution that allows all New Zealanders, regardless of their market income, to participate fully in society. While much of this redistribution occurs through the transfer system, the progressive nature of income tax means that the tax system also plays a role in reducing inequality.

- A policy instrument to influence behaviours. Taxes can also be used as an instrument to achieve specific policy goals by influencing behaviour. Taxes influence behaviour by changing the price of goods, services or activities; taxes can discourage certain activities and favour others. In this way, taxes can complement - or even replace - traditional policy tools, such as regulation and spending. This may be particularly important in the health and environmental spheres.

5. In light of these perspectives, the Group has decided to take a rounded view on the purpose of the tax system. The tax system is essential as a source of revenue to the Government - but it is also an important tool that can be used positively to pursue distributional goals, shape behaviour, improve living standards and develop sustainably. The Group has been alert to these multiple purposes in developing its recommendations.

2 Frameworks for assessing tax policy

1. The Group considers it is important to bring a broad conception of wellbeing and living standards to its work on the tax system. This approach reflects the composition of the Group, which includes members with a diverse range of skills and experience, including perspectives from beyond the tax system.

2. Many factors affect living standards and many of these factors have value beyond their contribution to material comfort. Only a subset of those values can be captured in monetary terms but non-monetary factors are key determinants of wellbeing and living standards. As an example, certain types of economic activity may increase material comfort but reduce wellbeing overall, if the by-products of that activity degrade the natural environment.

3. To measure wellbeing comprehensively, income measures must therefore be supplemented with measures of other factors, such as health, connectedness, security, rights and capabilities, and environmental and ecological sustainability. In the Interim Report the Group applied three perspectives for assessing the full range of impacts from tax policy: the Treasury's Living Standards Framework, Te Ao Māori perspectives, and the established principles of tax policy design.

4. These frameworks complement each other. A combination of these frameworks also led the Group to develop a specific framework for deciding when to use taxation to achieve environmental and ecological outcomes. (This framework is discussed in Chapter 4.)

The Living Standards Framework

5. The Living Standards Framework identifies four capital stocks that are crucial to wellbeing: financial and physical capital, human capital, social capital and natural capital. Wellbeing depends on the sustainable development and distribution of the four capitals, which together represent the comprehensive wealth of New Zealand.

6. The Living Standards Framework encourages policymakers to explore how policy change affects the four capitals. It widens the scope of analysis to include a more comprehensive range of factors, distributional perspectives and dynamic considerations. In this way, the Living Standards Framework is consistent in intent with international wellbeing frameworks, such as the United Nation's Sustainable Development Goals (Ormsby 2018).

Te Ao Māori perspectives on wellbeing and living standards

7. The Group has also been working with Māori academics and experts to develop a framework that draws on principles from Te Ao Māori, the Living Standards Framework and the principles of tax policy design, to arrive at a more holistic view of wellbeing.

8. As discussed in the Interim Report, this prototype framework is centred on the concept of waiora. Waiora is commonly used in Te Ao Māori to express wellbeing; it comes from the word for water (wai) as the source of all life. Accordingly, the framework is called He Ara Waiora - A Pathway towards Wellbeing.

9. He Ara Waiora draws on four tikanga principles: manaakitanga (care and respect); kaitiakitanga (stewardship/guardianship); whanaungatanga (the relationships/connections between us); and ōhanga/whairama (prosperity). These principles support the preservation and sustainable development of the four capitals of the Living Standards Framework.

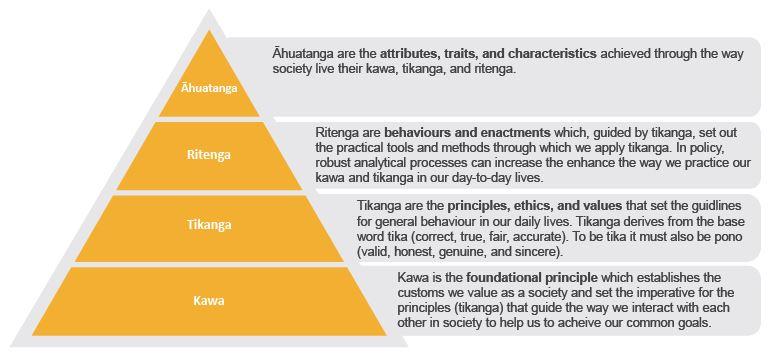

10. During the Group's engagement with Māori academics and experts, Associate Professor Mānuka Henare proposed that these tikanga sit within an integrated framework that incorporates a clear sense of purpose, as well as guidance for how policy is developed and implemented, and performance and accountability measures. Figure 2.2 illustrates what such an integrated framework might look like.

11. In this framework, the concept of waiora or wellbeing would be encapsulated in kawa. This moral imperative in supporting wellbeing could be grounded in the ‘Āta noho' principle from the preamble of the Māori text of Te Tiriti o Waitangi (the Treaty of Waitangi) - meaning that the moral imperative for the tax system could be that all New Zealanders live a life they value, with specific recognition of Māori living the lives that Māori value and have reason to value.[6] The four tikanga identified in figure 2.1 map across to the principles, ethics and values in figure 2.2, while the ritenga and āhuatanga in figure 2.2 are areas that require further development to enable practical application and understanding of impact.

12. The importance of addressing each level of this framework was reinforced in discussions in a series of hui in October. The Group heard broad support for the intent of the work as a meaningful reflection of Te Tiriti o Waitangi, reflecting our continuing maturation as a nation. While the provenance of tikanga resides with Māori, values that are derived from tikanga have a strong resonance with contemporary New Zealand. However, participants suggested that further work is needed to preserve the integrity of the use of tikanga when applied to policy. There should also be awareness and careful navigation of the range of understandings of tikanga in different contexts and places in the country.

13. There was also a view that a tikanga framework should have a broad ambit, rather than just focus on tax - because its value will come from the extent to which it improves the lives of Māori and all New Zealanders.

14. In light of this feedback, discussions have begun with the Treasury about how He Ara Waiora might inform the evolution of the Living Standards Framework. A discussion paper on the future development of He Ara Waiora will be released to keep the public informed on this progress.

15. The process around He Ara Waiora is only just beginning. The Group looks forward to seeing how this work influences policy over time.

Figure 2.1: He Ara Waiora - A Pathway towards Wellbeing

Figure 2.2: A proposed integrated framework

Source: The Treasury (2018)

The established principles of tax policy design

16. Previous tax reviews, in New Zealand and elsewhere, have used a relatively consistent set of principles to assess the design of the tax system. These principles are:

- Efficiency - minimising impediments to economic growth and avoiding distortions to the use of resources.

- Equity and fairness - achieving fairness, including through enhancements to ‘horizontal equity' (the principle that people with similar income and assets should pay the same amount in taxes) and ‘vertical equity' (the principle that those with higher income or assets should pay higher amounts of tax). Procedural fairness is also important for a tax system.

- Revenue integrity - minimising opportunities for tax avoidance and arbitrage.

- Fiscal adequacy - raising sufficient revenue for the Government's requirements.

- Compliance and administration costs - minimising the costs of compliance and administration and giving taxpayers as much certainty as possible.

- Coherence - ensuring that individual tax rules make sense in the context of the entire tax system.

17. Two further important principles in the tax system are predictability and certainty - meaning that taxpayers should be able to understand clearly what their obligations are before those obligations are due.

18. The Group considers these principles remain valid and useful in assessments of the tax system, particularly when considering the costs and benefits of options for reform. These principles complement the system's perspective offered by a broader living standards analysis. In turn, the other frameworks discussed in this chapter will help policymakers interpret and apply these principles in the future.

Notes

- [6] The preamble of the Māori text of Te Tiriti states, “kia tohungia ki a ratou o ratou rangatiratanga me to ratou wenua, kia mau tonu hoki te Rongo ki a ratou me te Atanoho hoki”. This is translated in principle as the desire “to preserve to them their full authority as leaders (rangatiratanga) and their country (to ratou wenua) and that lasting peace (Te Rongo) may always be kept with them and continued life as Māori people (Atanoho hoki)”, (Henare, 1988).

3 The structure, fairness and balance of the tax system

1. Over the past year, the Group has carefully examined the tax system to form a view about its overall structure, fairness and balance.

2. These are subjective concepts and there are different ways to work towards a judgement on them. The Group has borne the following questions in mind in the course of its work:

- Does the tax system treat income consistently, no matter how it is earned and in which sectors it is earned?

- Does the tax system minimise opportunities for tax avoidance?

- Are the bases of the tax system likely to be sustainable over time?

- Should taxation be used as a tool to influence behaviour?

3. The Submissions Background Paper began the process by setting out the main features of the tax system, while the Interim Report provided the Group's initial views on these features. This chapter presents the Group's final assessment on the structure, fairness and balance of the tax system.

Key features of the tax system

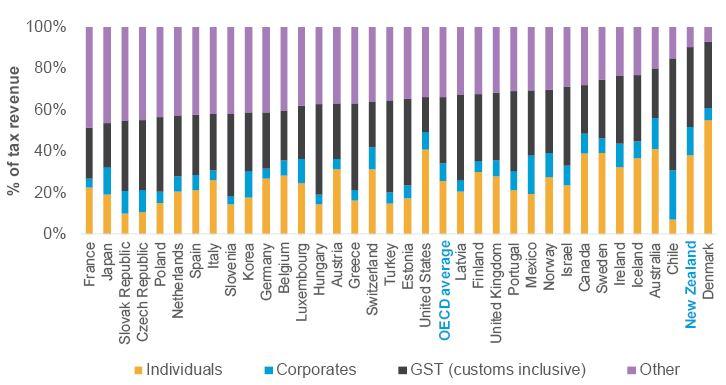

4. In the Interim Report, the Group highlighted two distinctive features of the tax system - its reliance on a relatively narrow range of taxes and its relative lack of progressivity (compared to other developed countries).

The range of taxation

5. New Zealand's current tax system is underpinned by a tax policy framework known as ‘broad base, low rate'. In a broad-based system, there should be few exceptions to the base on which the tax is levied. The benefit of a broad-based system is that it allows the Government to raise substantial amounts of revenue at relatively low rates of taxation.

6. The tax system relies on income tax (mainly personal and company) and goods and services tax (GST). The broad base, low rate framework applies to each of these taxes. New Zealand raises about 90% of its tax revenue from these two taxes. Corrective taxes, such as tobacco and alcohol excise, are the third largest source of revenue.

7. Compared to other developed countries, however, New Zealand makes little use of other sources of taxation, such as environmental taxes and social security levies. Thus, while the taxes levied by New Zealand have broad bases, the overall range of taxation is relatively narrow.

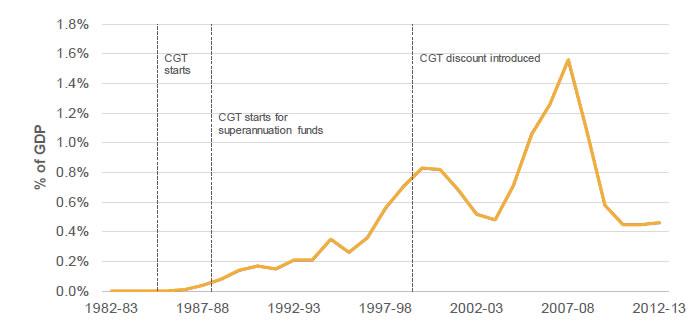

8. New Zealand's treatment of capital gains is also distinctive. Unlike other developed countries, New Zealand does not generally tax capital gains.

9. The most significant gains currently outside the tax net are gains from the sale of land and housing (other than by developers, dealers or speculators), shares (other than portfolio investments in non-resident companies), business goodwill and intellectual property, in cases where those assets have been acquired for a purpose other than sale.

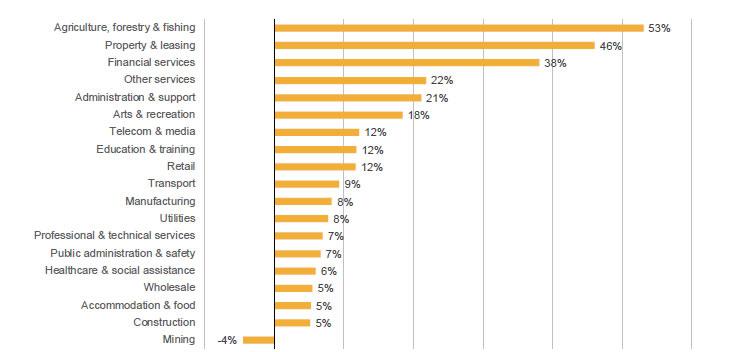

Figure 3.1: Source of tax revenue across OECD countries (2015)

Source: OECD

New Zealand’s approach to the taxation of capital gains

New Zealand's income tax law is founded on a distinction between ‘revenue' gains and expenditure, which are taxed and deductible and ‘capital' gains and expenditure, which are not taxed and non-deductible.

In principle, gains derived in the ordinary course of carrying on a business - or with the intention of making a gain - are income and are taxable. Other non-systematic gains are generally not taxed. In practice, however, it is often difficult to draw this distinction, because the particular rules require judgements about a person's intentions, the nature of their business and the role of a particular asset, liability or payment within that business.

10. As the following section elaborates, the current treatment of capital gains reduces the progressivity of the tax system.

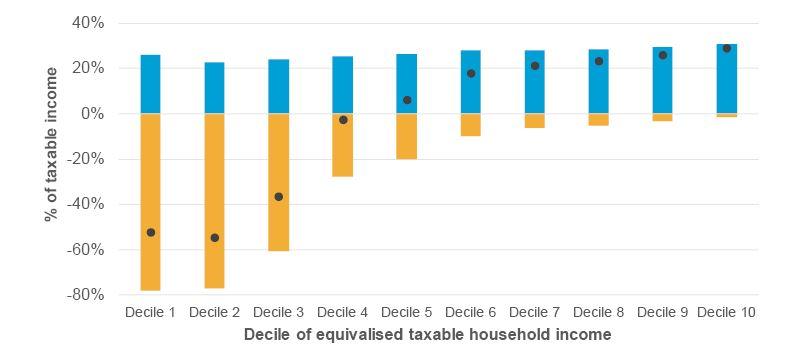

Distributional outcomes

11. Overall, relative to other OECD countries, the tax system is not particularly progressive. Figure 3.2 illustrates this point by showing tax and transfers as a percentage of taxable income. This figure shows that there is not a significant increase in average effective tax rates across taxable income deciles, even though the amount of tax paid increases by decile. The average rate of income tax paid by households ranges from 23% for lower income households, to 31% for higher-income households. Progressivity is instead largely delivered through transfers, such as Working for Families.

12. It is also important to note that the inequality-reducing power of the tax and transfer system has fallen over the last three decades (Nolan 2018, Perry 2017). This outcome reflects the fact that the tax system and the transfer system have both become less effective at reducing inequality.

Figure 3.2: Taxes and transfers, by income decile (2012/13)

Note: Taxable income excludes, by definition, untaxed capital gains. Tax is calculated for the purpose of this figure as the sum of income tax, GST and Accident Compensation Corporation (ACC) levies. Estimated using the Treasury's model of the tax and welfare system and Household Economic Survey 2012/13 data.

Source: The Treasury

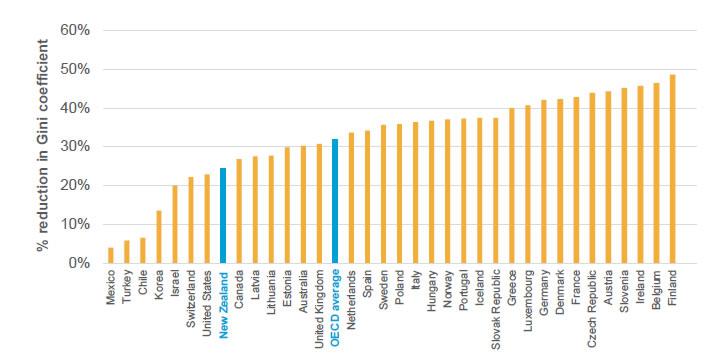

13. It is difficult to compare distributional outcomes across countries, because the results will be affected by the features of each economy, as well as choices about which taxes are included in the analysis. According to the OECD, however, New Zealand's tax and transfer system reduces income inequality by less than is the case in Australia or, on average, across OECD countries (see figure 3.3).

Problems, challenges and opportunities

14. The outcomes generated by the tax system reflect deep structural choices about what is taxed and what is not taxed. Two issues have been particularly prominent in the Group's discussions over the past year: the treatment of capital gains and the treatment of stocks of natural capital. In the Group's view, these structural choices have significant impacts on the fairness and balance of the tax system as a whole.

The treatment of capital gains

15. The current treatment of capital gains creates a set of interlinked problems.

Equity and fairness

16. A sense of fairness is central to maintaining public trust and confidence in the tax system. This is because a system that distributes the costs of taxation in a way that is perceived to be unfair will generate resentment and undermine social capital.

17. The inconsistent taxation of capital gains is unfair. It means that people earning the same amount of income can face quite different tax obligations, depending on whether their income is earned as capital gains or, say, as wages.

Figure 3.3: Reduction in income inequality on account of the tax and transfer system across OECD countries (2014/15)

Note: Estimated as the percentage difference in the Gini coefficient of income inequality before and after taxes and transfers. This figure is based on the OECD Income Distribution database. It includes personal income taxes, employees' social security contributions and cash transfers but excludes payroll taxes and value-added taxes such as GST.

Source: OECD

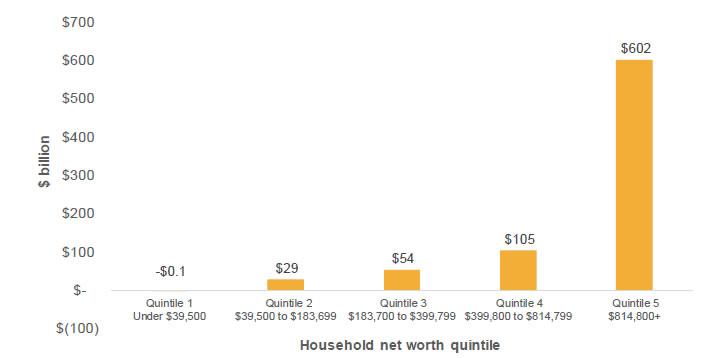

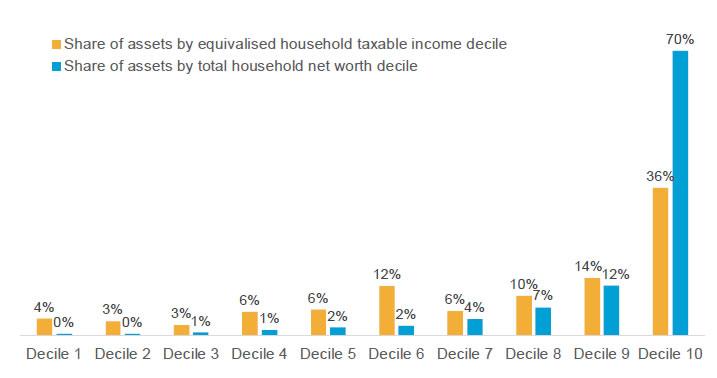

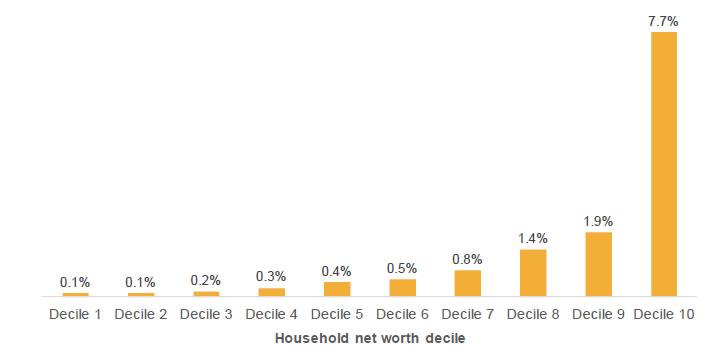

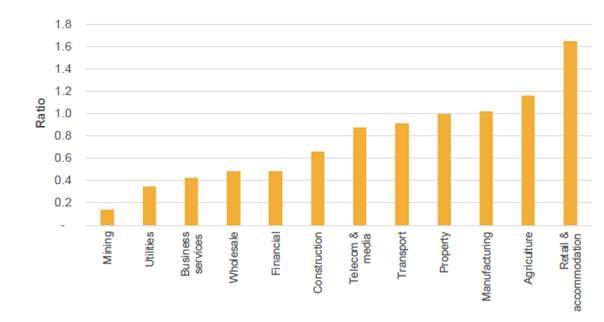

18. The resulting outcomes are also regressive. The distribution of net wealth is concentrated in the top 20% of households (see figure 3.4) and is even more concentrated when owner-occupied housing is excluded. This indicates that the distribution of untaxed capital gains is also likely to be quite skewed. Evidence from countries with capital gains taxes indicates that high-income people derive a much greater share of their income from capital gains than low- and middle-income people.

How does the treatment of capital gains affect our tax obligations?

Example 1

This year, Oliver earned $50,000 in wages. He will pay $8,020 in tax on this income.

Judy, on the other hand, earned $25,000 of taxable income from part-time work. She also sells shares in a business and received a non-taxable capital gain of $25,000. Judy has also earned $50,000 but under current law, Judy will pay $3,395 in tax.

Example 2

Paul earns a salary that roughly corresponds to the median New Zealand wage. Over the last ten years, he has earned about $450,000 of income from his job. He has paid tax of approximately $70,000 on that income.

Paul's friend Art purchased some residential property 10 years ago. He has been managing the property on a break-even basis by renting it to tenants and claiming deductions for maintenance, mortgage payments and rates.

Art recently sold this property, making a gain of $195,000. (This gain roughly corresponds to the difference in median New Zealand house prices across the 10-year period.) He is not subject to any tax on this gain under current tax rules, as the gain is of a capital nature.

19. The inconsistent taxation of capital gains therefore has the effect of reducing the proportion of tax paid by the wealthiest members of our society.

Figure 3.4: Total net worth (excluding owner-occupied housing), by net worth quintile (2015)

Note: Net worth estimates exclude owner-occupied housing. Quintiles are based on household net worth including owner-occupied housing.

Source: Stats NZ (Household Economic Survey 2015)

20. The Group is concerned that the resulting perceptions of unfairness will erode public acceptance of the prevailing levels of taxation, as well as the spirit of voluntary compliance that underpins efficient tax collection.

Integrity

21. The current approach reduces the integrity of the tax system because it creates opportunities and incentives for tax minimisation and avoidance. Taxpayers have a strong incentive, for example, to argue that their gains are on capital account and are therefore not taxable.

22. Other tax minimisation strategies - such as dividend avoidance - also take advantage of the inconsistent taxation of capital gains. These types of integrity risks sharpen perceptions of unfairness and further erode social capital.

23. It is often difficult to establish the boundary between capital gains and ordinary income. For example, take a person who spends a couple of months renovating a residential investment property and then sells the property for a substantial gain. A large portion of the gain will reflect the return on the person's labour. In the current system, however, it is likely to be treated as an untaxed capital gain.

24. In the case of certain sales of assets, the administration of the tax system is hampered by the need for subjective tests to assess the purpose or intention of those sales. These tests can create uncertainty for taxpayers when attempting to determine their tax obligations. Little revenue is collected, even with a bright line rule. This may also reflect problems with enforcement.

Fiscal adequacy and sustainability over time

25. As the population ages, a greater proportion will live off capital income in retirement. Together with the impact of technological change, this is likely to increase the capital intensiveness of the economy and the ratio of capital income to labour income.

26. A tax system that is more sustainable over time - and that is fair in an intergenerational sense - will need to draw much more upon capital income in the future. Capital gains can be an important component of this income.

27. A broader tax base would also provide more flexibility to respond to future challenges. At present, the gap between the company rate and the top personal rate is small but there are still integrity problems, with people using company structures and tax-free gains to lower their effective tax rates. These pressures will only grow if the company rate is lowered or the top personal rate is raised in the future.