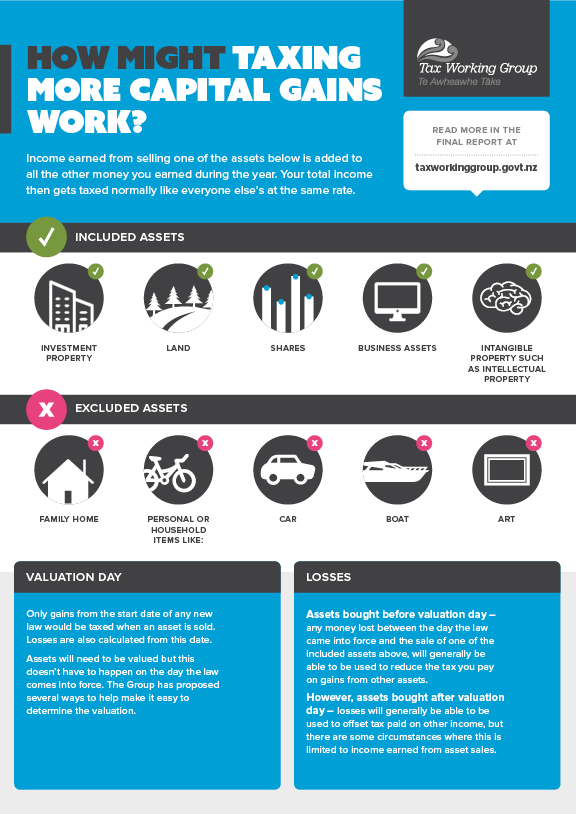

A tax on more capital gains would be applied differently depending on the asset.

Here are some examples of how the Group’s proposals would work with property, shares and managed funds.

View transcript

The Tax Working Group has a proposal to tax more capital gains, but how might this work?

If you make a gain selling one of these assets, it will be added to your income for the year. Your total income then gets taxed normally like everyone else’s.

It works a little differently for each asset.

Let’s look at property. Mary owns a few rental properties. She bought one for $500,000 in 2017, and sells it for $800,000 in 2023. On 1 April 2021, the new tax rules come into force and Mary decides to accept the next Council Valuation of $700,000 as the value of her house.

Mary won’t be taxed on $200,000 gain that occurred before 2021. It’s only the $100,000 gain after 1 April 2021 that matters.

Mary spent $70,000 on renovations ahead of the sale so her net gain is $30,000. Mary doesn’t earn any wages, but she receives $60,000 each year from her rental income.

So how much tax does Mary need to pay in 2023 when she sells the property? Under the current rules, Mary is only taxed on her $60,000 of rental income, and not the $30,000 she gets from selling the property, meaning she pays $11,020 in tax. Under the new rules, Mary would be taxed on $90,000 of income, because her net gain from selling her property is included. This means she pays $20,620 in tax. This is exactly the same amount of tax paid by someone who earns $90,000 a year in wages.

How about shares? Wiremu bought some shares for $40,000 after the new rules had been introduced. A few years later, he sold them for $50,000. That’s a capital gain of $10,000. Wiremu also earns $48,000 in wages, so his total income in the year he sold the shares is $58,000. Wiremu’s employer would have already sorted the tax on his wages, paying $7,420 to Inland Revenue. At today’s rates, his extra $10,000 would be taxed at 30%. Wiremu will have $3,000 more tax to pay because of the gain from the shares. He’ll pay exactly the same as someone who earned $58,000 just in wages.

Managed funds, like KiwiSaver, would work a bit differently. Your Fund Manager would pay any tax on the gains from your account each year, according to the tax rate you had selected. For example, if the value of your Australian and New Zealand shares in your KiwiSaver increased by $1,000, and your tax rate for KiwiSaver was 28%, your Fund Manager would pay $280 from your account to Inland Revenue. If your KiwiSaver lost that amount during the year, then you would get $280 back from Inland Revenue.

The Tax Working Group has recommended some reductions to KiwiSaver taxes to ensure that low- and middle-income New Zealanders are better off overall.